A collector had a house full of horrible things. “Do you like these?” Cocteau finally asked. “No. But my parents missed the chance of buying the impressionists cheap because they didn't like them. I buy only what I don't like.” A young Netherlander, said Cocteau, was the first to buy the impressionists and take them home. Locked in an insane asylum for fifteen years, he died there. In his trunk were found some of the masterpieces of impressionism, which had by then acquired considerable value. His parents went to the head of the asylum and accused him of having kept a sane man incarcerated.

Cocteau's vivacity of intelligence caused him to live in a world of accelerated images, as if a film were run in fast motion. One thinks of a different time stage as a real possibility: differing human beings apparently all on the same physical ground living actually at different accelerations. In Cocteau's case, there was no doubt that a rapidity of intelligence accounted for the multiplication, juxtaposition, proliferation, and mixing of experience and its exterior face, behavior—as well as for what was often called a certain superficiality or légèreté. “He who sees further renders less of what he sees, however much he renders.”

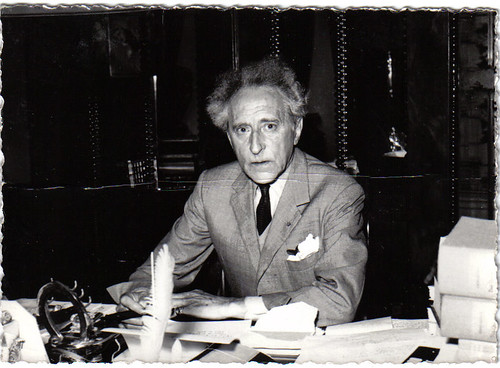

First met on the set of Le Testament d’Orphée in 1959 among the lime rocks, tortured as they are into Cocteauan shapes by the wind, at Les Baux in Provence—significantly on the day he filmed the death of the poet, himself—Cocteau treated the interviewer to a glimpse into a life that bridges two epochs (Proust and Rostand to Picasso and Stravinsky). He chatted with eminent grace between takes, then went over to stretch out again (upon a tarpaulin laid down out of camera range) on the floor of the quarried-out cavern in rock, lit up eerily by the floodlights, to be the transpierced poet—a spear through his breast (actually built around his breast on an iron hoop under his jacket). The hands gripped the spear; the talc-white face from the age of Diderot became anguished.

The taped interview took place in the Riviera villa of Mme. Alec Weisweiller a few months before Cocteau's death in the fall of 1963. The villa entrance was framed by facsimiles of two great Etruscan masks from his staging of his Oedipus Rex—a kind of static opera in scenes which he wrote after music by Stravinsky—masks worked in mosaic into the cement walk that winds through gardenia bushes and lilies to the portal out on the point of Cap Ferrat. You saw the schooner-form yacht of Niarchos out on the water toward Villefranche, where Cocteau lived in the Hotel Welcome in 1925 with Christian Bérard and wrote Orphée; the poet was framed by his own tapestry of Judith and Holofernes, which covers the whole of one of Mme. Weisweiller's dining terrace walls, and provokes strange reminiscences of the slumbering Roman soldiery in the “Resurrection” of Piero della Francesca. Lunch was preceded by a cocktail, mixed by the famous hands, which Cocteau said he had learned to make from a novel by Peter Cheyney: “white rum, curaçao, and some other things.” Lunch finished, the recorder was plugged in.

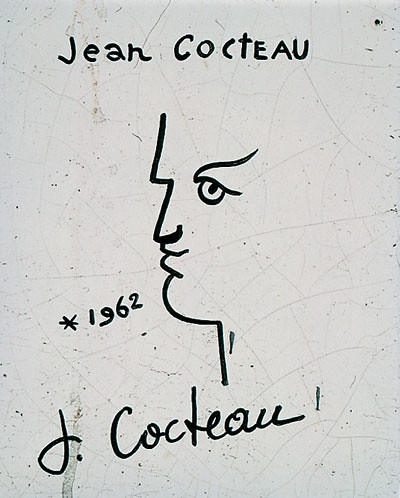

JEAN COCTEAU

After you have written a thing and you reread it, there is always the

temptation to fix it up, to improve it, to remove its poison, blunt its

sting. No—a writer prefers, usually, in his work the resemblances—how it accords with what he has read. His originality—himself—is not there, of course.

INTERVIEWER

When I brought forward your resemblance to Voltaire at lunch you

were—I had better say “highly displeased.” But you share Voltaire's

rapidity of thought.

COCTEAU

I am very French—like him. Very, very French.

INTERVIEWER

My thought was Voltaire isn't as dry-sharp as is supposed: that this

is a miscalculation owing to imputing to him what would be a thought-out

hypercleverness in a more lethargic mind. But in fact Voltaire wrote

very fast—Candide in three days. That holocaust of sparks was

simply thrown off. Whether or not this is true of Voltaire, it is

certainly true of you.

COCTEAU

Tiens! I am the antipode of Voltaire! He is all thought—intellect. I am nothing—“another” speaks in me. This force takes the form of intelligence, and this is my tragedy—and it always has been from the beginning.

INTERVIEWER

It takes us rather far to think you are victimized by

intelligence, especially since for a half century you have been thought

of as one of the keenest critical and critical-poetical intelligences in

France; but doesn't this bear on something you told me about yourself

and Proust—that you both got started wrong?

