Gore Vidal, the elegant, acerbic all-around man of letters who presided with a certain relish over what he declared to be the end of American civilization, died on Tuesday at his home in the Hollywood Hills section of Los Angeles, where he moved in 2003, after years of living in Ravello, Italy. He was 86.

The cause was complications of pneumonia, his nephew Burr Steers said by telephone.

Mr. Vidal was, at the end of his life, an Augustan figure who believed himself to be the last of a breed, and he was probably right. Few American writers have been more versatile or gotten more mileage from their talent. He published some 25 novels, two memoirs and several volumes of stylish, magisterial essays. He also wrote plays, television dramas and screenplays. For a while he was even a contract writer at MGM. And he could always be counted on for a spur-of-the-moment aphorism, putdown or sharply worded critique of American foreign policy.

Perhaps more than any other American writer except Norman Mailer or Truman Capote, Mr. Vidal took great pleasure in being a public figure. He twice ran for office — in 1960, when he was the Democratic Congressional candidate for the 29th District in upstate New York, and in 1982, when he campaigned in California for a seat in the Senate — and though he lost both times, he often conducted himself as a sort of unelected shadow president. He once said, “There is not one human problem that could not be solved if people would simply do as I advise.”

Mr. Vidal was an occasional actor, appearing, for example, in animated form on “The Simpsons” and “Family Guy,” in the movie version of his own play “The Best Man,” and in the Tim Robbins movie “Bob Roberts,” in which he played an aging, epicene version of himself. He was a more than occasional guest on TV talk shows, where his poise, wit, looks and charm made him such a regular that Johnny Carson offered him a spot as a guest host of “The Tonight Show.”

Television was a natural medium for Mr. Vidal, who in person was often as cool and detached as he was in his prose. “Gore is a man without an unconscious,” his friend the Italian writer Italo Calvino once said. Mr. Vidal said of himself: “I’m exactly as I appear. There is no warm, lovable person inside. Beneath my cold exterior, once you break the ice, you find cold water.”

Mr. Vidal loved conspiracy theories of all sorts, especially the ones he imagined himself at the center of, and he was a famous feuder; he engaged in celebrated on-screen wrangles with Mailer, Capote and William F. Buckley Jr. Mr. Vidal did not lightly suffer fools — a category that for him comprised a vast swath of humanity, elected officials especially — and he was not a sentimentalist or a romantic. “Love is not my bag,” he said.

By the time he was 25, he had already had more than 1,000 sexual encounters with both men and women, he boasted in his memoir “Palimpsest.” Mr. Vidal tended toward what he called “same-sex sex,” but frequently declared that human beings were inherently bisexual, and that labels like gay (a term he particularly disliked) or straight were arbitrary and unhelpful. For 53 years, he had a live-in companion, Howard Austen, a former advertising executive, but the secret of their relationship, he often said, was that they did not sleep together.

Mr. Vidal sometimes claimed to be a populist — in theory, anyway — but he was not convincing as one. Both by temperament and by birth he was an aristocrat.

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal Jr. was born on Oct. 3, 1925, at the United States Military Academy at West Point, where his father, Eugene, had been an All-American football player and a track star and had returned as a flying instructor and assistant football coach. An aviation pioneer, Eugene Vidal Sr. went on to found three airlines, including one that became T.W.A. He was director of the Bureau of Air Commerce under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Mr. Vidal’s mother, Nina, was an actress and socialite and the daughter of Thomas Pryor Gore, the Democratic senator from Oklahoma.

Mr. Vidal, who once said he had grown up in “the House of Atreus,” detested his mother, whom he frequently described as a bullying, self-pitying alcoholic. She and Mr. Vidal’s father divorced in 1935, and she married Hugh D. Auchincloss, the stepfather of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis — a connection that Mr. Vidal never tired of bringing up. After her remarriage, Mr. Vidal lived with his mother at Merrywood, the Auchincloss family estate in Virginia, but his fondest memories were of the years the family spent at his maternal grandfather’s sprawling home in the Rock Creek Park neighborhood of Washington. He loved to read to his grandfather, who was blind, and sometimes accompanied him onto the Senate floor. Mr. Vidal’s lifelong interest in politics began to stir back then, and from his grandfather, an America Firster, he probably also inherited his unwavering isolationist beliefs.

Mr. Vidal attended St. Albans School in Washington, where he lopped off his Christian names and became simply Gore Vidal, which he considered more literary-sounding. Though he shunned sports himself, he formed an intense romantic and sexual friendship — the most important of his life, he later said — with Jimmie Trimble, one of the school’s best athletes. Trimble was his “ideal brother,” his “other half,” Mr. Vidal said, the only person with whom he ever felt wholeness. Jimmie’s premature death at Iwo Jima in World War II at once sealed off their relationship in a glow of A. E. Housman-like early perfection, and seemingly made it impossible for Mr. Vidal ever to feel the same way about anyone else.

After leaving St. Albans in 1939, Mr. Vidal spent a year at the Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico before enrolling at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. He published stories and poems in the Exeter literary magazine, but he was an indifferent student who excelled mostly at debating. A classmate, the writer John Knowles, later used him as the model for Brinker Hadley, the know-it-all conspiracy theorist in “A Separate Peace,” his Exeter-based novel.

Mr. Vidal graduated from Exeter at 17 — only by cheating, he later admitted, on virtually every math exam — and enlisted in the Army, where he became first mate on a freight supply ship in the Aleutian Islands. He began work on “Williwaw,” a novel set on a troopship and published in 1946 while Mr. Vidal was an associate editor at the publishing company E. P. Dutton, a job he soon gave up. Written in a pared-down, Hemingway-like style, “Williwaw” (the title is a meteorological term for a sudden wind out of the mountains) won some admiring reviews but gave little clue to the kind of writer Mr. Vidal would become. Neither did his second book, “In a Yellow Wood” (1947), about a brokerage clerk and his wartime Italian mistress, which Mr. Vidal later said was so bad, he couldn’t bear to reread it. He nevertheless became a glamorous young literary figure, pursued by Anaïs Nin and courted by Christopher Isherwood and Tennessee Williams.

In 1948 Mr. Vidal published “The City and the Pillar,” which was dedicated to J. T. (Jimmie Trimble). It is what we would now call a coming-out story, about a handsome, athletic young Virginia man who gradually discovers that he is homosexual. By today’s standards it is tame and discreet, but at the time it caused a scandal and was denounced as corrupt and pornographic. Mr. Vidal later claimed that the literary and critical establishment, The New York Times especially, had blacklisted him because of the book, and he may have been right. He had such trouble getting subsequent novels reviewed that he turned to writing mysteries under the pseudonym Edgar Box and then, for a time, gave up novel-writing altogether. To make a living he concentrated on writing for television, then for the stage and the movies.

Work was plentiful. He wrote for most of the shows that presented hourlong original dramas in the 1950s, including “Studio One,” “Philco Television Playhouse” and “Goodyear Playhouse.” He became so adept, he could knock off an adaptation in a weekend and an original play in a week or two. He turned “Visit to a Small Planet,” his 1955 television drama about an alien who comes to earth to study the art of war, into a successful Broadway play. His most successful play was “The Best Man,” about two contenders for the presidential nomination. It ran for 520 performances on Broadway before it, too, became a successful film, in 1964, with a cast headed by Henry Fonda and a screenplay by Mr. Vidal. It was revived on Broadway in 2000 and is now being revived there again as “Gore Vidal’s The Best Man.” Mr. Vidal’s reputation as a script doctor was such that in 1956 MGM hired him as a contract writer; among other projects he helped rewrite the screenplay of “Ben-Hur,” though he was denied an official credit. He also wrote the screenplay for the movie adaptation of his friend Tennessee Williams’s play “Suddenly, Last Summer.”

By the end of the ’50s, though, Mr. Vidal, at last financially secure, had wearied of Hollywood and turned to politics. He had purchased Edgewater, a Greek Revival mansion in Dutchess County, N.Y., and it became his headquarters for his 1960 run for Congress. He was encouraged by Eleanor Roosevelt, who had become a friend and adviser.

The 29th Congressional District was a Republican stronghold, and though Mr. Vidal, running as Eugene Gore on a platform that included taxing the wealthy, lost, he received more votes in running for the seat than any Democrat in 50 years. And he never tired of pointing out he did better in the district than the Democratic presidential candidate that year, John F. Kennedy.

In the ’60s Mr. Vidal also returned to writing novels and published three books in fairly quick succession: “Julian” (1964), “Washington, D.C.” (1967) and “Myra Breckinridge” (1968). “Julian,” which some critics still consider Mr. Vidal’s best, was a painstakingly researched historical novel about the fourth-century Roman emperor who tried to convert Christians back to paganism. (Mr. Vidal himself never had much use for religion, Christianity especially, which he once called “intrinsically funny.”) “Washington, D.C.” was a political novel set in the ’40s. “Myra Breckinridge,” Mr. Vidal’s own favorite among his books, was a campy black comedy about a male homosexual who has sexual reassignment surgery.

