Marking Infinity presents the work of artist-philosopher Lee Ufan, charting his creation of a visual, conceptual, and theoretical terrain that has radically expanded the possibilities for painting and sculpture since the 1960s. Lee is acclaimed for an innovative body of work that revolves around the notion of encounter—seeing the bare existence of what is actually before us and focusing on "the world as it is."

Lee was born in southern Korea in 1936 and witnessed the political convulsions that beset the Korean peninsula from the Japanese occupation to the Korean War, which left the country divided in 1953. He studied painting at the College of Fine Arts at Seoul National University and soon moved to Japan, where he earned a degree in philosophy. Over the last 40 years, he has lived and worked in Korea, Japan, and France, becoming a transnational artist in a postmodern world before those terms were current. "The dynamics of distance have made me what I am," he remarks.

In the late 1960s, in an artistic environment emphasizing ideas of system, structure, and process, Lee emerged as the theoretical leader of Mono-ha (literally, "School of Things"), a Japanese movement that arose amid the collapse of colonial world orders, antiauthoritarian protests, and the rise of critiques of modernity. Lee’s sculptures, presenting dispersed arrangements of stones together with industrial materials like steel plates, rubber sheets, and glass panes, recast the object as a network of relations based on parity among the viewer, materials, and site. Lee was a pivotal figure in the Korean tansaekhwa (monochrome painting) school, which offered a fresh approach to minimalist abstraction by presenting repetitive gestural marks as bodily records of time’s perpetual passage. Deeply versed in modern philosophy and Asian metaphysics, Lee has coupled his artistic practice with a prodigious body of critical and philosophical writings, which provide the quotations that appear throughout this exhibition.

Marking Infinity is organized to reflect Lee’s method of working in iterative series and spans the 1960s to the present. Whether brush marks on canvas or stones placed just so on the ground, his markings in space elicit momentary, open-ended situations that engage the viewer viscerally. His distilled gestures, manifesting an extraordinary ethics of restraint, create an emptiness that is paradoxically generative and vivid. Relatum (formerly Phenomena and Perception A, 1969) presents three rocks laid on a latex band marked as a measuring tape. The weight of the rocks causes the band to stretch and buckle, disrupting the system of measurement it codes and reminding us of the capriciousness of rational truth: what you see is a result of where you stand.

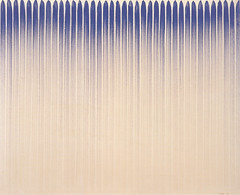

Lee’s early painting series, From Point and From Line (1972–84) present a minimal, gestural act that induces in the viewer a lived experience of passing time and physical (rather than depicted) space. In these works, Lee combines ground mineral pigment with animal-skin glue, traditional to East Asian painting on silk. Restricting his palette to a single color on a white ground—colbalt blue or burnt orange, evoking sky or earth, respectively—Lee loads his brush with this powdery, crystalline emulsion and, in From Point, marks the canvas with regular dabs from left to right until there is no more color left. He then repeats this act until rows of gradually fading marks fill the entire canvas. The From Line series pursues a similar systematic approach, moving vertically with single gestural strokes. Lee uses the means of abstract minimalism—seriality, the grid, and monochrome—to alternative ends, emphasizing the gestural mark, the edge, and surface as physical affirmations of existence.

Since his early Mono-ha period, Lee has restricted his choice of sculptural materials to steel plates and stones, focusing on their precise conceptual and spatial juxtaposition. The steel plate—hard, heavy, solid—is made to build things in the modern world; the stone, in its natural as-is state, “belongs to an unknown world” beyond the self and outside modernity, evoking "the other" or "externality."

Arranging the plates in precise relationships to the stones, Lee’s Relatum series (1968– ) presents a durational form of coexistence between the made and the not made, the material and the immaterial elements of our surroundings. The series title is a philosophical term denoting terms, objects, or events between which a relation exists. In Lee’s mind, the occasion of the site-specific work and the network of dynamics it triggers is more important than the object per se, and we the viewer enter the scene as an equal part of the whole.

The show concludes on Annex Level 7 with an installation of Lee’s Dialogue painting series (2006– ). Lee has created a site-specific installation placing a single, broad, viscous stroke of paint on each of three adjacent walls of the empty room. Dialogue–space (2011) sets up a rhythm that exposes and enlivens the emptiness of the space, creating what Lee calls "an open site of power in which things and space interact vividly."

—Alexandra Munroe, Samsung Senior Curator, Asian Art

Lee switches on some music in the studio. He likes Mozart, Bach, and Debussy. Contemporary music, he says, disturbs his concentration. On one wall are rows of philosophy books; on another, paintings on racks. Rooms to the left and right are used for storage and displaying paintings for visitors. Although small, the space is luxurious by Japanese standards. It is also extremely peaceful, with a direct view of the bamboo grove through two large glass doors.

Lee works quickly and quietly, laying a prepared canvas on the floor, then getting brushes, powdered pigment, and bottles of oil-based binder from shelves below the bookcases. Twenty minutes pass as he mixes the paint, blending white and black to get the grainy blue gray that is his hallmark hue. He selects a brush from a hanging rack and begins to load it with paint.

He makes a single, slow, deliberate downward stroke on the canvas and goes over it again and again until all the paint is transferred from the brush. He refills it and begins the process again, this time pushing down heavily at the beginning of the stroke to create a lip or ledge of excess paint, some of which he gradually smooths out.

On average it takes Lee about a month to finish a painting, on canvases that typically measure about 60 by 90 inches, although they can vary in size from a few inches to 10 feet per side. He works on a canvas for a couple of hours, then leaves it to dry for a week, doing this three or four times until he has built up a thick layer of paint. He tells me he does not know how many layers it takes to complete a pattern, each of which is slightly different. Although the strokes resemble one another, the execution varies depending on the humidity and temperature and the composition of the pigments in the final application. Lee completes no more than 25 works a year.

His goal is simple: to create powerful graphic images that arouse or evoke instant feelings of serenity. Indeed, his repetitive pictures are surprisingly engaging, even mesmerizing. The attraction lies partly in the vibration of the patterns — which are dense, gritty, and almost sculptural — and partly in the ambiguous relationship between inside and outside, figure and ground. Because his paintings operate as much on a visual level as on one of ideas, Lee is not strictly a Conceptual artist.

Lee has been painting the same thing — brushstrokes — since the 1960s, when his compositions consisted of repetitive arrangements of smaller multiple swipes. About 15 years ago, these were pared down to one, two, or three larger marks, to create a more concentrated and formal impression and also to deemphasize repetition while stressing the relationship between the painted and unpainted parts of the canvas. Extra-wide custom-made brushes enable him to produce the specific breadth he wants. "Color is not so important here," he tells me, putting down the first stroke. "The most important things are placement and texture."

Lee paints for about two hours a day, then breaks for lunch. During the afternoon he reads, makes telephone calls, or, a few times a week, goes to Tokyo to view art shows. "I don’t do so much writing anymore," he says. "I have many ideas. I just don’t find the time." Over the years he has authored 17 books of poetry, art history, and criticism on topics as diverse as Conceptual art, sculpture, and German philosophy.

In a way it was philosophy that brought Lee to Kamakura more than 50 years ago, in 1959. That summer one of his philosophy professors, Yoshio Sezai, invited the artist to mind his house in the city, at the time a haven for Japanese artists, writers, and thinkers. The authors Kitaro Nishida and Yasunari Kawabata lived there, and Lee met and conversed with them. He fell in love with the place and later, when he landed a job as a professor of art at Tama Art University, in Tokyo, decided to return there to live.

Lee began to study painting at Seoul National University’s College of Fine Arts. At 20 he moved to Tokyo and enrolled in the philosophy and art departments at Nihon University. He spent his early working years juggling careers as an art critic, philosopher, and artist. He came to prominence in the last role in the 1960s, as the leader of the Mono-ha earth-art movement. Mono-ha artists, like their peers in the U.S. and Europe, were interested in blending nature with art and vice versa.