COCTEAU

We both came out of the dandyism of the end of the nineteenth

century. I turned my vest, eventually, toward 1912, but in the proper

sense—in the right direction. Yet I am afraid the taint has persisted

even to today. I suppressed all my earlier books of poems—from before

1913—and they are not in my collected works. Though I suppose that,

after all, something from that epoch has always . . .Marcel combated those things in his own way. He would circle among his victims collecting his “black honey,” his miel noir—he asked me once, “I beg of you, Jean, since you live in the rue d'Anjou in the same building with Mme. de Chevigné, of whom I've made the Duchesse de Guermantes; I entreat you to get her to read my book. She won't read me; and she says she stubs her foot in my sentences. I beg you—” I told him that was as if he asked an ant to read Fabre. You don't ask an insect to read entomology.

INTERVIEWER

Strictly statistically, you were born in 1889. How could it have

happened that you entered into this child-protégé phase, so very like

Voltaire, taken up by all Paris? Did you have some roots in the arts—in

your family, for example?

COCTEAU

No. We lived at Maisons-Laffitte, a few miles outside Paris; played

tennis at this house and that, and were divided into two camps over the

Dreyfus affair. My father painted a little, an amateur—my grandfather

had collected Stradivari and some excellent paintings.

INTERVIEWER

Excuse me. Do you think the loss of your father in your first year

bears on your accomplishment? There is a whole theory that genius is

only-childism, and you were brought up by women, by your mother. An

exceedingly beautiful one, from her pictures.

COCTEAU

I can only reply to that that I have never felt any connection with

my family. There is—I must say simply—something in me that is not in my

family. That was not visible in my father or mother. I do not know its

origin.

INTERVIEWER

What happened in those days after you were launched?

COCTEAU

I had met Edouard de Max, the theater manager and actor, and Sarah

Bernhardt, and others then called the “sacred monsters” of Paris, and in

1908 de Max and Bernhardt hired the Théâtre Fémina in the

Champs-Élysées for an evening of reading of my poems.

INTERVIEWER

How old were you then?

COCTEAU

Eighteen. It was the fourth of April, 1908. I became nineteen three

months later. I then came to know Proust, the Comtesse de Noailles, the

Rostands. The next year, with Maurice Rostand, I became director of the

deluxe magazine Schéhérazade.

INTERVIEWER

Sarah Bernhardt. Edmond—the Rostand who wrote Cyrano. It seems like another century. Then?

COCTEAU

I was on a slope that led straight toward the Académie Française

(where, incidentally, I have finally arrived; but for inverse reasons);

and then, at about that time, I met Gide. I was pleasing myself by

tracing arabesques; I took my youth for audacity and mistook witticism

for profundity. But something from Gide, not very clearly then, made me

ashamed.

INTERVIEWER

I recall something particularly scintillating you wrote in your first novel, Potamak,

begun in 1914—though I think you didn't finish and publish it until

after the war—which must have been ironically autobiographical of that

stage.

COCTEAU

Yes, Potomak was published in 1919 and 1924.

INTERVIEWER

You wrote something to the effect of: a chameleon has a master who

places it on a Scotch plaid. It is first frenzied, and then dies of

fatigue.

COCTEAU

C'était malheureusement comme ça! Yes, I thought literature

gay and amusing. But the Ballets Russes had come to Paris; had had to

leave Russia, I believe. There are these strange conjunctures. I often

wonder if much would have eventuated if Diaghilev had not come to Paris.

He would say, “I do not like Paris. But if it were not for Paris, I

believe I would not be staged.” Everything began, finally, you see, with

Stravinsky's Sacre. The Sacre du Printemps reversed everything. Suddenly, we saw that art was a terrible sacerdoce—the

Muses could have frightful aspects, as if they were she-devils. One had

to enter into art as one went into monastic orders; little it mattered

if one pleased or not, the point wasn't in that. Ha! Nijinsky. He was a

simple, you know; not in the least intelligent, and rather stupid. His

body knew; his limbs had the intelligence. He, too, was infected by

something happening then—when was it? It must have been in the May or

April of 1913. Nijinsky was taller than the ordinary, with a Mongol

monkey face, and blunted fingers that looked like they'd been cut off

short; it seemed unbelievable he was the idol of the public. When he

invented his famous leap—in Le Spectre de la Rose—and sailed

off the scene—Dimitri, his valet, would spew water from his lips into

his face, and they would engulf him in hot towels. Poor fellow, he could

not comprehend when the public hissed the choreography of Sacre du Printemps when he had himself—poor devil—seen they applauded Le Spectre de la Rose.

Yet he was—manikin of a total professional deformation that he

was—caught in the strange thing that was happening. Put the foot there; simply because it had always been put somewhere else before. I recall the night after the première of Sacre—Diaghilev,

Nijinsky, Stravinsky, and I went for a drive in a fiacre in the Bois de

Boulogne, and that was when the first idea of Parade was born.

INTERVIEWER

But it wasn't presented then?