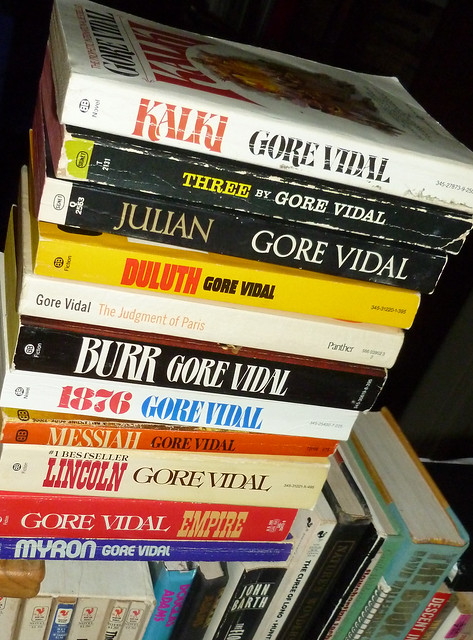

Perhaps without intending it, Mr. Vidal had set a pattern. In the years to come his greatest successes came with historical novels, especially what became known as his American Chronicles sextet: “Washington, D.C.,” “Burr” (1973), “1876” (1976), “Lincoln” (1984), “Hollywood” (1990) and “The Golden Age” (2000). He turned out to have a particular gift for this kind of writing. These novels were learned and scrupulously based on fact, but also witty and contemporary-feeling, full of gossip and shrewd asides. Harold Bloom wrote that Mr. Vidal’s imagination of American politics “is so powerful as to compel awe.” Writing in The Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt said, “Mr. Vidal gives us an interpretation of our early history that says in effect that all the old verities were never much to begin with.”

But Mr. Vidal also persisted in writing books like “Myron” (1974), a sequel to “Myra,” and “Live From Golgotha: The Gospel According to Gore Vidal” (1992), which were clearly meant as provocations. “Live From Golgotha,” for example, rewrites the Gospels, with Saint Paul as a huckster and pederast and Jesus a buffoon. John Rechy said of it in The Los Angeles Times Book Review, “If God exists and Jesus is His son, then Gore Vidal is going to Hell.”

In the opinion of many critics, though, Mr. Vidal’s ultimate reputation is apt to rest less on his novels than on his essays, many of them written for The New York Review of Books. His collection “The Second American Revolution” won the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism in 1982. About a later collection, “United States: Essays 1952-1992,” R. W. B. Lewis wrote in The New York Times Book Review that Vidal the essayist was “so good that we cannot do without him,” adding, “He is a treasure of state.”

Mr. Vidal’s essays were literary, resurrecting the works of forgotten writers like Dawn Powell and William Dean Howells, and also political, taking on issues like sexuality and cultural mores. The form suited him ideally: he could be learned, funny, stylish, show-offy and incisive all at once. Even Jason Epstein, Mr. Vidal’s longtime editor at Random House, once admitted that he preferred the essays to the novels, calling Mr. Vidal “an American version of Montaigne.”

“I always thought about Gore that he was not really a novelist,” Mr. Epstein wrote, “that he had too much ego to be a writer of fiction because he couldn’t subordinate himself to other people the way you have to as a novelist.”

Success did not mellow Mr. Vidal. In 1968, while covering the Democratic National Convention on television, he called William F. Buckley a “crypto-Nazi.” Buckley responded by calling Mr. Vidal a “queer,” and the two were in court for years. In a 1971 essay he compared Norman Mailer to Charles Manson, and a few months later Mailer head-butted him in the green room while the two were waiting to appear on the Dick Cavett show. They then took their quarrel on the air in a memorable exchange that ended with Mr. Cavett’s telling Mailer to take a piece of paper on the table in front of them and “fold it five ways and put it where the moon don’t shine.” In 1975 Mr. Vidal sued Truman Capote for libel after Capote wrote that Mr. Vidal had been thrown out of the Kennedy White House. Mr. Vidal won a grudging apology.

Some of his political positions were similarly quarrelsome and provocative. Mr. Vidal was an outspoken critic of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, and once called Norman Podhoretz, the editor of Commentary, and his wife, the journalist Midge Decter, “Israeli Fifth Columnists.” In the 1990s he wrote sympathetically about Timothy McVeigh, who was executed for the Oklahoma City bombing. And after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, he wrote an essay for Vanity Fair arguing that America had brought the attacks upon itself by maintaining imperialist foreign policies. In another essay, for The Independent, he compared the attacks to the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor, arguing that both Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and George W. Bush knew of them in advance and exploited them to advance their agendas.

As for literature, it was more or less over, he declared more than once, and he had reached a point where he no longer much cared. He became a sort of connoisseur of decline, in fact. America is “rotting away at a funereal pace,” he told The Times of London in 2009. “We’ll have a military dictatorship pretty soon, on the basis that nobody else can hold everything together.”

In 2003 Mr. Vidal and his companion, Mr. Austen, who was ill, left their cliffside Italian villa La Rondinaia (the Swallow’s Nest) on the Gulf of Salerno and moved to the Hollywood Hills to be closer to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Mr. Austen died that year, and in “Point to Point Navigation,” his second volume of memoirs, Mr. Vidal recalled that Mr. Austen asked from his deathbed, “Didn’t it go by awfully fast?”

“Of course it had,” Mr. Vidal wrote. “We had been too happy and the gods cannot bear the happiness of mortals.” Mr. Austen was buried in Washington in a plot Mr. Vidal had purchased in Rock Creek Cemetery. The gravestone was already inscribed with their names side by side.

After Mr. Austen’s death, Mr. Vidal lived alone in declining health himself. He was increasingly troubled by a knee injury he suffered in the war, and used a wheelchair to get around. In November 2009 he made a rare public appearance to attend the National Book Awards in New York, where he was given a lifetime achievement award. He evidently had not prepared any remarks, and instead delivered a long, meandering impromptu speech that was sometimes funny and sometimes a little hard to follow. At one point he even seemed to speak fondly of Buckley, his old nemesis. It sounded like a summing up.

“Such fun, such fun,” he said.

"I never miss a chance to have sex or appear on television."

"It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail."

"A narcissist is someone better looking than you are."

"Any American who is prepared to run for president should automatically by definition be disqualified from ever doing so."

"Democracy is supposed to give you the feeling of choice like, Painkiller X and Painkiller Y. But they're both just aspirin."

"Envy is the central fact of American life."

"Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little."

"The United States was founded by the brightest people in the country — and we haven't seen them since."

"Every four years the naive half who vote are encouraged to believe that if we can elect a really nice man or woman President everything will be all right. But it won't be."

"Andy Warhol is the only genius I've ever known with an IQ of 60"

"A good deed never goes unpunished."

"All children alarm their parents, if only because you are forever expecting to encounter yourself."

"Apparently, a democracy is a place where numerous elections are held at great cost without issues and with interchangeable candidates."

"Fifty percent of people won't vote, and fifty percent don't read newspapers. I hope it's the same fifty percent."

"Some writers take to drink, others take to audiences."

"The genius of our ruling class is that it has kept a majority of the people from ever questioning the inequity of a system where most people drudge along, paying heavy taxes for which they get nothing in return"

"Style is knowing who you are, what you want to say, and not giving a damn."

"The more money an American accumulates, the less interesting he becomes."

"The four most beautiful words in our common language: I told you so."

"Congress no longer declares war or makes budgets. So that's the end of the constitution as a working machine."

"We should stop going around babbling about how we're the greatest democracy on earth, when we're not even a democracy. We are a sort of militarised republic."

"As the age of television progresses the Reagans will be the rule, not

the exception. To be perfect for television is all a President has to

be these days."

"Sex is. There is nothing more to be done about it. Sex builds no roads, writes no novels and sex certainly gives no meaning to anything in life but itself."

"Think of the earth as a living organism that is being attacked by billions of bacteria whose numbers double every forty years. Either the host dies, or the virus dies, or both die."

"There is no such thing as a homosexual or a heterosexual person. There are only homo- or heterosexual acts. Most people are a mixture of impulses if not practices."

"There is no human problem which could not be solved if people would simply do as I advise."

Kevin RothsteinNew York

Verified

A great man and a true patriot who understood how the Founders were flawed men and not saints and who also tried to warn the people to beware the liars, hypocrites and scoundrels who profit off fear and ignorance.

He will never be replaced as there is no other writer with the possible exception of Chris Hedges who can articulate in so elegant a fashion the general sense of despair felt by so many on what remains of the left in America at our current decrepit condition, both physical and spiritual.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 7:53 a.m.RECOMMENDED103

MR BillBlue Ridge GA

A great writer, commenter, and patriot. He believed the NYTimes to be prejudiced against him (mostly over his sexuality) and would be gratified to find his death notice above the fold. (At least, electronically)>

I reread "Lincoln" after reading Keans-Goodwin's "A Team of Rivals", and it was refreshing to have a view of Lincoln as politician and poweruser that was not so reverent.