His sculptures from this period are composed of steel plates, glass stones, lightbulbs, rubber, cotton, paper, and wood and tend formally to resemble Arte Povera or post-Minimalist works. His intention, Lee says, was not to dominate or reshape his materials, as other, more traditional sculptors do, but to reveal their intrinsic qualities through juxtapositions or what he calls "re-presentations." Rarely exhibited examples of these pieces will be in the Guggenheim retrospective, which will comprise 90 works from the 1960s to the present, installed throughout the building. "Lee’s sculptures are part of the radical disappearance of the art object in the late ’60s and ’70s, when art shifted from being an entity unto itself to becoming a fluid and dynamic event occurring in real time and space," says Alexandra Munroe, Samsung senior curator of Asian art at the Guggenheim. "Lee took himself out of the equation of the creative act, allowing the relationships among viewer, materials, and site to stand in for the experience of art."

Lee continued to paint throughout the 1960s and ’70s, making monochromatic formalist paintings out of repetitive arrangements of multiple brushstrokes. These works are intimately connected to his sculptures, emphasizing process and materials and the overall experience of art emerging from a set of relations in a given environment. Here too the artist does not try to dominate or cover over all the canvas but rather creates conversations among figure, ground, and wall. "Canvases are industrially produced, a neutral field of expression linked to the walls and surrounding environment," Lee explains. "In other words, they stand in the intermediary position between the interior and the exterior, and the simplest touches on the canvas radiate. Therefore, it is not only the simple touches on the canvas but also the resonant vibration that is emitted from the canvas onto the wall and into the environment that make it a painting."

More prosaically, Lee has described his work as "the art of encounter," a phrase he also used as the title of his 2004 anthology of English-language essays. To me this seems a more direct description and an entirely accurate one, for although his artworks have little immediate content, they are not devoid of subject matter. Relations of time and space — these are the real themes explored in the artist’s large and inventive body of work, even if they are sometimes hard to see. (Benjamin Genocchio @ http://www.artinfo.com)

A Fine Line: Style or Philosophy?

By KEN JOHNSON

For the hot, tired and frazzled masses, the Guggenheim Museum offers an oasis of cool serenity this summer. “Marking Infinity,” a five-decade retrospective of the art of Lee Ufan, fills the museum rotunda and two side galleries with about 90 works in a Zen-Minimalist, be-here-now vein.

Mr. Lee, 75, is an aesthetic distiller. He boils two- and three-dimensional art down to formal and conceptual essences. Sculptures consist of ordinary, pumpkin-size boulders juxtaposed with sheets and slabs of dark, glossy steel. Paintings made of wide brush strokes executed in gridded order on raw canvas exemplify tension between action and restraint.

A much published philosopher as well as an artist who divides his time between Japan and Paris, Mr. Lee has enjoyed considerable recognition in Europe and in the Far East. Last year the Lee Ufan Museum, a building designed by Tadao Ando, opened on the island of Naoshima, Japan.

But Mr. Lee’s reputation has not extended to the United States. This exhibition, his first in a North American museum, gives a sense of why. His art is impeccably elegant, but in its always near-perfect composure, it teeters between art and décor.

His sculptures call to mind those of Richard Serra, but shy away from the brute physicality of Mr. Serra’s works; his paintings invite comparison to those of Robert Ryman, but are less pragmatically inventive. In its modernization of classical Asian gestures, his work is more suavely stylish than philosophically or spiritually illuminating.

It is interesting to learn, then, from the well-written catalog essay by Alexandra Munroe, who organized the show and is the Guggenheim’s curator of Asian art, what a turbulent environment of art and politics Mr. Lee came out of. He was born in Japanese-occupied Korea in 1936. He studied painting in Seoul and philosophy in Japan, where he moved in 1956.

Steeped in the phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger and in Marxist politics, he became an active participant in the countercultural upheavals of the 1960s. At the end of the decade he was co-founder of an antitraditionalist movement called Mono-ha, which roughly translates as “school of things.”

Examples of Mr. Lee’s Mono-ha works here have an enigmatic, wry wit. A piece from 1969 called “Relatum” (Mr. Lee has used this word in the titles of most of his three-dimensional works) makes his concerns explicit. A length of rubber ribbon marked in centimeters like a tape measure is partly stretched and held down by three stones. A stretchy ruler will give false measurements, but are not all human-made measuring devices similarly fallible? Here was a parable for a time when authoritative representations of truth seemed increasingly unreliable to youthful rebels everywhere.

A work from 1971 consisting of seven found boulders, each resting on a simple square cushion on the floor, foreshadows Mr. Lee’s solution. The pillows add a certain anthropomorphic humor, as if the stones were incarnations of the legendary Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, whose minds expanded beyond human limits to embrace geological time. But more important, the seven rocks prompt meditation on our unmediated experience of things in time and space.

The problem is that in a museum setting it is next to impossible to experience stones unclothed by cultural, symbolic associations. We have seen too many rocks used as landscape ornaments and read too many poems about them. Looking at a “Relatum” from 2008, in which a boulder is placed in front of an 80-inch-tall steel plate that leans against the wall, the juxtaposition of nature and culture is too familiar, too formulaic, to be revelatory.

In paintings from the last four decades, Mr. Lee has made the brush stroke his primary device, often to optically gripping and lyrical effect. In the ’70s he pursued two approaches, always using just one color per canvas — usually blue, red or black.

In one series he used a paint-loaded brush to make horizontal rows of squarish marks one after another, each paler than its predecessor, as the paint was used up. He thereby created gridded fields of staccato patterning.

In other paintings he used wide brushes to make long, vertical stripes, dark at the top and fading toward the bottom. They give the impression of stockade fencing obscured near the ground by low-lying fog.

In the ’80s Mr. Lee loosened up his strokes and began to produce airy, monochrome compositions in a kind of Abstract Expressionist style driven not by emotional angst but by delight in existential flux. This period culminates at the end of the decade in canvases densely covered by squiggly gray marks that are among the exhibition’s most compelling.

From the mid-’90s on, Mr. Lee pared down his paintings, arriving four years ago at a particular modular form: an oversize brush stroke shaped like a slice of bread and fading from black to pale gray. He uses this device to punctuate sparingly large, otherwise blank, off-white canvases. Here, as with the stone and steel works, preciousness trumps phenomenology.

But something different and more exciting happens in a site-specific work that ends the show. In an approximately square room, Mr. Lee painted one of his gray-black modules directly on each of three walls. A surprising tension between the materiality of the paint and an illusion of space arises. The modules become like television screens or airplane windows, affording views of indefinite, possibly infinite space beyond the museum walls. It makes for a fine wedding of the real and the metaphysical.

"If a bell is struck, the sound reverberates into the distance. Similarly, if a point filled with mental energy is painted on a canvas (or a wall), it sends vibrations into the surrounding unpainted space...A work of art is a site where places of making and not making, painting and not painting, are linked so that they reverberate with each other."

"If a bell is struck, the sound reverberates into the distance. Similarly, if a point filled with mental energy is painted on a canvas (or a wall), it sends vibrations into the surrounding unpainted space...A work of art is a site where places of making and not making, painting and not painting, are linked so that they reverberate with each other."

- Lee Ufan

Korean at the forefront of Japan's modern art

Modernist pioneer Lee Ufan helped found a key postwar art movement in the homeland of his people's former colonizers

By EDAN CORKILL

For the last several years, Benesse Art Site on the island of Naoshima in the Seto Inland Sea has featured prominently in rankings of Japan's best tourist destinations.

|

Modern master: Artist and critic Lee Ufan stands beside one of his recent paintings at his home in leafy Kamakura, just south of Tokyo. Since moving to Japan from his native South Korea in 1956, Lee has become one of Asia's most important artists.

|

|

The publisher Rough Guides, for example, ranks the Kagawa Prefecture island's hotel and two art museums — set into a series of forested headlands — as the nation's sixth-most "must-see" attraction — ahead of Mount Fuji and the shrines of Nikko in Tochigi Prefecture.