COCTEAU

A year or two later, listening to music of Satie, it took further

form in my mind. Then, in 1917, to Satie's music, Léonide Massine, who

did the choreography, I who wrote it, Diaghilev, and Picasso—in

Rome—worked it out.

INTERVIEWER

Picasso?

COCTEAU

I had induced him to try set designs; he did the stage settings: the

housefronts of Paris, a Sunday. It was put on by the Ballets Russes in

Paris; and we were hissed and hooted. Fortunately, Apollinaire was back

from the front and in uniform, and it was 1917, and so he saved Picasso

and me from the crowd, or I am afraid we might have been hurt. It was

new, you see—not what was expected.

INTERVIEWER

Aren't you really positing a kind of passion of anticonformism in the ferment of those days?

COCTEAU

Yes. That's right. It was Satie who said, later, the great thing is

not to refuse the Legion of Honor—the great thing is not to have

deserved it. Everything was turning about. All the old traditional order

was reversing. Satie said Ravel may have refused the Legion of Honor

but that all his work accepted it! If you receive academic honors you

must do so with lowered head—as punishment. You have disclosed yourself;

you have committed a fault.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think this liberty can go too far?

COCTEAU

There is a total rupture between the artist and public since about

1914. But it will cause its opposite, of necessity, and there will be a

new conformism. The new great painter will be a figurative—but with

something mysterious. Undoubtedly, Marcel—Proust—was stronger because he

hid his crimes (and he lived those crimes) behind an apparent

classicism, not saying, “I am a nasty man of bad habits and I am going

frankly to recount them to you.”

INTERVIEWER

You make me think of Hemingway, in that. His whole school—

COCTEAU

He told me a very interesting thing. He said: “France is impossible.

The people are impossible. But you have luck. In America a writer is

considered a trained seal, a clown. But you respect artists so much here

that when you said, 'Careful; Genet is a genius,' when you said Genet

is a great writer he wasn't condemned; the judges took fright and let

him off.” And it is true, the thing Hemingway said. The French are

inattentive and the worst public in the world—yet the artist is still

respected. In America the theater audiences are very respectful, I am

afraid.

INTERVIEWER

Who would you name as fundamental to this conversion?

COCTEAU

Oh—Satie, Stravinsky, Picasso.

INTERVIEWER

If you had to name the chief architect of this revolt?

COCTEAU

Oh—for me—Stravinsky. But you see I met Picasso only in 1916. And of course he had painted the Demoiselles d'Avignon

nearly a decade before. And Satie was a great innovator. I can tell you

something about him that will perhaps seem only amusing. But it is very

significant. He had died, and we all went to his apartment, and under

his blotter on his desk we all found our letters to him—unopened.

INTERVIEWER

Some moments ago, you spoke of this “other.” I think we would do well

to try to pin down what you mean by that. Picasso has spoken of it—said

it is the real doer of his creation—and you have during our earlier

talks. How would you define it?

COCTEAU

I feel myself inhabited by a force or being—very little known to me. It gives the orders; I follow. The conception of my novel Les Enfants Terribles

came to me from a friend, from what he told me of a circle: a family

closed from societal life. I commenced to write: exactly seventeen pages

per day. It went well. I was pleased with it. Very. There was in the

original life story some connection with America, and I had something I

wanted to say about America. Poof! The being in me did not want to write

that! Dead halt. A month of stupid staring at paper unable to say anything. One day it commenced again in its own way.

INTERVIEWER

Do you mean the unconscious creates?

COCTEAU

I long said art is a marriage of the conscious and the unconscious.

Latterly, I have begun to think: Is genius an at-present undiscovered

form of the memory?

INTERVIEWER

Now bearing on that, you once wrote a long time ago that the idea is

born of the sentence as the dream of the positions of the dreamer. And

Picasso says a creation has to be an accident or fault or misstep, for

otherwise it has to come out of conscious experience, which is observed

from what preexists. And you've averred: the poet doesn't invent, he

listens.

COCTEAU

Yes, but it may be much more complex than that. There's Satie, who didn't want to receive outside messages. And to what do we listen?

INTERVIEWER

Simply, banally, how do you manage such things as names of characters?

COCTEAU

Dargelos, of course, was a real person. He is the one who throws the fatal snowball in The Blood of a Poet; again the same, a snowball, in my novel Les Enfants Terribles,

which Rosamond Lehmann has translated (with obsessive difficulty, she

wrote me); and this time, also, the black globule of poison—sent Paul to

provoke his suicide, I found I had to use the name of the actual

person, with whom I was in school. The name is mythical, but somehow it

had to remain that of the lad. There are strange things that enter into

these origins. Radiguet said to me: “In three days, I am going to be

shot by the soldiers of God.” And three days later he died. There was

that, too. The name of the Angel Heurtebise, in the book of poems L'Ange Heurtebise,

which was written in an unbroken automatism from start to finish, was

taken from the name of an elevator stop where I happened to pause once.

And I have named characters after designations on those great

old-fashioned glass jars in a pharmacy in Normandy.

INTERVIEWER

What about the mechanism of translation? I think you once wrote in German?

COCTEAU

I had a German nurse. Apart from a few

dozen words of yours, it is the only language I know aside from French.