And somewhere he described the American Conservative movement as an attempt to create massive piles of tax exempt money by creating an plutocracy.

Greatly missed.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 7:43 a.m.RECOMMENDED103

samluduwilton, nyNYT Pick

Hitchens gone. Vidal gone.

The world is a lot less fun.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:45 a.m.RECOMMENDED102

ACWNew Jersey

Yes, and I expect Vidal would appreciate it if someone said anything even remotely as witty with regard to his passing. Unfortunately the art of invective on the right has descended to the level of the Coulters, O'Reilly's, Limbaughs, and Hannitys, who are mere schoolyard bullies.

In reply to IanAug. 1, 2012 at 8:28 a.m.RECOMMENDED93

Thomas MischlerCaledonia, MI

I will never forget watching Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley, Jr. commenting on one of the major political conventions in 1968. I was 16, and although I cannot recall which party's convention it was, I distinctly recall being fascinated with their back and forth banter. I ended up with a deep respect for both men's intellect - and a life long fascination with politics, history, and intellectualism.

Ah, those were the days, weren't they? When two men of opposing ideologies could sit in a room together, present their views in a respectful manner, shake hands at the end and leave the audience enriched, enlightened, and enthralled.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:29 a.m.RECOMMENDED76

ADNew York

One thing that's particularly sad about his death, as well as Christopher Hitchens' and even Bill Buckley's, is the sorry state of public discourse today and the anti-intellectual political and social climate that they've left behind.

Political and societal stupidity has always existed in some form or another, but rarely has it loomed so spectacularly over the broader culture in this country and rarely have the stupid, shallow and ignorant wielded as much power and influence as today.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 11:14 a.m.RECOMMENDED71

John NewtonSydney Australia

Ave atque vale Gore Vidal, a truly great American. Perhaps my favourite Vidalism was his response to a jejune question from a journalist as to whether he had first slept with a man or a woman. His response "I was too polite to ask" says much for the grace of the man

Aug. 1, 2012 at 7:56 a.m.RECOMMENDED68

richard.jasperOneonta, NY

Quite aside from the subject matter, this piece is an outstanding example of the art of obituary writing. Well done, Mr. McGrath, well done indeed!

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:06 a.m.RECOMMENDED66

Dileep GangolliEvanston, IL

"In a 1971 essay he compared Norman Mailer to Charles Manson, and a few months later Mailer head-butted him in the green room while the two were waiting to appear on the Dick Cavett show"

Gone are the days when authors were personalities that appeared on national broadcast talk shows. So sad.

Now we are stuck with Kardashians, Hiltons, and other drivel that is so meaningless.

Perhaps Vidal was correct, American civilization is in decline.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 8:59 a.m.RECOMMENDED66

donmintzTrumansburg, NY

Gore Vidal belonged to a breed, now with his death perhaps gone from American life forever: the gentleman scholar. The "gentleman" determined his elegant style, both its sounds and its wit. The "scholar" pertains not to degrees certifying to formal learning but to a taste for solid research, an inherent sense of fact and past opinion, a similarly inherent talent for turning this material into knowledge—and sometimes even into wisdom.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:43 a.m.RECOMMENDED60

Frank SchaefferSalisbury MANYT Pick

Back in the day in the 70s-80s when I was still living near Buckley in Switzerland he used to come over for tea with my late father (theologian Francis Schaeffer and a founder of the religious right). Buckley was talking to Dad and I about how Vidal and he used to fight on TV only to go have a drink together later. I often recall that conversation in the context of today's right/left divide wherein I don't picture any Fox News host having a drink with any MSNBC host after they've disagreed repeatedly and pointedly in public.

Buckley knew that a large measure of his reputation rested on his ability to at least match some of Vidal's arguments and larger than life personality. They were strangely matched mirror images of each other, privileged, educated, odd, arrogant and decent. And based on opposite presuppositions they both agreed that America was/is in decline.

Buckley seemed to be fond of Vidal and proud to have argued with him. When they argued I learned something. Today when our "pundits" spout all I learn is that they hate each other, or rather pretend to since dudgeon-for-profit sells TV advertising minutes.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 10:44 a.m.RECOMMENDED58

davwardnycNYT Pick

It's long been clear this was coming, but that doesn't make Gore Vidal's death any easier to take. Growing up gay in the deep south in the 90's, Gore became one of my icons: an incredibly erudite, largely self-taught writer/historian/essayist/wit who also happened to be gay, and unabashedly so. The first book of his I read was "Lincoln," strangely, but I quickly followed it with everything else. Even the weird ones (e.g. "Live From Golgotha") were entertaining, thought provoking reads. It is not overstating things to say that most of the threads of the 20th century are woven into his remarkable life.

I very rarely post comments on the web, either here or elsewhere, but I felt compelled to post this one just to say that although I never knew Gore Vidal, I feel like I did, and I will miss having his increasingly-irascible voice presiding over our noisy national dialogue.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 8:55 a.m.RECOMMENDED58

Kevin RothsteinNew York

Verified

I forgot to mention the time Vidal called William F. Buckley, Jr. a "crypto-fascist after the conservative icon suggested in a debate with him that we should "atomize" the North Vietnamese. Buckley was so flummoxed he could only respond with a gay slur. R.I.P. We will not see the likes of Mr. Vidal again.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 8:15 a.m.RECOMMENDED58

Donald Dal MasoNYC

When Buckley challenged Gore's claim that Nixon had an irresistable criminal efficiency in politics by noting that Nixon had lost the Gubernatorial race in California, Gore replied without a blink that the reason was "You can't fool all of the people all of the time, except on television."

I always felt there was a profound seriousness inside Gore, and that Bush/Cheney had really violated sense of decency and humanity that Gore ordinarily kept out of sight.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 7:58 a.m.RECOMMENDED52

A readerBrooklyn, NY

My favorite Vidal story took place during his boyhood in Washington, D.C., when he stayed with his grandfather Thomas Gore, the populist Democratic senator from Oklahoma (and, as Vidal said, the last senator from an oil state who left office without a personal fortune). In the early years of the Great Depression, 17,000 veterans of WWI set up a ramshackle "Hooverville" camp in front of the Capitol and demanded their "bonus." Vidal rode in the back of a car with his grandfather, and one of the protesting veterans threw a rock through the window. The rock landed on the floor between the Senator and the boy. Three years later Social Security was enacted, and Vidal came to believe that the creation of the safety-net was the only thing that kept America from revolution in hard times. Could a bloodbath like the French revolution happen here? Of course it could. "If the rich are too rich and the poor have nothing to support them in bad times," Vidal wrote, "then how is liberty’s tree to be nourished?"

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:25 a.m.RECOMMENDED47

MR BillBlue Ridge GANYT Pick

Try growing up gay in rural Western North Carolina in the 60's. I was 10 or so, a bookish child, who saw Mr. Vidal on the "Today" show (imagine having a public intellectual, much less a serious author on today's "Today"...) and told my mom I'd like to be like him.

I still remember her grim expression and the force with which she said "No, you certainly do not!"

In reply to davwardAug. 1, 2012 at 9:20 a.m.RECOMMENDED46

JessicaSewanee, TN

A cranky eccentric not afraid to speak truth (as he saw it) to power. We need people like Gore Vidal to open the windows on our claustrophobic self-absorption as a nation.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 8:59 a.m.RECOMMENDED45

phylum chordataearth

"I'm a born-again atheist." Thanks again Mr. Vidal, me too.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:43 a.m.RECOMMENDED42

PattyConnecticut

His commentary during this season's election will be sorely missed.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 7:42 a.m.RECOMMENDED42

William M. ShawShreveport, LA

Gore Vidal was a unique figure in America's politico-literary history, a writer who by virtue of his birth and connections was able to speak his mind freely without having to do obeisance to the sacred cows of our culture's group-speak. He will be sorely missed.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 7:53 a.m.RECOMMENDED40

WinthropThe flats of e'side Buffalo, NY

G.V. referred to virtually all politicians as 'bankerboys.' Upon reflection, it's hard to refute that assertion, even if you wanted too.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 8:59 a.m.RECOMMENDED39

TomLake WoebegoneNYT Pick

My guess is, by now, the brilliant Mr. Vidal has received his Grand Surprise that there is another life, and is being hosted at some elegant, heavenly dinner.

I'd love to hear his quip on how that happened, in spite of his Mensa level intelligence and cocksure judgments.

Lordy, that guy could write. How I miss the exchanges between him and Bill Buckley. It was redolent of Hyde Park and Shaw and Chesterton.

I do hope Bill is at the reception too and they are exchanging elegant barbs again.