This year, though, Naoshima's already superb facilities — operated by the Okayama-based publishing empire Benesse Holdings and a private foundation set up by its president — have been enhanced significantly.

Not only is the inaugural Setouchi International Art Festival, which kicked off July 19, centered on the island, but yet another museum has opened there — one, like most of Benesse Art Site's other facilities, that was designed by the world-renowned Tadao Ando.

In this case, however, the stately architecture is less significant than the fact of the museum's specific focus: It is devoted exclusively to the work of Japan-based South Korean artist Lee Ufan.

Lee, who turned 74 in June, occupies a unique position in the Japanese art world. An artist but also a critic, he first rose to prominence in 1969, when he played a key role in the formation of a modern-art movement that is still considered one of Japan's most important.

Mono-ha, which literally means the school, or movement, of "things," is actually less about the things an artist might create and more about the relationships in which he or she might place existing objects in order to convey tension or particular ideas. As Lee likes to say, he is equally interested in the "element that the artist makes" and the "element that is left unmade."

Yet, despite the prominence of Mono-ha in Japan's art history, Lee's recognition within the local art establishment has only come gradually. In the 1970s, Mono-ha was considered damaging and Lee a meddlesome troublemaker from abroad. It wasn't until 2001 that he was, more or less, brought into the fold when he was awarded the Praemium Imperiale — Japan's version of the Nobel Prize — for painting.

Lee first came to Japan in 1956, after spending just two months in an art university in Seoul. Since then he's primarily been based here, though as criticisms of his theorizing peaked 40 years ago, he started having annual sojourns to Europe, where he found a warm audience for his paintings.

Lee's artworks are mostly simple constructions. A typical recent painting sports a single, carefully applied brush stroke in blue — the product of a minute or two's intense concentration that is sustained, the painter says, by a single deep breath. Western viewers tend to interpret the paintings' simplicity as an expression of a particularly Asian aesthetic. Lee, though, insists they owe more to the Western Modernist tradition than anything else.

The paintings regularly fetch six-figure dollar sums at auction. A 1980 canvas with a series of vertical blue lines, for example, went for $410,000 at Sotheby's in New York in May this year.

|

| Lee Ufan in 1970 KIM S. S. |

With the opening of the new Lee Ufan Museum on Naoshima, dozens of Lee's paintings and sculptures now have a permanent home. Even more will be brought together at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in February, when a massive retrospective for the artist will be hosted by the museum.

When Lee is not in Europe, he lives with his Japan-born Korean wife in a studio- residence tucked into the hills of Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, just south of Tokyo. Their three daughters have left home — the oldest, Mina, is now a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama.

Lee was busy making new paintings in his studio when he took time out to talk to The Japan Times recently. Against a backdrop of vast white canvases punctuated by trademark thickly painted blue brush strokes, Lee discussed his art, the new museum, Mono-ha — and his complex relationship with Japan.

Congratulations on the new museum. What kind of venue did you want it to be?

I didn't want it to be a conventional museum, but more like a cave, something like a shelter, a place to escape to or to hide in. The plan Ando came up with is actually like that. For some people, it won't look like a museum. Some people might think it's a mosque, or a grave. That's fine. I wanted it to feel far removed from everyday life.

The museum is cavelike in that it is half underground. But, generally speaking, art museums are brightly lit, so you can see the art. The idea of an underground museum seems slightly contradictory.

These days, when we think of art, we immediately think of it being something that you look at. But it is actually only in the Modern period that this act of looking has been given such emphasis. Before then, there was more to it: myths, religion, social issues. People would know these stories and they would read them into the art. In other words, the act of appreciating art was completed in the mind.

With the arrival of Modernism that was stripped away, and you were left with the thing, the object, the artwork itself. I'm actually against that.

My art is of course visual, but I want people to imagine something more than what they see, more than is visible. So light is not so important.

You've mentioned your art, so I'd like to continue with that for a minute. You're saying that the idea is there is no meaning in the work itself, but that the work is a catalyst for imagining something bigger, something more abstract. I've read that you want viewers to come away from your work thinking about their connection with the world, the universe.

|

Underground art: A view of the cavelike Tadao Ando-designed Lee Ufan Museum that opened on June 15 on Naoshima Island in the Seto Inland Sea.

|

That's right. But when I talk about the external world, and its connection with the inner world, I am not talking about a connection with one's immediate surroundings. I'm talking about a connection to the world on a more transcendental level.

I don't make marks all over my canvases. I just touch them, maybe once. By doing that I can create a distinction between the areas of the canvas that have been marked and those that have not. And in so doing, I can get the viewer to imagine something deeper, a connection with the world on a more fundamental level — a sense of the existence of an underlying order.

Viewers in the West tend to look at your paintings and think their simplicity is characteristically Asian. How do you respond to that?

People often say that, but that is not the right approach. It is very ironic: Of course I was born in Asia, in a rural area, so I am Asian to the core, but the education I received was Western.

A minute ago I was being critical of Western Modern art, saying it has lost its narrative element, but, in a lot of ways, my work is a continuation of Modernism. It was artists such as Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich who simplified painting, reduced it to a concept. Then, in America, Minimalism went even further, reducing art to the very object itself.

But the irony is that when you reduce art to that level, then all of a sudden the viewer's attention shifts from the object itself to everything else. What kind of space is it in? What kind of time is it in? So the Minimalists ended up showing the opposite of what they wanted to show.

The aim of my work, from the outset, is to show everything else. The mark on the canvas is a trigger to get the viewer to imagine other things. This is where my Asianness might have played a role. By being born and raised in Asia, I might have been more in tune to an awareness of "everything else." After all, Asia has a monsoon climate, so there is a lot of rain. There's always things rotting and new life sprouting and, in the past, this gave rise to strong tendencies toward animistic beliefs. Asians are more likely to see themselves as living with nature, with the rest of the universe. So if you ask about the influence of Eastern thought on my work, then maybe that is one area where it happened.

Lee Ufan was born on June 24th, 1936, in Kyongnam, a poor mountain region in South Korea. At the age of 5 or 6 years old Lee Ufan went to study calligraphy, poetry and painting. He dedicated many hours to his studies including music comprehension in order to develop his artistic abilities. In 1953 he finished studying at the College of Kyongnam and entered the University of Seoul.

In 1956, at the end of his time at the university, he received recognition for being a talented artist especially with his works in oil painting. His stopped his studies soon after and moved from Korea to Japan where his uncle was living. There he picked up his studies at the university Takushoka in Tokyo. In 1958 entrance to the university allowed him to become a resident of Japan. He continued studying especially partaking in classes regarding philosophy at the Philosophy Department of the University of Nihon in Tokyo. At the same time he applied his methods of calligraphy at the exhibition "From Point". In 1961 he finished his studies in Philosophy and returned for a time to Korea. 1967 marked a major turning point when Lee Ufan opened his first major exhibition at the Sato Gallery in Tokyo. This began a long partnership between him and the Sato Gallery. He also participated in the hudge exhibition "Contemporary Art of Korea" at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo.

From 1971 to 1974 Lee Ufan taught a course at the School of Photography in Tokyo. In January he presented an installation at the Pinar Gallery of Tokyo. In May 1971 he participated in 10th annual japanese contemporary art show at the Metropolitan Art Museum in Tokyo and in September at the 7th Biennial in Paris where he was invited to represent Korea. For this occasion he represented the group for the first time in Europe. In November he presented a show at the Shirota Gallery of Tokyo. In 1971 he also taught a class about the Monoha movement along with an exhibit about the subject. In August 1972 he inaugurated his first show in Korea at the Myong-Dong Gallery in Seoul.