But my vocabulary was very limited. From this handicap I extracted

obstacle—difficulty which I thought I could use to advantage, and I

wrote some poems in German. But that is another matter and touches on

the whole question of the necessity of obstacle.

INTERVIEWER

Well, what is this question of the necessity of obstacle?

COCTEAU

Without resistance you can do nothing.

INTERVIEWER

You were telling some story about the impressionists and a

Netherlander who bought them—which I think expressed one of your prime

convictions: about the mutability of taste or, really, the nonexistence

of bad-good in any real objective sense. And about that time I believe

you suggested poetry does not translate. Rilke—

COCTEAU

Yes, Rilke was translating my Orphée when he died. He wrote me that all poets speak a common language, but in different fashion. I am always badly translated.

INTERVIEWER

What I have read of your poetry in English does you no justice whatever.

COCTEAU

I write with an apparent simplicity—which is really a ferocious

mathematical calculation—the language and not the content. Which is to

say the after-the-fact work, for, regrettably, our vehicles of

communication in writing are conventions. If Picasso displaces an eye to

make a portrait jump into life or provoke collision, which gives the

sense of multiview, that is one thing; if I displace a word to restore

some of its freshness, that is a far, far more difficult thing.

Translators, mistaking my simplicity for insubstantiality, render me

superficial, I am told. Miss Rosamond Lehmann tells me I am badly

translated in English. Tiens, in German they thought to make my La Difficulté d'Être “the difficulty to Leben”; no! “the difficulty zu sein.” The difficulty to live is another thing: taxes, complications, and all the rest. But the difficulty to be—ah! to be here; to exist.

INTERVIEWER

Well, of course, if I may put in here, it seems you are writing a

language of considerable contraction out of a world in which there is a

very substantial amount of changing light and shade. You have got to say

a very great deal in a little space if you are to convey simultaneity.

You write somewhere that you mustn't look back (on your own product) for

“might you not turn into a column of sugar if you looked back?” It is

easy to take the surface of this joke; slide off. But it seems to me you

evoke facetedness, glint, crystallization, perhaps even the cube,

because you were intimately connected with the origins of Cubism; I

don't want to go too far. I know from what you have told me that you do

not “work these things up”—they jump into your mind. What are you to do,

then? “De-apt” them? Make them less apt and water them down? But that

would be false. It is possible to think that here is a reaching

for more mysterious truths, truths that issue from juxtaposition, on

the part of a delicate and in its special way quite modest mind.

COCTEAU

Story, of course, translates very well. Shakespeare translates in part because of his high relief—the immense relief of the tale derived from chronicles ordinarily, which one may read as one might read Braille.

INTERVIEWER

But surely the world doesn't read Shakespeare for just a kind of Lamb's tales approximation?

COCTEAU

No. Truly. There is something else. Madame Colette once said to me one needn't read

the great poets, for they give off an atmosphere. It is truly very

strange, too, that we poets can read one another, as Rilke says. With a

friend to help with the words, I can read Shakespeare in English, but

not the newspaper.

INTERVIEWER

Your own definition of poetry seems relevant here. You have said

somewhere that when you love a piece of theater, others say it is not

theater but something else; and if you love a film, your friends say

that is not film but it is something else; and if you admire something

in sport, they say that is not sport but it is something else. And

finally you have arrived at realizing that that “something else” is

poetry.

COCTEAU

You see, you do not know what you do. It is not possible to do what one intends.

The mechanism is too subtle for that, too secret. Apollinaire set out

to duplicate Anatole France, his model, and failed magnificently. He

created a new poetry, small, but valid. Some do a very small thing, like

Apollinaire, and have a large reward, as he did finally; others, a

great thing, as did Max Jacob, who was the true poet of Cubism, and not

Apollinaire, and the result—one's gain and reputation—is minute.

Baudelaire writes much fabricated verse and then—tout à coup!—poetry.

INTERVIEWER

Isn't it the same in Shelley?

COCTEAU

Shelley. Keats. One single phrase, and the whole of the poem carried

into the sky! Or Rimbaud commences writing poetry right from the start,

and then simply gives it up because it is very evident the audience

doesn't care.

INTERVIEWER

Is that really true?

COCTEAU

Yours and mine is a dreadful métier, my friend. The public is never

pleased with what we do, wanting always a copy of what we have done. Why

do we write—above all, publish? I posed this to my friend Genet. “We do

it because some force unknown to the public and also to us pushes us

to,” he said. And that is very true. When you speak of these things to

one who works systematically—one such as Mauriac—they think you jest. Or

that you are lazy and use this as an excuse. Put yourself at a desk and

write! You are a writer, are you not? Voilà! I have tried this. What comes is no good. Never any good. Claudel at his desk from nine to twelve. It is unthinkable to work like that!

INTERVIEWER

Why, then, bother?

COCTEAU

When it goes well, the euphoria of such moments has been much the most intense and joyous of my life experience.

INTERVIEWER

What finally worked out between you and Gide? I read once in a French

critic that his work always tended to keep to the surface, but yours

plunged for the depths, with—sometimes—a considerable fracture of the

waves, as well as sounding.

COCTEAU

We commenced to dispute in the press toward 1919. Gide always wanted to be visible;

for me, the poet is invisible, one who walks naked with impunity. Gide

was the architect of his labyrinth, by which he negated the character of

poet.