I can imagine Buckley telling him, "Welcome, Gore! Now that you're here, the average IQ has gone down on Earth and up in Heaven. The same thing happened when I arrived here....but it was a much larger jump!"

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:27 a.m.RECOMMENDED38

Charles MichenerCleveland, OHNYT Pick

I knew Gore in Rome in the1990s. By then he had become an arrestingly corpulent version of his beautiful younger self whose vanity was distilled in his conversation. He was welcoming, alert and curious - and exhausting. Over dinner in a trattoria he was an unstoppable stream of pronouncements, name-dropping and sexual boasting ("See that waiter over there . . ."). He was outrageous, funny, and, as happens with all supreme narcissists, borderline boring. I loved being with him and couldn't wait to leave him. Underneath the grand performance he was also, I felt, immensely lonely. He may not have valued "love," as this excellent obituary reports, but he certainly needed and cherished friendship.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 10:50 a.m.RECOMMENDED37

JULIAN BARRYREDDING, CTNYT Pick

Some years ago I happened to find myself sitting next to Gore on a flight from New York to Los Angeles. I introduced myself and he recognized my name and was effusive in his praise of a play I'd had running on Broadway (Lenny). I made up my mind that the best possible way to treat this five hour journey was to keep my mouth shut and just listen to what he had to say, and Gore seemed quite content to go along with that idea. It was a wonderful five hours.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 1:10 p.m.RECOMMENDED36

rUS

I think Vidal would have lived another decade had he remained on the Amalfi coast.

Returning to the US was a mistake. This awful country finally killed him, as it is slowly strangling the rest of us.

Robert CoaneOrange County, NY

Wrong. Read the last three paragraphs and final line. I don't think you got there: “Such fun, such fun,” he said.

"Unloved," you say. “Didn’t it go by awfully fast?” is a declaration of love ... from a dying man, none-the-less.

Strong language and fierce opinion are often declared malcontent by the weak and hapless. We can always tear down heros to feel better about ourselves.

In reply to happyktAug. 1, 2012 at 8:50 a.m.RECOMMENDED34

Drogo52Houston TX

Watch the old TV clips of Vidal & Buckley going at each other with acerbity, intellectual brilliance & debate-team courtesy makes you fully appreciate how thoroughly Fox News and MSNBC have destroyed themeaningful discussion of political issues. We're lucky to still have Bill Moyers in the TV studio.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 10:49 a.m.RECOMMENDED33

DavidDes Moines, IowaNYT Pick

"Myra Breckinridge" was the first Vidal book I ever read. I knew nothing about it, other than having picked up a cheap pocket-paperback copy and that I thought I was going to be reading an overly-serious piece of literature. But it was nothing like I expected. So many playful scenes. Camp. Weird. Inspiring. Mercurial. Brilliant. Tons of aphorisms. ("Yet nothing human that is great can entirely end" -- using a scene from "Naughty Marietta" -- with actress Jeanette MacDonald as a poignant way to illustrate.) The book was as culturally ping-ponging as a Salman Rushdie book, and as inventive as Jean Genet -- tossing around and mixing sexual pronouns -- as if they were of little consequence. There's an extremely lengthy paragraph at the end that is so complex, so beautifully written, I had to come back to it to continually luxuriate in the words and thoughts. The sensory-overloaded paragraph starts with a hand resting between a woman's legs -- "the charneled lair, the last mystery, the maw of creation." Gorgeous.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:42 a.m.RECOMMENDED33

David StoneNew York, NYNYT Pick

In 1998 I wrote a novel about a secret society in the Navy. With no literary connections, I was at a loss about what to do next. The writers I most admired were Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams and Gore Vidal. Gore Vidal was the only one still alive, so I wrote to him and asked if he would read my novel.

I knew you could write a letter to a writer care of his or her publisher, not that I had ever done that before, but in Vidal’s case I actually knew his address. He lived in a villa in Ravello, Italy. I addressed my request to Gore Vidal, La Rondinaia, Ravello, Italy. I had no real expectation that a letter so vaguely addressed would reach him and, even if it did, that he would agree to read my book. Vidal was at the height of his fame and was, no doubt, constantly asked to review books by real published authors and to give them his imperial approval.

A blue airmail envelope promptly appeared in my mailbox with a very short note inside from Gore Vidal asking me to send the manuscript to him. Amazingly, he read my book as soon as he received it and wrote back to me that it was quite a story, with all sorts of reverberations, but predicted it was too hot for publishers. Just a few months ago, I finally published the novel Gore Vidal read and championed in 1998 (Trial of Honor: A Novel of a Court Martial). I dedicated it to Gore Vidal.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 1:02 p.m.RECOMMENDED32

DavidNew York

The term "liberal elite" is a meaningless insult developed by right wingers to slander all progressives and appeal to the poor and less well off to vote against their own economic interests. What is your term for all the billionaires like the Koch brothers who are flooding the political system with their money in order to assure continued dominance of right wing ideologies?

In reply to OneolddudeAug. 1, 2012 at 12:47 p.m.RECOMMENDED32

C'est la blagueNewark

No, because Vidal was right about Buckley.

In reply to IanAug. 1, 2012 at 8:27 a.m.RECOMMENDED32

Maureen MNew YorkNYT Pick

Gore Vidal was a treasure. A neighbor recently left Vidal's memoir "Palimpsest" on the curb in a box of other treasures. It's the cattiest, vainest memoir I've ever had the pleasure of reading and I will treasure it always (regardless of what a NYT reviewer said about it). As mentioned in the obituary, his debates with William Buckley during the explosive 1968 Democratic convention are not to be missed. Thank you, YouTube. How does one judge the 'winner' of such a debate? By the grin on Vidal's face when Buckley explodes after being characterized as a "crypto-Nazi." Vidal was gracious enough to subsequently correct this characterization by saying he meant to say "crypto-fascist" instead. Sublime.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:00 a.m.RECOMMENDED31

RDCNHNYT Pick

I had the the good fortune of being with him at small intimate dinners and in bigger splashy events and in both he made me feel like the "only" person worth talking to once he even saved me from a very painful embarrassing moment (being inappropriately dressed) by calling out my name and silencing the gossips. I owe him big time for that...the last time I saw him he was in pain and cranky and it made me sad but I could still feel the fire in his belly. I am happy we met and I am happier that he is no longer in pain and maybe he is flying through the cosmos with a god at his side, naked!

Aug. 1, 2012 at 11:16 a.m.RECOMMENDED29

Bob BurnsJefferson, Oregon

I seriously doubt Bachmann has the focus to stay with a novel of more than 50 pages.

In reply to Marguerite de ValoisAug. 1, 2012 at 11:14 a.m.RECOMMENDED28

F.X. FeeneySanta Monica, California

"Anyone who thinks my essays are better than my novels hasn't read my novels," he once protested. He was right.

His novels are things of lasting beauty -- icy on the surface and filled with arctic water beneath, yes, much like their maker, but (like the seas under the ice caps) filled with living things. Peter and Caroline Sanford, Myra Breckenridge, Buck Loner -- these characters are as fully brought to life as Julian the Apostate, Aaron Burr and Abraham Lincoln are in his pages.

If all you know are the essays, read the novels. There are forms of cold that burn. His fiction is proof that passion thrives at every temperature

If his editor Epstein still resisted this even after reading the novels in depth, chalk it up to an aesthetic difference -- which is like a religious dispute; there's no answering it in this life.

Anyway: What a century, what an era dies with this man!

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:42 a.m.RECOMMENDED27

mreynaconnecticut

I was a young woman in Panama learning English when I started reading his work. 50 years later I admire him even more. A great loss to this country which is sorely lacking intellectuals and people capable of connecting dots in politics and history.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:29 a.m.RECOMMENDED27

Vaughn A. CarneyStowe, VT

Correction: Gore Vidal, in his famous on-air blow-up with William F. Buckley, called Mr. Buckley a "crypto-Nazi". This was a reference to an incident in Buckley's youthful past, when Buckley and his siblings desecrated an Episcopalian church in Sharon, Connecticut because the rector of that church sold his home on the Sharon village green to a Jewish family in protest of a restrictive covenant prohibiting ownership by Jews.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 11:14 a.m.RECOMMENDED25

ACWNew Jersey

Hitchens, then Vidal, within a year. I don't believe in a god, but if there were one, I'm sure he'd keep one of them at either elbow to entertain Him and keep Him humble. America needs such provocateurs just as Lear needed his Fool.

His best (by my reckoning), were his novel Julian, the rare novel of ancient history that is both plausible and engaging as well as well researched (though it doesn't wear its learning lightly, as its narrators are pedants); and his essays, especially 'The Holy Family' on the Kennedys, one of the first brave efforts to debunk Camelot, published when the 'Martyred St John of Hyannis' myth was still inviolate and inviolable.