In 1973 the director of Tokyo's famous Yamamoto Takahashi Gallery, who Lee Ufan had previously met in 1960, organized an exhibit in his honor. Thus began a long collaboration between Lee Ufan and the Gallery. After travelling around the Occident he created his serious, "From Point" and "From Line," which were shown at the Tokyo Gallery. In July 1975 he commenced his second solo show at the Tamura Gallery. In the same year Lee Ufan was invited to participated in a large exposition entitled "Japan, Tradition and Gegenwart" in Dusseldorf and in "Japan Art Exhibition" at the Lousiana Museum of Modern Art. In November the Eric Fabre Gallery organized a solo Lee Ufan show in Paris.

In March 1977 he returned for a show at the Tokyo Gallery and in April he participated in the 13th Conference of Japanese Contemporary Art at the Metropolitan Art Museum of Tokyo. In January 1978 he had his first show at the Shirota Gallery in Tokyo dedicated to his etchings. In 1979, after an extendet stay in the Far East the Muramatsu Gallery dedicated a show to him. In June he participated in the 11th Biennial meeting of International Etching at the National Museum of Art in Tokyo where he received their top honor. In October the Kaneko Art Gallery of Tokyo organized an exhibit dedicated to Lee Ufan's drawings and watercolors. In the Spring of 1980 he returned for a joint show between Paris's Eric Fabre Gallery and Tokyo's Ueda Gallery. From 1982 to 1983 he exhibited at the Kaneko Art Gallery, the Tokyo Gallery and the Ueda Gallery (all in Tokyo).

From March to April 1985 he showed various sculptures at the Paris Gallery (formerly the Eric Fabre Gallery). In 1985 he participated in the Gallery opening at the Nakamura Michiko at the Kamakura Gallery in Tokyo. His show at Ueda Gallery in January 1986 presented a new mode and expression for the work of Lee Ufan, which was well received by the critics. In April, Lee Ufan became a professor at the University of Tama, a post he held with distinction for five years. In June 1986 the Shirota Gallery organized an exhibit of his "punte secche" works. At the same time the Tokyo Gallery presented his new works "From Winds." At the Musée National d'Art Moderne in the Centre Georges Pompidou of Paris, Lee Ufan participated in the March 1987 at the Exposition of Japanese Art of the XXth Century (Lee Ufan represented the Monoha Movement). In February 1987 he also exhibited some terracotta works at the Ueda Gallery in Tokyo. In 1988 Lee Ufan took part in a huge retrospective, containing 50 works dated from 1980 to 1987, from January 5th to February 11th at the Museum of Fine Art in Gifu. At the same time Lee Ufan set up a very important exhibit at Milan's PAC.

In February 1989 he presented a new series of etchings at the Shirota Gallery of Tokyo, that later became part of the exhibit at the Galerie de Paris. The same series later became part of the exhibit "With Winds", which was shown at the Ueda Gallery's contemporary art exhibition. In 1990, the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in Shibukawa dedicated a huge retrospective in his honor. Later, in May, the "With Winds '91 at Milano" was presented in Milano's Lorenzelli Arte Gallery. In 1993 another important retrospective took place at the Museum of Art in Kamakura. The next year Lee Ufan represented the Monoha Group at the "Japanese Art after 1945: Scream Against the Sky" exhibit. The same year two retrospectives began in his honor at the Fondazione Mudima in Milano and Seoul's National Museum of Contemporary Art (the first Korean recognition of Lee Ufan and his talent). In 1996, from the 18th of October to the 16th November, the Lisson Gallery of London exhibited Lee Ufan's first works in the U.K. From May 29th-July 5th, 1997, Lee Ufan exhibited works from 1993-1997 entitled "Correspondences" at Lorenzelli Arte Gallery in Milano and then later at the National Gallery of Jeu de Paume in Paris. In 1998 Frankfurth Stadelsches Kunstinstitut at the Stadtische Gallery organized another important retrospective. The next year Lee Ufan took part in the "Korean Art of 50 years" celebration at the Hyundai Gallery in Seoul.

In 2000 he took part in important exhibits at the Kroller-Muller Museum (Otterlo), Kunstmuseum (Bonn) and in Brisbane. Lee Ufan also participated at the group show "Anni '70 '80 '90" at the Lorenzelli Arte Gallery in May 2003. In 2005 he opened a retrospective at the Modern Art Museum in Saint-Estienne and in 2006 he participated at the Gwangju Biennial.

Lee Ufan was born on June 24th, 1936, in Kyongnam, a poor mountain region in South Korea. At the age of 5 or 6 years old Lee Ufan went to study calligraphy, poetry and painting. He dedicated many hours to his studies including music comprehension in order to develop his artistic abilities. In 1953 he finished studying at the College of Kyongnam and entered the University of Seoul.

In 1956, at the end of his time at the university, he received recognition for being a talented artist especially with his works in oil painting. His stopped his studies soon after and moved from Korea to Japan where his uncle was living. There he picked up his studies at the university Takushoka in Tokyo. In 1958 entrance to the university allowed him to become a resident of Japan. He continued studying especially partaking in classes regarding philosophy at the Philosophy Department of the University of Nihon in Tokyo. At the same time he applied his methods of calligraphy at the exhibition "From Point". In 1961 he finished his studies in Philosophy and returned for a time to Korea. 1967 marked a major turning point when Lee Ufan opened his first major exhibition at the Sato Gallery in Tokyo. This began a long partnership between him and the Sato Gallery. He also participated in the hudge exhibition "Contemporary Art of Korea" at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo.

From 1971 to 1974 Lee Ufan taught a course at the School of Photography in Tokyo. In January he presented an installation at the Pinar Gallery of Tokyo. In May 1971 he participated in 10th annual japanese contemporary art show at the Metropolitan Art Museum in Tokyo and in September at the 7th Biennial in Paris where he was invited to represent Korea. For this occasion he represented the group for the first time in Europe. In November he presented a show at the Shirota Gallery of Tokyo. In 1971 he also taught a class about the Monoha movement along with an exhibit about the subject. In August 1972 he inaugurated his first show in Korea at the Myong-Dong Gallery in Seoul.

In 1973 the director of Tokyo's famous Yamamoto Takahashi Gallery, who Lee Ufan had previously met in 1960, organized an exhibit in his honor. Thus began a long collaboration between Lee Ufan and the Gallery. After travelling around the Occident he created his serious, "From Point" and "From Line," which were shown at the Tokyo Gallery. In July 1975 he commenced his second solo show at the Tamura Gallery. In the same year Lee Ufan was invited to participated in a large exposition entitled "Japan, Tradition and Gegenwart" in Dusseldorf and in "Japan Art Exhibition" at the Lousiana Museum of Modern Art. In November the Eric Fabre Gallery organized a solo Lee Ufan show in Paris.

In March 1977 he returned for a show at the Tokyo Gallery and in April he participated in the 13th Conference of Japanese Contemporary Art at the Metropolitan Art Museum of Tokyo. In January 1978 he had his first show at the Shirota Gallery in Tokyo dedicated to his etchings. In 1979, after an extendet stay in the Far East the Muramatsu Gallery dedicated a show to him. In June he participated in the 11th Biennial meeting of International Etching at the National Museum of Art in Tokyo where he received their top honor. In October the Kaneko Art Gallery of Tokyo organized an exhibit dedicated to Lee Ufan's drawings and watercolors. In the Spring of 1980 he returned for a joint show between Paris's Eric Fabre Gallery and Tokyo's Ueda Gallery. From 1982 to 1983 he exhibited at the Kaneko Art Gallery, the Tokyo Gallery and the Ueda Gallery (all in Tokyo).