INTERVIEWER

Do you keep a sort of abstract potential reader or viewer in mind when you work?

COCTEAU

You are always concentrated on the inner thing. The moment one

becomes aware of the crowd, performs for the crowd, it is spectacle. It

is fichu.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about inspiration?

COCTEAU

It is not inspiration; it is expiration. [The gaunt, fine hands on the thorax; evacuation of the chest; a great breathing out from himself]

INTERVIEWER

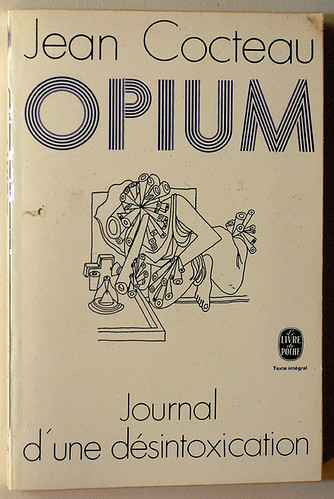

Are there any artificial helps—stimulants or drugs? You resorted to

opium after the death of Radiguet, wrote your book about it, Opium, and were, I believe, in a period of disintoxication from it when you wrote Les Enfants Terribles.

COCTEAU

It is very useful to have some depressant, perhaps. Extreme fatigue can serve. Filming Beauty and the Beast

on the Loire in 1945 immediately at the end of the war, I was very ill.

Everything went wrong. Electricity failures nearly every day; planes

passing over just at the moment of a scene. Jean Marais's horses made

difficulties, and he persisted in vaulting onto them himself out of

second-floor windows, refusing a double, and risking his bones. And the

sunlight changes every minute on the Loire. All these things contributed

to the virtue of the film. And in The Blood of a Poet Man

Ray's wife played a role; she had never acted. Her exhaustion and fear

paralyzed her and she passed before the cameras so stunned she

remembered nothing afterward. In the rushes we saw she was splendid;

with the outer part suppressed, she had been let perform.

INTERVIEWER

We have these great difficulties of communication in print. All our

readers are not John Gielgud or Louis Jouvet, and unfortunately when

they read a novel they must play the parts. How are we to get across the

shadings? I pose this because I know you have experimented with this

technical dilemma. I hope you will let me reproduce eight lines of your Le Cap de Bonne Espérance.

COCTEAU

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

I will not need to translate. That will not be the point.

Mon oeuvre encoche

et là

et là

et là [Sudden discovery.]

et là [Descent inward, with a note of

grief almost.]

dort

la profonde poésie.

Whatever else, I am sure few readers would supply that phrasing if your words were printed on a straight line.

COCTEAU

Very difficult.

INTERVIEWER

Rossellini, in Rome, told me that if he were to put down in a script

all his imagination casts up for the scene he would have to write a

novel; but in fiction we must put it down, or it is lost.

COCTEAU

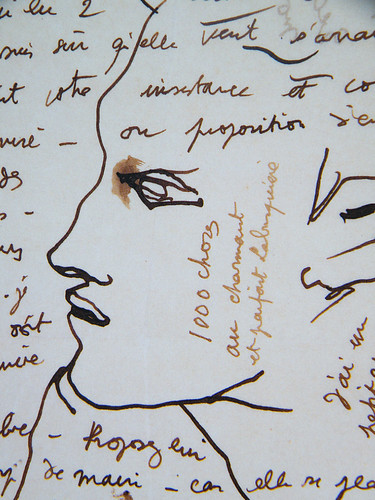

And the public is lazy! You ask them to enter into habits of thinking

other than their own, and they don't want to. And then . . . what you

have written in autograph changes in typewriting, and again in print.

Painting is more satisfying because it is more direct; you work directly

on the surface.

INTERVIEWER

We are struggling with imponderables here.

COCTEAU

But of course. The Cubists had to get rid of the whole question of subject, which is a thing,

to express the poetry—or art—which is a thing also. And that was the

meaning of Cubism, and not the accident that Matisse noticed the forms

were cubic.

INTERVIEWER

You are the greatest expositor of Pablo

Picasso, I should think very likely including Picasso. Your testimony is

invaluable because you have been with him side by side through the

whole art revolution from 1916 onward and because you have said his

principle of permanent revolution and refreshment in art is the chief

single influence in your own creative universe.

COCTEAU

He has no theory. He cannot have, because the creation ends at his wrists. Here. (Cocteau touches two beautiful, thin, coupled wrists, quite different from the costaud wrists of Picasso.) His mind does not enter in; there is an insulation, a defense, which he has formalized over years. It is the hand—la main de gloire—one

thinks of the sacred mummy hand capable of opening any door, but

severed at the wrist. An essential problem is that one cannot know,

questions of formulation and art are too complicated for it to be

possible for one to foresee, and one simply does not know.

Perhaps for this reason Picasso says of painting that it is the art of

the blind. He never reflects; never halts; makes no attempt to

concentrate his expression in a given work . . . to produce a chef-d'oeuvre. With him, nothing is superfluous and nothing is of capital importance.

INTERVIEWER

Could this be another way of saying that everything is of capital importance for the total oeuvre—but spread or diffused, not compacted—as in a da Vinci?