And for those of us in the closet, he was an inspiration. Ave atque vale.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 8:59 a.m.RECOMMENDED25

shannonissaquah wa

To write that Wm Buckley called Gore Vidal a queer is to pale a great moment of live TV. It was how he called it that was priceless. For probably the only time in his life he was speechless, Buckley drew back his head, eyes bulging, and sputtered "You, you ...........queer"

Aug. 1, 2012 at 8:28 a.m.RECOMMENDED24

Barbara ScottTaos, NMNYT Pick

I thoroughly enjoyed Mr. Vidal's historical novels.

When "Lincoln" came out in paperback, I read about a fourth of it, then, having found so many errors, returned to the beginning and marked my editorial revisions right on the pages of the book. I sent it to Random House, they forwarded it on to Vidal, and Vidal sent me a (barely decipherable) letter on fine blue stationery from his villa in Italy. It was a lament over the state of publishing in the 20th century. He even took the time to explain some of his literary and stylistic choices (with which, he noted, others had taken issue).

"I sent your comments on to Random House,” he wrote. “Who knows?" I never heard from Random House, but I treasure the blue letter in its hand-addressed envelope.

I would have read "Lincoln" anyway, because it was, to me, a definitive history of that era, and I’ve never forgotten Vidal’s point of view and his compassion toward his characters.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 10:47 a.m.RECOMMENDED23

leonineOhio

Another great truth-teller leaves us. Alexander Cockburn, and now the irreplaceable Gore Vidal; their coruscating commentary will be greatly missed.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:06 a.m.RECOMMENDED22

Robert CoaneOrange County, NY

I would quote Mark Twain: “Go to Heaven for the climate, Hell for the company.”

In reply to IanAug. 1, 2012 at 8:52 a.m.RECOMMENDED22

Thierry CartierIle de la Cite

Vidal was fabulous. He remained a fresh voice much longer than most. His eviseration of Buckley was hilarious. I thought he was a better talker than writer. A unique personality back when people still had personalities.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 11:19 a.m.RECOMMENDED21

DJGDoylestown

Interesting that he thought all humans are inherently bi-sexual. He had the wisdom to see through labels as just meaningless words conjured up by human brains. The mark of a truly intelligent person. I look forward to reading many of his works.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:41 a.m.RECOMMENDED21

TosiaNew York

"Burr" is and has been since I first read it, one of my favorite novels. I bought it for my children and gave it to friends and family because it debunks the mythologizing of our history and our founders like no other work.

With "Burr", Vidal taught me to question the "official" version of history on every level, and he could do this while making me laugh at his wit and delight in his erudition. His American history series should be required reading.

I also recently saw the revival of his "Best Man" on Broadway and was amazed at how completely contemporary the issues were. In some ways, I found it comforting to know from Vidal's work that our country has faced similar problems and had a similar mindset since its inception, so, perhaps, we will survive even this time.

Thank you, Gore Vidal, and go in peace.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:29 a.m.RECOMMENDED21

Mark SiegelAtlanta

I have read and admired Mr. Vidal's works for 40 years. He was in the best sense an old-fashioned writer. By that I mean that his elegant, witty novels play none of the tedious post-modern literary games of too many writers, whose work seems so internally focused. His focus is on character, story, and on creating a believeable fictional world. Among other things, his novels constitute perhaps the best history every written of America. And one more thing: Vidal was refreshingly and wickedly funny, another quality in short supply at the moment.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 11:19 a.m.RECOMMENDED20

Pete KloppenburgToronto

In 2007 I saw him in Toronto, being interviewed on stage by Adam Gopnick. He was hysterically funny, and full of surprises. Gopnick did ask him if he considered himself an novelist first, or an essayist. "Well, it's too late now, I'm a novelist" he responded, drolly.

Gopnick also asked him about the many bon mots ascribed to him on the Internet. He laughed with deprecation, but did name a quote he didn't think he said but thought was so marvelous that he would cheerfully lay claim to: In response to the pro forma invitation to "Have a nice day" from some shop clerk, he was alleged to have responded "I have other plans." This is the story I remember first when I think of Gore Vidal, and I think it captures his mordant wit wonderfully.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 10:46 a.m.RECOMMENDED20

Mark ReneauChattanooga, TN

Gore Vidal lavished the same acidic wit on politicians and governments that Dorothy Parker unleashed on bad plays, books and haughty people. Their voices were much needed, and by the end of their days, mostly ignored. We are lucky that they graced the American stage; there are no replacements waiting in the wings.

Aug. 1, 2012 at 9:06 a.m.RECOMMENDED20

Thomas QuinnFort Bragg, CA

the "crypto Nazi" comment was a quick comeback to Buckley's characterization of the protesters in the streets as such. "If there's any crypto-nazi around here, it's you, Bill"

Aug. 1, 2012 at 12:15 p.m.RECOMMENDED19

ACWNew Jersey

FLAG

Did you just skip the parts of this obit regarding his longrunning relationship with the partner beside whom he will be buried, and his first love to whom he dedicated The City and the Pillar? Not to mention the love letters exchanged between him and Anais Nin, which have been published? Or do you just assume that if you didn't like him, no one could?

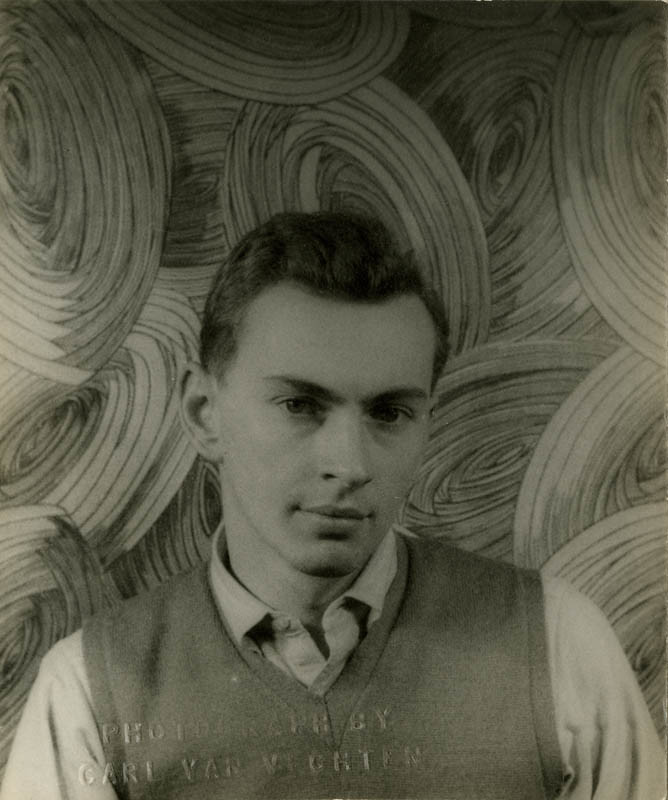

Gore Vidal, a photo by Luis Roiz on Flickr.

Ben-Gore by F.X. Feeney

IN THE “BLACK WINTER” OF DECEMBER, 1953, novelist Gore Vidal checked his bank book and made a life-altering discovery. The novel, while not exactly dead, was killing him financially. “I had been a novelist for a decade,” he would later write. “I had been hailed as the peer of Voltaire, Henry James, Jack London, Ronald Firbank and James T. Farrell. My early, least satisfactory works had been best-sellers. Though not yet 30 years old, I was referred to in the past tense, as one of those novelists of the 1940s from whom so much had been expected.” He was also broke.

This was a bit of long-range fallout from a decision he’d made five years before to publish The City and the Pillar, a ground-breaking novel that provoked shock waves by taking the homosexual relationship of its two central characters in unjudging stride. Vidal’s grandfather, Senator Thomas Gore of Oklahoma, urged him to bury it — he was preparing his grandson for a political career — but young Vidal opted to take the road less traveled and went public with his creation. The book became a bestseller but the furor it touched off was costly. Orville Prescott, critic and editor at The New York Times, told Vidal’s publisher he would never again read, much less review another book by Vidal. Time and Newsweek followed suit. In the years from 1948 to 1953 this amounted to a professional death warrant.

“Driven by necessity,” wrote Vidal, “I took the plunge into television, the very heart of darkness, and to my surprise found that I liked it.” He had a 10-year plan — a straightforward sacrifice of time with the goal of becoming financially independent for life before sitting down to his next novel. In 1954 alone, he was credited with 20 TV plays. (“And that’s not counting the 20 I wrote that year under other names,” he told a 1994 audience at the Museum of Television & Radio.) For his first TV play, Dark Possession, he was paid $750 — and this in a period when taxes took a bite of 90 percent.