From March to April 1985 he showed various sculptures at the Paris Gallery (formerly the Eric Fabre Gallery). In 1985 he participated in the Gallery opening at the Nakamura Michiko at the Kamakura Gallery in Tokyo. His show at Ueda Gallery in January 1986 presented a new mode and expression for the work of Lee Ufan, which was well received by the critics. In April, Lee Ufan became a professor at the University of Tama, a post he held with distinction for five years. In June 1986 the Shirota Gallery organized an exhibit of his "punte secche" works. At the same time the Tokyo Gallery presented his new works "From Winds." At the Musée National d'Art Moderne in the Centre Georges Pompidou of Paris, Lee Ufan participated in the March 1987 at the Exposition of Japanese Art of the XXth Century (Lee Ufan represented the Monoha Movement). In February 1987 he also exhibited some terracotta works at the Ueda Gallery in Tokyo. In 1988 Lee Ufan took part in a huge retrospective, containing 50 works dated from 1980 to 1987, from January 5th to February 11th at the Museum of Fine Art in Gifu. At the same time Lee Ufan set up a very important exhibit at Milan's PAC.

In February 1989 he presented a new series of etchings at the Shirota Gallery of Tokyo, that later became part of the exhibit at the Galerie de Paris. The same series later became part of the exhibit "With Winds", which was shown at the Ueda Gallery's contemporary art exhibition. In 1990, the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in Shibukawa dedicated a huge retrospective in his honor. Later, in May, the "With Winds '91 at Milano" was presented in Milano's Lorenzelli Arte Gallery. In 1993 another important retrospective took place at the Museum of Art in Kamakura. The next year Lee Ufan represented the Monoha Group at the "Japanese Art after 1945: Scream Against the Sky" exhibit. The same year two retrospectives began in his honor at the Fondazione Mudima in Milano and Seoul's National Museum of Contemporary Art (the first Korean recognition of Lee Ufan and his talent). In 1996, from the 18th of October to the 16th November, the Lisson Gallery of London exhibited Lee Ufan's first works in the U.K. From May 29th-July 5th, 1997, Lee Ufan exhibited works from 1993-1997 entitled "Correspondences" at Lorenzelli Arte Gallery in Milano and then later at the National Gallery of Jeu de Paume in Paris. In 1998 Frankfurth Stadelsches Kunstinstitut at the Stadtische Gallery organized another important retrospective. The next year Lee Ufan took part in the "Korean Art of 50 years" celebration at the Hyundai Gallery in Seoul.

In 2000 he took part in important exhibits at the Kroller-Muller Museum (Otterlo), Kunstmuseum (Bonn) and in Brisbane. Lee Ufan also participated at the group show "Anni '70 '80 '90" at the Lorenzelli Arte Gallery in May 2003. In 2005 he opened a retrospective at the Modern Art Museum in Saint-Estienne and in 2006 he participated at the Gwangju Biennial.

A modest encounter in line with ecstasy is how renowned Korean born artist

Lee Ufan,

75, describes his unrestricted and infinite art. Ranging from painting

and sculpting to writing and philosophy, Ufan’s endeavors are endless

and groundbreaking, as he penetrates the contemporary art world through

his spiritual ways.

But that is not what makes him unique.

Rather it is his desire to showcase “the jargon of the universe” as well

as his methodology of linking words and art as one – an ongoing

dialogue and unity between art forms and people.

In an exclusive interview for

GALO,

Ufan brings light to his art, explains his love for literature, and

tells us his most memorable moment at the Guggenheim Museum in New York,

whilst preparing for his ongoing

Marking Infinity exhibition.

From my childhood, I learned to

draw and paint. But as I grew older, I started showing more interest in

literature, to the point where I wrote my own novels. Meanwhile, I also

took [an interest in] music, on which I worked with deep concern, so I

once wanted to become a composer. It is due perhaps to my countryside

background that I was slightly timid, which made me lean more toward art

instead of other areas.

GALO: Why did you decide to pursue this interest professionally?

LU: It was probably the difficulty of

language that stood between me and my willingness to achieve something

in literature, and naturally, art became my main activity of concern. I,

of course, chose visual art out of all other art forms, but the

imaginative power that generated a force of drive in working at it

sustained me throughout my life as an artist.

GALO: In your biography it says that you studied painting

at the Seoul National University’s College of Fine Arts for two months,

at which point you transferred to Nihon University in Tokyo and majored

in philosophy. Why did you leave your studies in Korea for those in

Japan, and why did you not continue studying the Fine Arts, while in

Japan, and instead chose philosophy?

LU: The choice to study art in university

was enforced by my entourage, rather than my own will. There it became

tedious. During those days, I had an order from my father to deliver

some oriental medicine to my uncle who was at the time suffering from a

serious illness. As I arrived in Japan, I was convinced by him to study

in Japan. My compliance with the recommendation took me to the

philosophy department of a university, where I fell in love with reading

and contemplation.

GALO: Has this elicited a challenge for you within the art community?

LU: It was indeed my knowledge and groping

in philosophy that allowed me to sublimate my thinking into an

expressive form in art, but there is also the factor of perception that

directs and projects my thinking into the world. It certainly requires

the strength of learning, bodily practice and understanding, to command a

respectable work of expression.

GALO: Has your knowledge of philosophy helped you with

your artwork? Has it helped with your creativity and understanding of

art?

LU: If a work of art goes just as far as

[an] extent of its expression of [a] idea per se, there is simply no joy

in working. My learning and thoughts on various philosophèmes were for

certain of a great importance in my inquiries into higher and deeper

dimensions. But what is more crucial in such [a] stance of an artist is

not [very] much ingrained in the idea itself, but the attitude which has

to be philosophical.

GALO: Is there a particular philosopher who you most admire and that has inspired you?

LU: Among the thinkers I was influenced by,

there are: Heraclitus, Lao-tze and Zhuangzi, as well as Kant,

Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty and Kitaro Nishida.

GALO: What does art mean to you?

LU: Art is the spiritual provision that enlightens one on the next level of sublimity of life.

GALO: Describe your creative process. What do you like to do before you start working on a project? During? Any rituals?

LU: I collect my senses calmly and draw

long, deep breaths for quite a while, then gather all the equipment

needed for working, which raises the level of concentration.

GALO: What materials do you usually like to use when painting? When sculpting?

LU: For painting, there are custom-made

canvases, colors, brushes, as well as my hands, which in their

predetermined plan are all appositive. As for my sculptures, I use

natural stones that are commonly existent around us, and steel plaques,

rendering them in a term of relationship. And it is in such

relationships between the industrial and the natural that I would like

the spectators to perceive, [affectionately] the infinity.

GALO: How does it feel to have a retrospective of your

artwork showcased at one of the most prestigious museums in the world –

the Guggenheim?

LU: One memorable point of exhibiting at

[the] Guggenheim was the entrance leading to the interior that creates a

curving upward slope, a trait that distinguishes it from the

conventional White Cube. The challenge was to make sure that my works

[would] blend into this particular environment. However, such

instability was to be availed of, and there exists direct sensation that

can be [awakened] closer to our bodies, making it a very [stimulating]

exhibition.

GALO: I read somewhere that last October you were picking

out stones in Long Island, especially around the Hamptons area, for

your present exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. What

specifications were taken under consideration when you were selecting

them? What were you envisioning?

LU: The point is definitely not to exhibit

some handsome looking stones that are pleasing to see. The standard of

choice was based on how neutral they looked as a natural being. I look

for the sense of temporality that it holds as an existential marvel,

radiated from stones. Perhaps upon occasions, stones and plaques could

come into my mind after a certain concept occurs to my awakening, or it

could be the concept that sets up the ground for a new work. All these

call upon each other to be evoked.

GALO: I believe that there are approximately 90 of your

works on display at the Guggenheim right now, ranging from your

paintings and drawings to your sculptures. Is there one that you would

say is your favorite or perhaps one that has an interesting story behind

it that you feel especially connected with?