COCTEAU

He has done that once or twice. Formulated Guernica. And the Demoiselles d'Avignon—which

it must be recognized was the beginning of Picassan art, before which

there is no “Picasso” though there are Picassos. He finds first, and

afterwards researches. Not, as is sometimes said, surfacing that given

by intuition—but rather accommodating to the discoveries of his hand. It

is important to know that this puts one in constant flight from

oneself; from one's “experience.” Like Orpheus, Picasso pipes and the

objects fall in line after him, the most diverse, and submit to his

will. But what that will is—?

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if you recall what you wrote about him in 1923?

COCTEAU

If you would recall for me—

INTERVIEWER

You wrote: “He contents himself with painting, acquiring an

incomparable métier, and placing it at the service of hazard. I have

often seen Picasso seek to quit his muse—that's to say, attempt to paint

like everyone else. He quickly returns, eyes blindfolded . . .”

COCTEAU

Yes. One day in 1917—the year I induced him to attempt stage design; the settings for Parade—the company was on stage rehearsing when we noticed a vide—a

space—in the stage design. Picasso caught up a pot of ink and, with a

few strokes, instantly, caused lines to explode into Grecian columns—so

spontaneously, abruptly, and astonishingly that everyone applauded. I

asked him afterward, “Did you know beforehand what you were going to

do?” He said, “Yes and no. The unconscious must work without our knowing

it.” You see, art is a marriage of the conscious and the

unconscious. The artist must not interfere. Picasso, too, does not want

to be interfered with. When we were at dinner at D.C.'s the first

satellite passed over. “Ca m'emmerde,” he said—“That sullies

me. What has it to do with me?” He is wholly concentrated on his

work—more than any other man I know—inhumanly! He needs nothing outside

his own closed universe. He rebuffs his friends—but sees

nonentities—why? Because, he says, he does not want to nurture feelings

of resentment against those few he loves: who, alone, can disorient him.

He does not want to resent their intrusion—on the permanent gestation.

Yet—how strange it is that this art—so completely “closed,” that is,

personal and isolate—has the great popular success. It entirely

contradicts the shibboleth of the artist's contact with his audience.

INTERVIEWER

Is it possible to penetrate this closed universe and get his (undoubtedly partial and biased) opinion on him?

COCTEAU

He would tell you nothing! He never discusses the rationale. How can he, for it is a process of the hands—manual, plastic. He would reply with boutades,

jokes and absurdities: he lives behind them, in the protection of them,

as if they were quills of the hedgehog. His tremendous work—he works

more than any other man alive—is flight from the emptiness of life, and

from any kind of formalism of anything. Expressionism has gone on and on

knotting the cord—till it seems likely there is nothing left to knot

but the void. But if the Montparnasse revolution has come to its end

Picasso seems able to go on. Believe me—he does not know what to do

but he knows unerringly what not to do. His hand knows where not to go,

to avoid the stroke of the slightest banality, the least bit academic—a

constant renewal—but where it does go, where the line does go, is merely the only place left.

INTERVIEWER

Why does he deify the ugly? The effect on his psyche of the Spanish War?

COCTEAU

Do you know he made the first sketches in the direction of Guernica before the Spanish War? The real inspiration of Guernica was Goya.

INTERVIEWER

Even so, was Picasso turned to the late Goya by the Civil War? It

seems as if Picasso is transported “bodily” more than altered by an

influence, even if remaining in a frame of art reference.

COCTEAU

Art is but an extension of the life process for him, not

differentiated. Buffet criticized him publicly, and when he was asked to

retort by judging Buffet's art he said, “I do not look at his art. I do

not like the way he lives.” When he had been particularly heartless and

inaccessible in a human situation, I confronted him with it. “I am as I

paint,” he said. Tiens, mon ami, it takes great courage to be original! The first time a thing appears it disconcerts everyone, the artist too. But you have to leave it—not retouch it. Of course you must then canonize the “bad.” For the good is the familiar. The new arrives only by mischance. As Picasso says, it is a fault. And by sanctifying our faults we create. “It is too easy when you have a certain proficiency to be right,” he says.

INTERVIEWER

Does Picasso consciously try to displease—reserve to himself the right to displease like his torero friend Luis Miguel Dominguín? You told me how pleasant the original sketches for his chapel of La Guerre et La Paix

were, and how he progressively deformed them until we have the final

work—which is pretty frightening—and which you tell me made Matisse so

terrified of being caught at producing conventional beauty that he

deformed his chapel at Vence.

COCTEAU

He thinks neither of pleasing nor displeasing. He doesn't think of that at all.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of the French new-novelists who are beginning to abandon subject—Robbe-Grillet? Nathalie Sarraute?

COCTEAU

I must make a disagreeable confession. I read nothing within the

lines of my work. I find it very disconcerting; I disorient “the other.”

I have not looked at a newspaper in twenty years; if one is brought

into the room, I flee. This is not because I am indifferent but because

one cannot follow every road. And nevertheless such a thing as the

tragedy of Algeria undoubtedly enters into one's work, doubtless plays

its role in the fatigued and useless state in which you find me. Not

that “I do not wish to lose Algeria!” but the useless killing, killing

for the sake of killing. In fear of the police, men keep to a certain

conduct; but when they become the police they are terrible. No, one

feels shame at being a part of the human race. About novels: I read

detective fiction, espionage, science fiction.