He was in no mood to quarrel over figures; TV had become such a phenomenon that there were other, weirder rewards. “It was a miraculous time for the writer. A play would be done live for as many as 20 million, 40 million people — you’d be walking down the street the next day and overhear people at the corner, discussing your play. One knew what it was like to live in Athens in the time of Pericles.” (Unfolding this analogy 40 years later, Vidal stopped himself to chuckle; “Imagine me, erring on the side of optimism.”) This bright epoch came to an end several seasons later with the rise of quiz shows, “which were cheaper to produce — but for a time television was a writer’s medium. We created it.”

¤

Hollywood became a logical destination. Vidal accepted a contract at MGM and in quick succession wrote two scripts for producer Sam Zimbalist, The Catered Affair and I Accuse, as well as one for British mogul Michael Balcon,The Scapegoat. He participated in the writing of Ben-Hur. Meanwhile, Visit to a Small Planet, which began life as a TV play, became a Broadway hit — “a successful play will earn its author a million or more dollars,” he observed in a 1976 essay about Tennessee Williams — and so his 10-year plan had by 1959 come to an early fruition.

He cleverly expanded a Williams play, Suddenly Last Summer (1959), subtly harmonizing with and preserving the playwright’s voice yet providing a stronger external structure, and magnifying the original like a rose in a ball of crystal. He wrote still another Broadway hit, The Best Man, a political shadow-play devised in part to help John F. Kennedy. “I thought it would be fun to do a play in which the sexually promiscuous man is politically the noblest man in the United States, whereas the All-American boy with the perfect marriage is a would-be Hitler.” (JFK suggested a line that went straight into the play: “When you want to slip the knife to a politician, tell him: ‘You always know where to reach me.’”) After a try at running for Congress himself, Vidal returned to the novel, and when Julian was published in 1964, none other than Orville Prescott was there to greet it, coming out of retirement to end the Times boycott.

Vidal didn’t care. Free to fail if need be, free to pursue whatever topics he pleased at his own pace, he created the body of work for which he is best known and will be remembered. His historical novels, especially Burr andLincoln, have widely influenced how Americans view their own history. (The notion of Lincoln as a willful, steely genius — as opposed to the folksy demigod of Carl Sandburg — has gained enormous currency in the last three decades, and this is Vidal’s doing.) His “hyper-novels,” particularlyMyra Breckinridge and Myron, infuse contemporary American life with an edge of dreamy, downright pagan farce. His essays are a body of work unto themselves — a lucid, often hilarious exploration of our political and cultural life. In the piece recalling his career as a dramatist, Vidal declares: “The novel is the more private and (to me) the more satisfying art. A novel is all one’s own, a world fashioned by a single intelligence, its reality in no way dependent on the collective excellence of others.”

And yet clearly Vidal benefited as a novelist from his time spent writing scripts. There is an almost violent difference in scale and power between the novels that preceded his career as a dramatist and those which come after. Conversations, exposition, all become sharper in Julian, and beyond; individual episodes become more concentrated. Despite the upholstered luxuries of their prose, a dramatist is quietly at work in the basements ofMyra, Burr, and Lincoln, making sure things upstairs heat and cool on schedule. Size — the most obvious difference in Vidal books Before and After — is likewise no accident; the narrative energy delivering one’s attention across these Michener-like spans derives from a ruthless sense of necessity that operates in even the tiniest of scenes.

¤

“I am not a naturalist playwright. In fact, I am not a playwright at all, though I seem to be turning into one,” he explained in 1966. “Primarily I am a prose writer with axes to grind, and the theatre is a good place to do the grinding in. I prefer comedy to ‘serious’ drama because I believe one can get the ax sharper on the comedic stone. […] When the mask is Comedy, the face beneath can be that of […] a hanging judge and the audience will not be alarmed; they will laugh and in the laughing listen, sometimes to good effect.”

Writing for the stage and screen continued to attract him, as a healthy diversion between books. For the quarter century that followed Julian he wrote a dozen film and TV scripts, some negligible: Is Paris Burning (1967);The Last of the Mobile Hotshots (1969). The former was a favor he did for producer Ray Stark, rewriting an earlier pass by Francis Coppola. The latter was a steamy gothic comedy spun from a Tennessee Williams one-act, The Seven Descents of Myrtle, for director Sidney Lumet. A “mistake,” was Vidal’s cheerful verdict years later, “as I was in demand after Suddenly Last Summer to adapt practically anything that Tennessee wrote.”

Most of Vidal’s dramatic work involves adaptation. His early teleplays include two highly effective distillations of William Faulkner (Smoke; Barn-Burning) as well as Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, which he renders in six or seven scenes. Part of this preference was practical: “I dislike writing treatments,” he explained, “those pidgin-English outlines which are expected to record in detail the events of an unwritten play… Easier, I should think, to divine the nature of an unborn child.” What’s more – because sponsors and their advertising teams seemed compelled to interfere with original work – it was easier to accept an assignment on a story that was already approved. Yet he was enthused about adaptation for more energetic reasons.

“How is a novelist born?” he once asked, recollecting his boyhood: “Whenever I read something I liked, I had a tendency to start writing my own novel in competition.” Discussing Romulus, a 1966 Broadway production he adapted from a German original by Friederich Duerenmatt, he added: “In our ‘serious’ theater it is thought parasitic for a writer to adapt the work of another writer for the stage… Yet the Greeks, Romans and Elizabethans were primarily adapters. Shakespeare was the greatest adapter of them all… [He] used anything that came to hand; if anyone had a plot he fancied or a character he wanted to explore, he took it.”

The excitement of taking a ready-made story surely activates Vidal’s imagination the way writing about historical figures ignites his best novels.Dress Gray (1986), a movie for television based on the best-selling novel by Lucian Truscott IV, centers on a sexually tinged murder between cadets at West Point. This was right up Vidal’s alley on several grounds. He was born at the Point, where his father was an instructor; the frank treatment of homoeroticism in macho military disguise allowed him to amplify what he’d trail-blazed in The City and the Pillar, in more receptive times. The script had first been drafted in the late 1970s, originally for a theatrical release: I’d run across a copy then and was struck by the punchy brevity of the stage directions, very much in Vidal’s voice, which memorably specified a close shot of two cadets squaring off in profile nose-to-nose in attitudes which expressed both their war with each other and their attraction.

The Palermo Connection (1989) directed by Francesco Rosi is a cleanly delineated if too slowly paced drama of an idealistic American politician, cornered by the mob while on vacation in Sicily with his wife. The poet Tonino Guerra – who also wrote scripts for Antonioni, Fellini, Tarkovsky and Angelopoulos – made an earlier pass, based on the novel by Edmonde Charles-Roux. Vidal then rewrote it into American vernacular and the film’s dialogue is particularly sharp with his political savvy.

Perhaps we should define what we mean by “politics” here. Given that he’s been a loyal scourge of U.S. war policy from Vietnam through Iraq, not to mention the self-hypnoses of our mass-media and the countless disastrous choices of most of our Presidents, we might easily expect Vidal to thunder sermons in his imaginative work. He resists this. As a dramatist his politics are neither right nor left wing but instead center on movements and tradeoffs of power between matched adversaries at intimate range. These conflicts are so concentrated in turn that we are invited to think, and in thinking contemplate, a skeleton of moral sense beneath – one that richly suggests alignments and treacheries within society as a whole.

¤

His characters are acerbic. Even his crudest, least articulate protagonists such as Billy the Kid express a forceful skepticism that energizes their actions as they attract both loyalists and killers. One woman asks Billy, after he’s killed so many men that his doom is inevitable: “Do you feel you been bad?”

“I don’t think about it.”

She persists. “It’s not right to kill.”

“It’s right to live,” he replies, “and I wouldn’t be living if some other people hadn’t died along the way.”

The Death of Billy the Kid (1955) was Vidal’s personal favorite of his many early teleplays. It was also the most severely criticized, for reasons he found wrong-headed. Some complained that the title gave away the ending. Others decried it for presenting us with a cold-blooded protagonist without explaining him psychologically. “I was aiming, no doubt inaccurately, at tragedy and I wanted a massive effect, a passionless inevitability which I believe, all things considered, the play’s production achieved.” The life of William Bonney and his fatal squaring off with his former friend Pat Garrett originally interested Vidal as the theme for a novel. “I knew exactly what I wanted to do with the legend, but Billy himself proved a considerable problem: How to show him? What, after all, could one say about a cold-blooded little killer who, in the words of a noted psychiatrist, was ‘an adenoidal moron?’ I could not in all honesty make him an introspective human being aware of the startling design he was creating … Billy was precocious, as the nation was, ruthless, as the nation was and still can be. Despite the cruelty of his ways there was something in him which struck fire in the imagination of others and those who knew him realized early in his progress that he was not ordinary, that he was meaningful in a way few men are; that the meaning was essentially dreadful was a problem only to the reflective man. His appeal was to those deeper emotions which he evoked by the mere fact of existing.”