LU: There is a raison d’être [reason for

being] and a story for every work that I do. But if I were to pick one

example, it would be the wall painting, the working duration and the

amount of work for which was the most challenging amongst others. One

staff member, from the installation team, called the room “lofty” with

the hands posed on the chest.

GALO: What do you hope that viewers will take away by

viewing your diverse artwork at the Guggenheim? Is there a particular

message that you strive to get across through your art?

LU: I hope that the spectators will try to

sense the work with all parts of their body before attempting to give

personal interpretations right away. In today’s [world], it is easy to

consign the importance of works of art and their visual aspects to

utterance and communication. This is of course not harmful to the nature

of art, but it is my personal belief that an exhibition would radiate a

vibrating resonance to the people who perceive it: between body and the

space.

GALO: You have written a few books on your artwork and

philosophy, including poetry. Why is this form of expression of

importance to you? Does it derive from your love of literature and your

past desire to study it while in college?

LU: I still do hold [admiration for] the

power of literature. That means that my works are poetic

representations. If I decide to write, rather than produce artwork, it

is because [of] the need to choose words over visual art forms, or

because I think that words are better suited for the expression

conceived. But in either case, art for art’s sake, or literature for

letter’s sake, is not relevant to such statement.

GALO: You were one of the founders and the leader of the

Mono-ha earth-art movement. I understand there is an interest and idea

of blending nature and art together in it. Could you explain what the

Mono-ha movement is in relation to art?

LU: One would be mistaken if Mono-ha was

taken as integration between nature and art” — it was an endeavor to

deconstruct modern art. In other words, it wasn’t absolutism of the

so-called “almighty,” but a movement that contains the self and connects

what is not made. As a result, this sort of thought leans toward more

ecological conception in criticizing mass-production cultures.

GALO: In the past you were fighting as an artist and a

political activist for various issues, including the approach to

de-westernization. Is there anything that you are still fighting for

presently?

LU: In my youth, I stood up against the

military regime of (the third and fourth – translator’s note) Korea

Republic and took part in reunification movements, and even composed a

few words for them and participated in theater pieces. This has not so

much in relation with the concept of de-westernization, but rather with

overcoming the modern in the most global way possible. This thought has

certainly had a lot of obstacles to surmount. Naturally my focus became

concentrated more on the aesthetic dimensions of modernity than on

socio-political ones. Every now and then, I am received as a blind

supporter of Orientalism, but this is not true: I’d say I am neither

Orientalist nor Europeanist, but am what I am as Lee Ufan.

GALO: Describe your art in three words.

LU: Modest, encounter, ecstasy.

GALO: You’ve been creating art for many years. What inspires and motivates you to produce new artwork?

LU: One would always need the power to

perceive objects or the world in new ways, as well as ideas and courage

that can enable [one] to sublimate it.

GALO: Do you believe that artistic creativity is something that one is born with or something that can be learned?

LU: Artistic sensitivity exists in everyone

in one form or another. It sometimes reveals itself through creativity

brought about by a certain moment of opportunity. Normally people do get

moved by the beauty of a flower or a high mountain, but such

appreciation does not necessarily expand to another generalized [and]

sustained dimension.

GALO: How do you perceive the art of today in relation to

that of classical artists and that of your own? Is there something that

you particularly dislike?

LU: All artists who stand on the fine

borders of today are great in their own right. It was relatively

uncomplicated, and very often credulous, to create a new current and to

become massively prevalent in the art world; whereas today, artistic

motives and styles are extremely multifarious, in other words, it is a

time of infinite variety. On the contrary, to making a point on artists,

it is the sloppy curators who put out tag lines or prematurely

determined propositions.

GALO: Many people say that art is universal and holds no

boundaries or lines that divide it from country to country. Do you

believe this statement to be true? Or do you think that there are

certain differences that cannot be understood without at least a basic

knowledge of a country’s history and culture?

LU: I have frequented many different

geographical locations thus far, where I have also as a result

experienced difficulties and hardships. Perhaps with this fact acting as

a cause, anything in the nature of nationalism, racialism, and even

globalism doesn’t interest me at all. As historic thinkers like Kant

would affirm, art has to, first of all, resolve through the self. At the

same time, considering my background of youth, my memories from those

days have gotten into [my] DNA. One should however note the risk of

dogmatism, which can easily come about and be dangerous, if one attempts

to rationalize it.

GALO: In past interviews, you mentioned that you do not

wish to follow the rules of the modern art world today because you do

not want to be constrained by them; you want to be free. Could you

elaborate on this?

LU: Even as one criticizes the modern, it

is harbored and lurks everywhere in my environment. This means that

critique toward Modernism redirects itself onto the person criticizing,

but at the same time it is a manifestation of one’s own desire for the

unknown of the future. If Modernity gives us the world of the internal

via Ego, our contemporaneity proposes the world of the external through

the relationship between the Self and the Other.

GALO: You have described your art as “the art of encounter.” Please explain what you mean by this.

LU: If a work of art is to be seen and

determined as a solidified meaning, it is simply not fun at all. The

circulation of meaning should be allowed to flow in different vectors,

like in a room with its two windows wide open on each side. Similarly in

work-viewer relationship, there must be a sense of vibrating resonance

of encounter. Encounter then, is a sort of shaking, as well as [a] new

birth.

GALO: Is there one museum, gallery or country that you have not yet exhibited at, but wish you could? If yes, which one and why?

LU: There is plenty. But oddly enough,

something tells me that I am longing to open an exhibition [on] some

anonymous planet. By this, I want spectators to respond to my

exhibitions, so that they see a glimpse of the jargon of the universe.

GALO: What are your artistic plans for the near future?

LU: My next goal is to sublimate my present works to a higher platform of dimension.

GALO: Lastly, what piece of advice would you give to

those who are just starting out and trying to make a difference in the

art world today?

LU: The grand tendency of today’s art world

is to contradict the idea of ‘body’ and ‘time.’ My interest is in

looking at how it will develop.

The Breath of a Margin

The artworks I create are all tapestries of intimate

breathing between me and the world. Therefore, seeing is not the

confirmation of an object but a quiet concert of breathing between the

work, the world, and the viewer.

—Lee Ufan

Blum & Poe is pleased to present the first West-coast

U.S. gallery exhibition of internationally acclaimed artist Lee Ufan.

Achieving critical praise at the 52nd Venice Biennale for his

exhibition,

Resonance at the Palazzo Palumbo Fossati in 2007,

Lee has held major retrospectives at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of

Belgium (2009), Yokohama Museum of Art (2005), Musée d’Art Moderne de

Saint-Étienne Métropole (2005), Kunstmuseum Bonn (2001), and Galerie

Nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris (1997). Lee has received many

prestigious awards including the Praemium Imperiale prize in painting in

2001 and UNESCO Prize in 2000. He has served as a visiting professor at

the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and professor of art at Tama Art

University in Tokyo from 1973 to 2007. A collection of Lee’s writings

was recently published in

The Art of Encounter (Lisson Gallery, 2008).

The show will present a historical survey of paintings and

works on paper from 1974 to the present that include the artist’s key

series,

From Line, From Point and

With Winds, which demonstrate the development of a breath-like repetition of a gestural act over time. The exhibit will also showcase

Dialogue

(2007–present), a series of recent large-scale oil on canvas paintings

together with three sculptural installations (including one displayed

outdoors) from his

Relatum (2008) series that combine natural

stones with industrially-produced steel plates to explore perception as a

symptom of both the materiality and immateriality of space.

Lee Ufan’s career encompasses a spectrum of activity ranging

from artist, philosopher, and poet. Born in Korea in 1936 and emigrating

to Japan in 1956, Lee obtained a degree in philosophy at Nihon

University in 1961 and became widely known as the key ideologue of the

critical late-1960s Japanese artistic phenomenon, Mono-ha (School of

Things). In dialogue with post-minimalist practices, Lee’s work

developed out of Mono-ha’s tenet to explore the phenomenal encounter

between natural and industrial objects such as glass, rocks, steel

plates, wood, cotton, light bulbs, and Japanese paper in and of

themselves arranged directly on the floor or in an outdoor field. What

has distinguished Lee is his refined technique of repetition as a

studied production of difference developed over time in both his

painting and sculptural practice.