INTERVIEWER

Do you recommend, then, to writers they read nothing serious at all?

COCTEAU [shrugs]

I myself do not.

INTERVIEWER [a few moments later]

To get back to that about Algeria, and so on—as a point of

clarification—I gather you mean the writer can't escape his world but

oughtn't to let his detail memory be too much interfered with? [And here Cocteau did something odd. He stood—rather tiredly—he was very slight, quite small—his photographs belie and do not really convey him; Picasso, for one, is wholly portrayed by his photos and if you have seen them you know him—and he went with slow steps to an end table. And he took up a tube of silver cardboard or foil, which made a cylinder mirror upon its outside. And he placed it down carefully in the exact center of an indecipherable photograph which was spread flat on this table, that I would learn was Rubens's “Crucifixion” taken with a camera that shot in round. Masses of fog blurred out in the photo; elongations without sense. Upon the tube, which corresponded in some unseen fashion with the camera, the maker, the photograph was restored —swirls became men. Nevertheless, the objective photograph remained insane.

He didn't say anything. Later on, he did remark, seated wearily, “I feel sorry for the young. It is not at all as it was in the Paris of ‘16. Paris has become an automobile garage. Neon, jazz—condition everything. And it is not at all as it was, a young man sitting writing by a candle. In Montparnasse, we never thought of a 'public.' It was all between ourselves. A great scientist came here the other day; he said, 'There is almost nothing left to be discovered.' And we know nothing about the mind! Nothing! Yevtushenko came to me. We had absolutely nothing to say to each other. Do you know why? There were twenty or thirty photographers and journalists there to snap and misrepresent it all. And the young are in a limbo that hasn't a future. Their auto accidents—to express their sense of the shortness of tenure. The world is very tired; we go back to the Charleston, the clothes of the twenties. And speleology—that is a rage here—burrowing down to the most primitive caves.”]

INTERVIEWER

You wrote one of your novels in three weeks; one of your theater

pieces in a single night. What does this tell us about the act of

composition?

COCTEAU

If the force functions, it goes well. If not, you are helpless.

INTERVIEWER

Is there no way to get it started, crank it up?

COCTEAU

In painting, yes. By application to all the mechanical details one

commences to begin. For writing, “one receives an order . . ..”

INTERVIEWER

Françoise Sagan—others—describe how writing begins to flow with the

use of the pen. I thought this was rather general experience.

COCTEAU

If the ideas come, one must hurry to set them down out of fear of

forgetting them. They come once; once only. On the other hand, if I am

obliged to do some little task—such as writing a preface or notice—the

labor to give the appearance of easiness to the few lines is

excruciating. I have no facility whatever. Yes, in one respect what you

say is true. I had written a novel, then fallen silent. And the editors

at the publishing house of Stock, seeing this, said, You have too great a

fear of not writing a masterpiece. Write something, anything. Merely to

begin. So I did—and wrote the first lines of Les Enfants Terribles.

But that is only for beginnings—in fiction. I have never written unless

deeply moved about something. The one exception is my play La Machine à Écrire. I had written the play Les Parents Terribles and it was very successful, and something was wanted to follow. La Machine à Écríre exists in several versions, which is very telling, and was an enormous

amount of work. It is no good at all. Of course, it is one of the most

popular of my works. If you make fifty designs and one or two please you

least, these will nearly surely be the ones most liked. No doubt

because they resemble something. People love to recognize, not venture.

The former is so much more comfortable and self-flattering.It seems to me nearly the whole of your work can be read as indirect spiritual autobiography.

INTERVIEWER

The wound in the hand of the poet in your film The Blood of a Poet—the

wound in the man's hand out of which the poetry speaks—certainly this

reproduces the “wound” of your experience in poetry around 1912-1914?

“The horse of Orpheus”—without which he remains terrestrial—is surely

that poetic and invisible “other” in you of which you speak.

COCTEAU

En effet! The work of every creator is autobiography, even

if he does not know it or wish it, even if his work is “abstract.” It is

why you cannot redo your work.

INTERVIEWER

Not rewrite? Is that absolutely precluded?

COCTEAU

Very superficially. Simply the syntax and orthography. And even there—My long poem—Requiem—has just come out from Gallimard. I leave repetitions, maladresses,

words badly placed quite unchanged, and there is no punctuation. It

would be artificial to impose punctuation on a black river of ink. A

hundred seventy pages—yes—and no punctuation. None. I was finishing

staging one of my things in Nice; I said to the leading woman, “When the

curtain is to come down, fall as if you had lost all your blood.” After

the première next night, I collapsed. And it was found I had

been unknowingly hemorrhaging within for days, and had almost no blood.

Hurrah!—my conscious self at lowest ebb, the being within me exults. I

commence to write—difficultly above my head in bed, with a stylo Bic,

as a fly walks on the ceiling. It took me three years to decipher the

script; I finally change nothing. One must fire on the target, after

all, as Stendhal does. What matter how it is said? I have told you I

dislike Pascal because I dislike his skepticism, but I like his style!