Vidal managed to convey this mystery in ten or eleven highly effective scenes – 47 minutes of screen-time with the balance of the hour going to commercials – and he had the benefit of a lead performance by Paul Newman, who as he saw it “managed with discretion and power to interpret a nearly impossible role: he had to be, simultaneously, both wicked mortal and potential godling.”

A lifelong friendship with Newman was one result. Another, less satisfactory, was the film directed by Arthur Penn called The Left Handed Gun (1958), also starring Newman, whose screenplay by Leslie Stevens used – at most – two or three lines of Vidal’s play, and reinterpreted Billy as a Troubled Youth in the James Dean mold, petting his stomach as he tilts back against the nearest wall, squinting at an unseen heaven and mumbling to himself about Havin’ Feelin’s – or Not Havin’ ‘Em. … Imagine an aw-shucks Hamlet without words, and a six-gun to do his thinking.

Vidal was appalled (“Arthur Penn is an Iago in permanent pursuit of an Othello,” he laughed, decades later) but at the time coldly put this behind him, as he would two years later when the film version of Visit to a Small Planet (1960) torched the nuances of his play to become a vehicle for Jerry Lewis. At the very least these wasteful adaptations provided the paydays with which Vidal could complete his planned-for treasury.

The Best Man (1964) nearly met the same downfall. Originally Frank Capra was set to direct, and he proposed new scenes filled with his own brand of sentiment and emotion. He wanted the Presidential candidate played by Henry Fonda to dress up like Abraham Lincoln as he addressed the delegates on the floor in an opening scene. Fortunately, Fonda agreed that this would be a disastrous choice, giving Vidal the clout to show Capra the door and replace him with Franklin Schaffner, who had directed his debutDark Possession in 1954.

As a result The Best Man is Vidal’s most original film, the one fully expressive of his dramatic sense and world-view. Its closest rival is Billy the Kid (1989), Vidal’s final screenplay, which lifts the curse of The Left Handed Gun and, almost as a valedictory, brings to life his original ambitions for the story. (Unfortunately the passage of thirty years means it must compete amid a whole playground of other Billys – especially Rudy Wurlitzer’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, directed by Sam Peckinpah.) Thus The Best Manremains most purely a creature of Vidal’s imagination and expertise.

“I don’t mind your headline-grabbing and crying ‘Wolf’ all the time,” the outgoing President tells a fear-mongering super-patriot played by Cliff Robertson: “It’s par for the course trying to fool the people but it’s downright dangerous when you start fooling yourself.” Later, when the conscientious front-runner played by Fonda agonizes over whether he should use an item with which he could destroy Robertson – solid proof that this holier-than-thou macho had a homosexual affair in the army — the President scorches such reluctance: “Power is not a toy we give to good children; it is a weapon, and the strong man takes it and he uses it.” That line is a direct quote from Vidal’s late grandfather Senator T.P. Gore. It is this lived-in quality to his insights that keeps his politics from being preachy.

The film’s performances, rhythm and black & white cinematography all were superbly directed, but when the picture opened at the Cannes Film Festival Vidal discovered to his lasting irritation that the posters for Le Bon Homme lining the Croisette made no mention of his own contribution but instead proclaimed “Un film de Franklin Schaffner.”

This led to a particularly nasty trip through the looking glass a decade later, when (following the example of Fellini 8 ½, Fellini Satyricon and Fellini Roma) he wrote an original epic which he christened Gore Vidal’s Caligula(1979). Ironclad contracts guaranteed this, but the subsequent ordeal ended with Vidal suing to remove his name altogether. “I should have directed it myself,” he later lamented. Malcolm McDowell, Peter O’Toole, John Geilgud and Helen Mirren no doubt share his pain. They were seduced by his screenplay, only to find themselves in bed, so to speak, with Italian director Tinto Brass (“Tinto Zinc,” O’Toole called him) and Penthousepublisher Bob Guccione. The result is an incandescent mess — a hardcore porno with great dialogue. Geilgud’s parting speech to O’Toole, as he bleeds into his bath and makes a Houdini-like escape from these proceedings, has the sharp music of what-might-have-been: “I’ve lived too long, Tiberius, and I hate my life ... For a man to choose the hour of his own death is the closest he will ever come to tricking fate.”

¤

In his 1976 essay: Who Makes the Movies? Vidal asserted that, “For all practical purposes, the screenwriter continues to be the primary creator of talking film.” Apart from such exceptions as Hitchcock, Welles and Bergman, a typical film director is at worst a brother in law and at best a technician, a “hustler-plagiarist who has for twenty years dominated and exploited and (occasionally) enhanced an art form still in search of its true authors.”

This essay kicked up an entertaining controversy about the making of Ben-Hur. In addition to showing off one writer’s mind in clever action it repays close study as an example of how we might track any individual’s contribution to the “authorship” of a given film, even in the context of the Hollywood assembly line.

Vidal flew to Rome with producer Sam Zimbalist and director William Wyler in the spring of 1958. His assignment was to develop a psychological motivation for the quarrel that erupts between two former friends, Massala and Ben-Hur — a feud that must fuel a whole four-hour epic, “until” as Vidal describes it, “Jesus Christ suddenly and pointlessly drifts onto the scene, automatically untying some of the cruder knots in the plot.” Wyler and he “agreed that a single political quarrel would not turn into a lifelong vendetta,” so Vidal proposed something primal: “As boys they were lovers. Now Messala wants to continue the affair. Ben-Hur rejects him. Messala is furious. Chagrin d’amour, the classic motivation for murder.”

This being the 1950s, the story being an adjunct to the Bible, and the star being Charlton Heston, Wyler understandably balked, but Vidal reassured him: “We won’t really do it. We’ll just suggest it. I’ll write the scenes so that they will make sense to those who are tuned in. Those who aren’t will still feel that Messala’s rage is somehow emotionally logical.” Wyler, his back to the wall with an otherwise unworkable script, agreed to the scheme, but issued a now legendary warning: “Don’t ever tell Chuck what it’s all about, or he’ll fall apart.”

Heston, waking up at the butt-end of this punchline decades after the fact, understandably — if grimly — disputed this yarn for the rest of his life, carrying his campaign from the pages of Time magazine to the midnight airwaves courtesy of Bill Maher. “What are we to make of Gore Vidal?” he asked, in a letter circulated to a number of Op-Ed pages. “He’s determined to pass himself off as a screenwriter, particularly of Ben-Hur... He was in fact imported for a trial run on a script that needed work. Over three days (recorded in my work journal), he produced a scene of several pages which Wyler rejected after a read-through with Steve Boyd [the actor playing Messala] and me. Vidal left the next day.” In cold fact, Heston’s “work journal” — published as The Actor’s Life in 1978 — shows Vidal was on theBen-Hur set not just for three days, but well over a month.

But to harp on this tussle misses the key point of Vidal’s essay, which was “to show the near-impossibility of determining how a movie is actually created.” Memories are fickle; only producer Sam Zimbalist (who preceded Wyler onto the project and brought Vidal aboard) knew which of the five writers involved was responsible for which contribution, and he died of a heart attack before credit could be arbitrated. Karl Tunberg (an MGM contract writer involved years before, as well as a former President of the Writer’s Guild) received the sole screenplay credit; in treating the episode, Vidal’s purpose was not to torment Heston but to belatedly establish himself and playwright Christopher Fry as the actual authors of the Ben-Hurscript. He was also aiming a heat-seeking missile at the heart of the auteurtheory.

¤

To test its accuracy I spent the better part of a month studying as many Vidal teleplays and movies as I could lay my hands on — twelve, in all — as well as both texts of Visit to a Small Planet (stage and teleplay; the kinescope has been lost, alas); Heston’s journals; the Christopher Fry screenplay forThe Bible; and – most tellingly – the multicolored shooting script for Ben Hur archived at the Academy library, in which each page is dated. What emerges fast – especially watching the films and kinescopes chronologically – is that Vidal’s verbal signature is not just identifiable, but his screen work vivid and continuous from film to film. One could well imagine Turner Classics bringing out a boxed set, “The Films of Gore Vidal.”

An unbroken line of development comes right at the beginning, when he was at MGM working with Zimbalist. Richard Brooks may have directedThe Catered Affair, but the film bears no visible relation to The Professionalsor Bite the Bullet, films Brooks later wrote himself and which very much bear his stamp. What The Catered Affair most resembles is the film Vidal wrote directly after — again for Zimbalist, directed by its star, Jose Ferrer: I Accuse. The complexities of the Dreyfuss case, which rocked the French government to its roots in the 1890s, are laid out in thirty leanly crafted, straightforward scenes. The abundance of treachery and corruption give Vidal’s best wits and insights room to joust and maneuver.

“All our men dislike change on principle,” a kindly officer warns our hero in an early scene, “but it is something of an innovation — having a Jewish officer.”

Dreyfuss, who will nearly be crushed by such institutional Anti Semitism, is someone we need get to know and love in the space of a very few scenes. The traps the fates are laying for him are so intricate they will require the greater part of our attention. Thus, early on, Captain Dreyfuss finds his young son kneeling at play before a little army of toy soldiers.

— How is General Dreyfuss tonight?— I stopped Kaiser.— Did, eh? Supply lines intact?— Yes, captain.— Communications established?— Yes, captain.— Reserves in readiness?— Yes, captain.— Good. Carry on, General.

A man’s tenderness toward his boy and his devotion to professional duty, simultaneously established in one compact encounter.

After drafting Ben-Hur, Vidal was invited to England by Michael Balcon to do The Scapegoat (1959) based on a Daphne du Maurier story. Director Robert Hamer is credited with “screenplay,” Vidal with “adaptation,” but the tensile strength of the story’s arc and the sharp, incantatory metrics in the dialogue put it on the same shelf as The Catered Affair and I Accuse.

In The Scapegoat, Alec Guinness plays a quiet, unaccomplished Englishman on holiday in France. He and a local nobleman chance across one another in a pub and discover they are physically identical – virtual twins. This is amusing to the traveler, but to the aristocrat (facing deadly financial pressures) it inspires, in the manner of Strangers on a Train, a murder scheme. The innocent Englishman wakes up with a hangover and discovers he’s been forced to take over his seedy lookalike’s whole complicated identity, complete with a nagging wife, a racy Italian mistress, a French chateau and a half-blind grand Duchess for a mother, played wonderfully by Bette Davis.

Nobody seems to catch on to the imposture. The resemblance is that total. If anything, the dowager is merely irritated at the uncharacteristic generosity her “son” is suddenly showing to the local poor. She demands to know:

— What’s happened to you while you were away? It’s almost as if you were a different person.— I am, as I’ve been trying very hard to explain.— You can’t go and get mixed up in politics.— You can’t go and let people starve.

For all that he’s been cornered into a game that may kill him, this stranger finds he likes wielding power and quickly cultivates the wit to defend it.

Because Vidal entered the field as an established novelist, he had a practiced grasp of narrative. He also had humility about the requirements of writing for actors, and took to heart a piece of advice from Henry James: “Theater is not an art but a secret.” His people don’t speak prose; they address each other straightforwardly, without embellishment. However sharp the rejoinders, we never “hear the dialogue;” we hear the characters.“People do not listen to words,” he discovered when writing for television. “This is due perhaps to habits acquired in everyday life, where conversations are dependent not so much upon the use and arrangement of words and ideas as on certain familiar tones of voice, gestures, hesitations.”

Finding the right structure became key: not in any formulaic, storytelling-by-the-numbers sense, but of finding the right fulcrum – for example, slowing down the story of Billy the Kid, concentrating on key moments in contrast to the severely limited running time of the piece, or in The Best Man of moving back and forth from one rival camp to another with a soon-to-be-former President acting as a humble foil-figure and go-between. Brought aboard to script The Sicilian (1987), Vidal told director Michael Cimino, “I don’t ‘see’ anything, so don’t bother me with action. I’ll do the characters and introduce the themes.”

¤

In Dark Possession, the handsome young Doctor played by Leslie Nielsen stamps his feet as he comes into the foyer and greets his fiancee.

— They’re outside! The new horses.— They must be freezing! They’re not used to our winters.— Oh! They’re all right.

A completely innocuous exchange (one Vidal later deleted from the published text), but that by its rhythmic brevity catches the frosty breath and nervous mood of a snowy day, vital to moving forward a house-bound who-done-it. Notice, also, the light-footed way the words “they’re” and “they”repeat from speaker to speaker. Repetition is a trait one can mark in any number of excellent playwrights, but how words repeat and why bears the imprint of an individual mind and ear. David Mamet’s people repeat forcefully, like boxers, proving points with verbal punches. In the work of Christopher Fry, repetition hits the lyric organ-note of a responsorial psalm.

In Vidal’s case, repeat-words are a subtle, organic constant, and advance his notion (a key theme in all his work) that even the most casual conversation is a form of duel. “This can’t be happening to me,” says the domineering mother in Summer Pavilion. Her daughter shoots back: “This isn’t happening to you, Mother. It’s happening to me!”

Wit fights fire with fire; the snap of provocation and response that are Vidal’s trademarks give even routine bits of exposition a clever intensity. Notice the melodic repetitions in The Catered Affair, in which a New Jersey mother played by Bette Davis has this exchange with her son:

— Eddie, your sister’s marrying Ralph.— That’s good [he grunts].— That all you got to say?— Congratulations.— Eddie, your sister’s marrying Ralph.— I heard you, that’s what you said, she’s got him, so good.— I never seen less family spirit.— Who’s got spirit? I got nothin.’ Next month in Fort Dix, the army’s got nothin.’

Blue collar reality isn’t exactly Vidal’s native beat — he was radically adapting The Big Deal, a teleplay by Paddy Chayevsky — but the above conversation, the very existence of Eddie (new to the script), indeed all ofThe Catered Affair as it now stands, is original Vidal dialogue. To make a seamless film-script out of this chamber drama required throwing everything away but the original intention. Theme, anguish, basic premise — these are Chayevsky’s, and Vidal honors them with bold improvisation. Ironically, in 2007, when Harvey Fierstein and John Bucchino commemorated their love for this movie by turning it into a Broadway musical, it wasn’t until last minute that somebody actually compared scripts and realized they were adapting Vidal while tickets were being sold on the Chayevsky name. Vidal took the apologetic phone call that followed in stride: “I did not wish them ill and made no fuss.”

¤

The narrative voice of his novels is a droll, mischievous, Orson Wellesian presence — but Vidal escapes this entirely when writing dialogue for actors. He can mimic old men, peasants, Southern belles, visitors from outer space with equal freedom and absence of strain. His excitement is contagious in the early scripts. Certain familiar obsessions crop up. Historical references abound — in Dark Possession, the elderly father recalls that he heard Lincoln at Gettysburg, “but preferred the speech made by the other fellow.” Aphorisms about power crop up everywhere — the Vidal songbook in this line is The Best Man, with its hit singles, “Power is not a toy we give to good children,” “The self-made man often makes himself out of pieces of his victims,” and “That man has all the qualities of a dog, except loyalty.”

A defining Vidalian trait might be termed the “silent turnabout.” In I Accuse,when her husband has been arrested for treason and the whole world is against her, Mrs. Dreyfuss notices with dread that the lawyer she engaged has gone ominously grave. “When you came to me,” he tells her, “I said I would defend your husband if I believed him innocent...” (She turns to face him, and we brace ourselves, but are surprised:) “Well — I do. …I’m more than ever convinced.”

Such peripeteia form the basic grammar of a dramatist. Vidal is especially adroit at planting such skipped heartbeats, though — time and again, characters catch one another off guard. Even in friendship, the winning duelist keeps his listener guessing.

The dialogue in The Sicilian has all his earmarks:

— Your son is a scholar, Don Masino...— My son does not exist.

This much-maligned movie deserves a look, if you’ve never seen it – indeed, it deserves a second or third look if you haven’t seen it in a while. (The director’s cut is available on DVD.) What matters in this context is that, once again, Vidal was denied his due acknowledgment. The screenplay is credited to Steve Shagan, who adapted Mario Puzo’s novel before Cimino signed on and brought Vidal aboard – but when I interviewed him in depth on this topic for LA Weekly, Vidal was emphatic that he alone wrote what got filmed.

“I have a simple question I’d like to submit to every member of the Writer’s Guild,” he smiled: “True or False: Would Gore Vidal ever want credit for anything written by Steve Shagan?” More seriously he sued the guild, as much in repayment for Ben Hur as for the Sicilian matter. “They have institutionalized plagiarism, and I don’t like that.” He and the WGA fought all the way to the Supreme Court of California, “which found in my favor,” he writes, in Snapshots in History’s Glare. “This lawsuit was my quarter-of-a-million-dollar gift to the membership of the Guild. No longer need they accept as ‘final’ the judgments of three anonymous hacks [assigned to arbitrate screen-credits].”

He had originally embraced the assignment of The Sicilian as a chance to freshly address the tragic theme of The Death of Billy the Kid, particularly the reluctance of the lawman Pat Garrett, whom he once described as “driven by pride to measure himself against a hero, to become the hero by destroying him.” In The Sicilian the same outline applies. Don Masino’s courtship of a substitute son in the renegade outlaw, Salvatore Giuiliano, is the emotional mainspring that drives the film. We know from the beginning that the tale will, somehow, some way, end at Giuliano’s grave. When it does Don Masino, who had him killed, stands with his confidante Professor Adonis and sheds tears like a bereft father. Their conversation, which powerfully concludes this film, is pure Vidal:

DON MASINO

(weeping)

Why couldn’t he — why wouldn’t he — come to me?

ADONIS

Why should he? He was his own father. He invented himself, and we killed him ... You and I ... Now he’s gone.