A key device that guides Lee’s working method is the notion

of lived time (the perpetual passage of the present) through the flux

between the visible (actual) and invisible (virtual) both in the

production and the reception of his work. This process begins with the

rhythm involved in the preparation of each work: the strict choice of

materials, the consciousness of each breath and bodily stance, and the

strict positioning and application of each material element. Lee’s

Relatum

series come out of a rigorous search for the precise stone to juxtapose

industrially-produced, weathered steel plates, which are at times

scattered around the floor to form a capacious field, leaned toward each

another like an embrace, or propped against a wall with the steel

acting as a screen-like shadow bringing forth the stone’s bodily

profile. This sense of movement is also carried in his paintings, which

begin by mixing mineral powdered pigments (cobalt blue, orange, and more

recently blue-grey) with glue and choosing an appropriate brush to

apply onto a large white canvas. Through the continuous repetition of a

gestural act in

From Line, From Point, and

With Winds,

Lee loads his brush with mixed pigment and begins applying a single

linear stroke or point onto the canvas one by one until the pigment has

faded and repeats this process in an orderly fashion. The empty space

deliberately left on the white canvas or wall seen especially in his

most recent

Dialogue series, as well as the light, air and shadows that fall in and around his objects in

Relatum

are integral to the work’s breath-like contraction and expansion of

matter, embodied for example in the thousands of years of erosion the

stone has endured and passes forth to our present moment.

Lee has thus followed what one might call an ethics of

duration: activating a passage for the viewer to perceive what lies

before and around us, even the objects and spaces that are invisible to

the eye, as co-existing entities that are brought together to form an

affective relationship. Lee has named his practice the art of margins,

or

yohaku, the resonance between the visible and not visible,

the made and unmade, that permeates and reverberates one’s surroundings

like a resounding echo or tidal flow. In the artist’s words,

Yohaku (margins) is not empty space but an

open site of power in which acts and things and space interact vividly.

It is a contradictory world rich in changes and suggestions where a

struggle occurs between things that are made and things that are not

made. Therefore, yohaku transcends objects and words, leading people to silence, and causing them to breathe infinity.

One can trace this idea of

yohaku back to 1969, when

Lee staged an ephemeral work consisting of three large sheets of

Japanese paper fluttering in the wind, entitled

Things and Language

outside of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and later placed directly

on the gallery floor as part of the “Ninth Contemporary Art Exhibition

of Japan.” The ephemerality of this event (a happening) brings to light

both the modernist critique of the permanence of the work of art as well

as the object as a symptom of the physicality of its surrounding

environment, issues also fundamental to post-minimalist practices in the

West. In direct response to the eschewal of traditional conceptions of

sculpture in particular, Lee envisions the radical destruction of the

art object as an objectified medium for signification and expression,

and rather focuses on seeking an open, relational structure that

activates the limits of our senses and perception. For example, in

Phenomenon and Perception B

(1968) presented later that year at the “Trends in Contemporary Art” at

the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, a natural stone was placed

on a plate of “broken” glass to create the illusion that the stone had

been dropped onto the plate, capturing the discord between chance and

intention (a nod to and reversal of Marcel Duchamp’s

The Large Glass). Later renamed

Relatum

(the title given to all of his sculptures up until the present), Lee

began exploring the phenomenal encounter between organic and industrial

materials and its surrounding environment. As he states, “A work of art,

rather than being a self-complete, independent entity, is a resonant

relationship with the outside. It exists together with the world,

simultaneously what it is and what is not, that is, a relatum.” Here we

see how

yohaku has its direct roots in the

Relatum

experiments by re-conceiving the breakdown of the object as a durational

form of co-existence between the actuality and potentiality of elements

(i.e. ephemerality, chance vs. intention, and relational structure).

This idea of duration as a form of ethics is developed not only through

his artistic practice, but also in his writings. It was during this time

when Lee began publishing his ideas in a series of now seminal

articles, which were subsequently compiled into a book entitled,

Deai o motomete (The Search for Encounter) (1971).

Lee’s works thus operate as a process of perceiving a

perpetually passing present and opens the materiality of the work beyond

what is simply seen. Like a shadow, the works make visible the passage

of time it profiles. And through this synthesis, each work presents a

temporal structure that mediates a phenomenological encounter among

viewer, object, and site. This cycle of duration can thus be seen as a

mode of eternal recurrence that bind the seemingly opposing elements of

destruction and continuity, detachment and relationality, finitude and

infinite expanse present in Lee’s oeuvre as a solemn affirmation of

life.

–Mika Yoshitake

7 comentarii:

By Karlyn De Jongh and Sarah Gold

Painter, sculptor, writer and philosopher Lee Ufan (*1936, South Korea) is about Encounter. He focuses on the relationships of materials and perceptions; his works are made of raw physical materials that have barely been manipulated. Lee Ufan's often site-specific installations centralize the relationship between painted / unpainted and occupied / empty space. With his work, Lee Ufan addresses Encounter in its relation to life in general, not only in its relation to art. Therefore, according to Lee Ufan, having an encounter with his work is not just an encounter with his work: it is an encounter with the world. This is his idea of ‘being there’ at a particular space at a certain moment. Through the relationship between the works and the spaces in which they are placed, he invites the viewer to experience "the world as it is."

Lee Ufan was born in Korea and went to Japan when he was nineteen years old. During his life, he has been in many different countries and says he feels like a foreigner each time - wherever he is. “I am a stranger, and due to this, my ability to communicate is disrupted: this in turn brings discomfort, and leads to misunderstandings. I have lived under these circumstances for a long time: that is ‘encounter’ for me. […] Encounter is dealing with others; it is a very simple thing.” Having an encounter, happens every time when experiencing something that is outside of yourself. It starts in the very moment of contact – when you meet other people, when you look at the moon or at a building. Facing other people is simultaneously a passive and active encounter: you encounter the other, but the other encounters you too. The artist explains that the concept of Encounter is not necessarily about verbal communication. Neither is it about the differences in meaning between East and West.

Lee Ufan prefers to start from ‘normal’ things. Encountering something is dealing with ‘Otherness’. Lee Ufan remarks that humans usually want to perceive and understand the other with all the knowledge they have gained. “But in reality, you feel a distortion, a gap between knowledge and reality. You see the separation in between them and you start becoming aware of the unknown.” The artist gives the example of encountering a stone. “We can understand a stone with knowledge, by analyzing it. But when you see a stone, you do not know at all; we often have the feeling “what is that?” This is not simply “I do not know”; rather, this is an unknown character. An unknown character always invites me to learn more about things in one or another way.”

The unknown of the encounter with the other, is in the relation. You experience the relation between yourself and the other. For his work, Lee Ufan therefore often uses the combination of materials that centralize this ‘relation’ and create the feeling of distortion – the feeling of ‘what is that?’. For example, the combination of a steel plate and a stone, which is a combination between nature and something that is created by human beings in an industrial society: “A stone is not man-made. Stones lay around anywhere by mountains and rivers. Whether you are from Africa, from Paris, or from America, everybody knows; stones are from nature, and a steel plate is industrial. I have thought about what the viewers can feel and see. I try to make the viewer feel the combination of things, those made by our industrial society and those that are from nature.” With the combination of these materials Lee Ufan creates space. “Normally, in modern art, the work is the object itself. My art is not a painting and not a sculpture. I don’t make just objects, I create space: ‘Ba’ and ‘being there’. What is going to happen with the stone and the steel plate, what I can feel with them being together, that is very important.” Being influenced by his surroundings, means that Lee Ufan’s work is decided in relation to a particular location, a particular space. “Normally fine spaces exist everywhere, be they a mountain, a riverside, a gallery, a home, etc. But this is very complex, and raises many difficult questions. That is why the way my work relates to the space in which it will be presented is the most important aspect I consider. But the truth is, anywhere is fine. I do not place my completed work on the spot; my work is made ready through its relation with the space where I want to place it. The relation itself is infinite.”

One learns with age and acquires more knowledge, but even Lee Ufan, having seen many stones, steel plates and having created many paintings, still has encounters when he makes a work. “When I make a painting, I also have small encounters: a feeling of subtlety, questions and other things come up. ‘Encounter’ is non-continuous: always changing. It is important that it is a passive and active thing. That is the reason why I want to paint a multitude of seemingly the same paintings, endlessly. For me, perfection does not exist, nor can a work be controlled one hundred percent. I cannot know what will happen at the moment I start working in a certain location.” When making work, Lee Ufan says he uses his body as a channel. The body is influenced by its relation to the surrounding: whether it is cold outside, whether the work is made in a large or a small space. Being influenced by his surroundings, means that Lee Ufan uses much more than only his knowledge to create art. “I paint my relation to the outside naturally through this intermediate connection. My body is not mine, and my body is not just inside or outside, it is in between.” Lee Ufan remarks that this understanding of the body comes from the Asian understanding that ‘body’ is not just ‘myself’, but that it includes the relations with the outside. In its contact with the outside, the body becomes something ‘in the middle’, or ‘in between’.

Lee Ufan prefers what he calls a ‘fresh encounter’, one that is not colored by previous knowledge or expectations of how something ‘should be’. When he came to visit Palazzo Bembo to look at his space in December 2010, Lee Ufan told us an anecdote about an exhibition he once had in France and how he used to be when he was young. To make his work for this exhibition, he traveled the country in search for a stone. Looking for a stone, however, Lee Ufan admits he somehow could not find any – until he saw one in what appeared to be a Japanese garden. Later, he realized that at that time he was still too much influenced by his culture: a stone from the mountains in France did not feel like a stone to him; he was looking for something he knew; other stones did not feel ‘right’. Nowadays, Lee Ufan chooses stones that are from the region or country where the work is exhibited – like the Carrara Marble we have in Palazzo Bembo. The feeling Lee Ufan described in the anecdote is exactly the feeling he wants to distance himself from. He wants for him and other people, to have a fresh encounter with the world around him. Lee Ufan explains: “If we do not know about Christianity and Greek mythology, we cannot understand western art. When I just look at the painting itself, I cannot understand it at all; it requires a broad depth of prior knowledge. Modern art also has many rules and artists are creating works by using those rules. I want to be different from those rules; I want to be free. This is why I want to have reactions from African, American, European and Asian people encountering my work like, “Wow, what is it?” The meaning does not matter, but I want to have these fresh moments; they are very important for me.”

Am o mulțime de bucurii și emoții în mine, sunt claritate, am fost fericit cu căsnicia mea, până când soțul meu nu a început să asculte bârfe despre mine nefiind credincioși cu promisiunile noastre conjugale, am încercat să-l înțeleg că sunt bârfe și minciuni, dar a pierdut dragostea, încrederea și încrederea în noi. Așa că am devenit cupluri neplăcute și apoi am depus divorț, mai târziu, ne-am despărțit. ani după divorțul nostru, am încercat să trăiesc o viață normală fără el, dar nu am putut, așa că am început o căutare despre cum să-mi revin fostul soț, apoi m-am referit, BaBa ogbogo un bărbat grozav și extrem de spiritual care a aruncat un dragoste vrăjește asupra mea și m-a făcut EX-ul meu să se întoarcă la mine. Sunt copleșit, așa că îi las contactul aici pentru cei care au probleme de relație și căsătorie, așa că poate ajuta cu lucrări grozave. E-mail: greatbabaogbogotemple@gmail.com. Sau numărul lui de WhatsApp ... +2349020168697. Luați legătura cu el, vedeți cât de mare și puternic este. De asemenea, ajută în aceste probleme ...

(1) Opriți divorțul.

(2) Barrenness End.

(3) Noroc vraja.

(4) Vraja de căsătorie.

(5) Scapă de probleme spirituale.

Bună ziua tuturor sunt aici pentru a mulțumi DR ODION că m-a făcut din nou fericit, logodnicii mi-au părăsit când urma să se căsătorească după 2 luni. Și am fost atât de frustrat că am avut o zi proastă de-a lungul. până când am fost online și voi afișa o recenzie a cuiva care postează o mărturie a unui doctor numit ODION pe care l-am contactat de fapt și el m-a asigurat că nu ar trebui să-mi fac griji că prietenul meu va reveni odată ce va termina cu munca sa în 24 de ore . din păcate, întâlnesc o celulă pe telefonul meu și a fost iubitul meu, iar el mi-a spus că îi pare rău că ar trebui să-l iert că se întoarce pentru ca noi să fim împreună. Mulțumesc lui DR ODION pentru munca sa amabilă. Dacă aveți aceeași problemă îl puteți contacta prin WhatsApp +2349060503921 sau prin e-mail (drodion60@yandex.com)

Bună ziua tuturor sunt aici pentru a mulțumi DR ODION că m-a făcut din nou fericit, logodnicii mi-au părăsit când urma să se căsătorească după 2 luni. Și am fost atât de frustrat că am avut o zi proastă de-a lungul. până când am fost online și voi afișa o recenzie a cuiva care postează o mărturie a unui doctor numit ODION pe care l-am contactat de fapt și el m-a asigurat că nu ar trebui să-mi fac griji că prietenul meu va reveni odată ce va termina cu munca sa în 24 de ore . din păcate, întâlnesc o celulă pe telefonul meu și a fost iubitul meu, iar el mi-a spus că îi pare rău că ar trebui să-l iert că se întoarce pentru ca noi să fim împreună. Mulțumesc lui DR ODION pentru munca sa amabilă. Dacă aveți aceeași problemă îl puteți contacta prin WhatsApp +2349060503921 sau prin e-mail (drodion60@yandex.com)

CASTER DE SPORT PROFESIONAL, CARE VĂ POT AJUTA CU Vrăjitorul de iubire pentru a VĂ EXPUNE EXPLOȚIA DRAGOSTEI ÎN URGENȚĂ DUPĂ DESCĂRCARE / DIVORȚIE ÎN CAZ DACĂ SITUAȚIA DUMNEAVOASTRĂ ESTE NECAPĂ! CONTACT: DR. ODION (drodion60@yandex.com) ESTE CERTA CEL MAI BUN DE VÂNZARE ONLINE ȘI REZULTATUL său ESTE GARANTARE 100% ..

După 3 ani într-o relație cu iubitul meu, iubitul meu a început să iasă cu alte fete și să-mi arate dragoste rece, în mai multe rânduri amenință că s-a despărțit de mine dacă îndrăznesc să-l întreb despre afacerea lui cu alte fete, am fost în totalitate devastat și confuz până când un vechi prieten de-al meu mi-a povestit despre o cască de vrăji pe internet DR. ODION care ajută oamenii care au relația și problema căsătoriei prin puterile dragostei Vrăji, La început m-am îndoit dacă așa ceva există vreodată, dar am decis să încerc, atunci când îl contactez, mi-a spus tot ce trebuie să fac și am făcut. și m-a ajutat să arunc o vrajă de dragoste și în 48 de ore, prietenul meu s-a întors la mine și a început să-mi ceară scuze, acum a încetat să mai iasă cu fetele și este cu mine pentru bine și pentru real. Contactați această Casă de mare vrăjire pentru relația dvs. sau problema dvs. de căsătorie.

Iată contactul său ..

APEL / WHATSAPP: +2349060503921

EMAIL: (drodion60@yandex.com)

Trimiteți un comentariu