He repeats the same word five times in a sentence. What has Salammbô

to say to me? Nothing. Flaubert is simply bad. Montaigne is the best

writer in French. Simply out of the language, almost argot. Almost

slang. Straight out. It is so nearly always. [At this one point in the tape recording we have now reached, and as I remember only here, his voice loses its vibrant timbre—it “bleeds out.” His voice was exceptionally young; here it becomes faded. One feels sure he recognizes the imputations for the art of writing in the decision not to correct; I recall that if La Machine à Écríre was a disaster, clearly because it was intentional effort, then the successful Parents Terribles was dicté in a state of near somnambulism; there is the temptation to rerun the tape many times at this point, and ponder. That dicté—combined with “retouch nothing, not even orthography”—frightens; Picasso seen at firsthand too touches this terror; for it is certain that it is his line which writes, through all his later art, a living line, which he merely watches; a dilemma of the Montparnasse generation; one feels Cocteau has looked into this chasm inwardly many times, and that here is his courage.]

INTERVIEWER

By refaire, a moment ago, I think you did not quite mean “rewrite.”

COCTEAU [resignedly]

What is wanted is only what one has already done. Another Blood of a Poet . . . another Orphée

. . . It is not even possible. Picasso remarked the other day that the

bump on the bridge of my nose is that of my grandfather, but that I did

not have it when I was forty. My nose was straight. One changes, and is

not what one was.

INTERVIEWER

Radiguet?

COCTEAU

Oh, he was very young. There was an enormous creative liberation in

Paris. It was stopped—guillotined—by the Aristotelian rule of Cubism.

Radiguet was fifteen when he first appeared. His father was a

cartoonist, and Raymond used to bring in his work to deliver it to the

papers. If his father didn't produce, then Radiguet did the sketches

himself. One day, in the rue d'Anjou, the maid announced that there was

“a young man with a cane” downstairs. Raymond came up—he was fifteen—and

commenced to tell me all about art. We were his whole history, you see,

and he'd been used to lie on the bank of the Seine out of Paris and

read us. He had decided we were all wrong.

INTERVIEWER

How?

COCTEAU

He said that an avant-garde commences standing, and ends seated soon enough. He meant, in the academic chair.

INTERVIEWER

What did he propose?

COCTEAU

He said we should imitate the great classics. We would miss, and that

miss would be our originality. So later on he set out to imitate La Princesse de Clèves and wrote Le Bal du Comte d'Orgel, and I sought to imitate The Charterhouse of Parma and wrote Thomas l'Imposteur.

INTERVIEWER

How old was he when he wrote The Devil in the Flesh? One still sees that novel in so many of the bookshop windows of Paris.

COCTEAU

Oh, he was very young. He died at the end of his teens. That was—in

‘21—yes—two years before. He was remarkable in that he began perfectly

from the beginning, without error.

INTERVIEWER

How is that possible?

COCTEAU

Ah. Answer that! He slept on the floor or on a table from house to

house of the various painters. Then in the summer vacation with me on

the Bay of Arcachon he wrote The Devil in the Flesh; Bal du Comte d'Orgel

he did not even write, but sat and dictated to Georges Auric, who

tapped it out on the machine as they went. I looked on, and he simply

talked it all out. Rapidly and effortlessly. And it is flawless style.

He was a Chinese Mandarin with the naïveté of a child.

INTERVIEWER

Those were certainly very remarkable days. Modigliani. Yourself. Apollinaire.

COCTEAU

I will recount one thing; then you must let me rest. You perhaps know

the work of the painter Domergue? The long girls; calendar art, I am

afraid. He had a domestique in those days —a “housemaid” who

would make the beds, fill the coal scuttles. We all gathered in those

days at the Café Rotonde. And a little man with a bulging forehead and

black goatee would come there sometimes for a glass, and to hear us

talk. And to “look at the painters.” This was the “housemaid” of

Domergue, out of funds. We asked him once (he said nothing and merely

listened) what he did. He said he meant to overthrow the government of

Russia. We all laughed, because of course we did, too. That is the kind

of time it was! It was Lenin.

INTERVIEWER

Your position as by far the most celebrated literary figure in France

is crowned by the Académie Française, Belgian Royal Academy, Oxford honoris causa, and so on. Yet I suppose that these are “faults”?

COCTEAU

It is necessary always to oppose the avant-garde—if that is enthroned. Cocteau at dinner in Paris, a little restaurant in the Sixteenth arrondissement.

COCTEAU

Critics? A critic severely criticized my lighting at a Saturday

evening opening in Munich. I thanked him but there was no time to change

anything for the Sunday matinee. He felicitated me on the improvement.

“You see how my suggestions helped?” he said. No, there will always be a

conflict between creators and the technicians of the métier.

INTERVIEWER

I was struck by the banality of Alberto Moravia in an interview with a movie actress recently in the French press.

COCTEAU

I saw him on television and he was very mediocre. But that is the

difficulty. That is the kind of thing that goes down with the public.

And all they want are names.

COCTEAU

Appreciation of art is a moral erection; otherwise mere dilettantism. I believe sexuality is the basis of all friendship.

COCTEAU

This sickness, to express oneself. What is it? * Ball-point pen.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu