A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

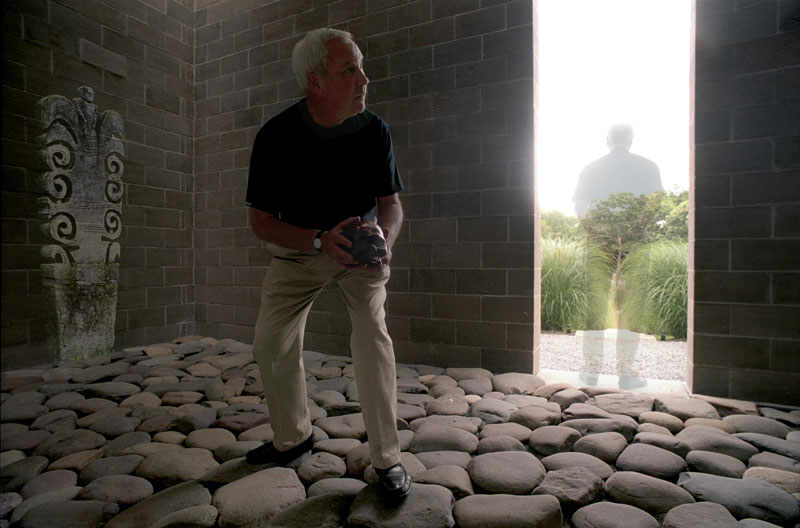

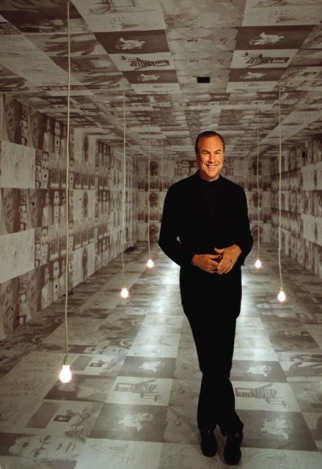

It can truly be said that Robert Wilson does it all. He directs plays and operas, meaning he comes up with a concept and follows through to each movement. He designs scenery and lighting, meaning he visualizes not only the people on the stage but also their environment. He writes the text for plays and operas, meaning he creates the original ideas that motivate every action and thought that is presented. He paints and sculpts and has worked with sounds. He has a degree in architecture and understands business administration. He seems to have a hand in every aspect of theatrical life! He even founded the Watermill Center [where he was photographed above] as a laboratory for performance and research. He is the very definition of “forward-looking,” and pushes the envelope wherever he lands.

While he may not be unique and others may also multi-task, Wilson is the one who has risen to the top and commands attention from all who present and appreciate the business.

To learn more and see other photos, visit his website.

In the fall of 1990, Wilson was giving Chicago his version of Alceste by Gluck, featuring Jessye Norman in the title role. He was kind enough to accept my invitation for an interview, so we met in a dressing room backstage at the Opera House after a rehearsal . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You have just come from a long rehearsal. Do you do everything in the rehearsals, or is there anything that you leave for the performers to do on the first and subsequent nights?

Robert Wilson: It depends on the performer and on the situation. The situation is always different with an audience, so some performers work best when they only mark during rehearsals, and you know that they’re going to do more when there’s a public. Some give you everything in a rehearsal. Everyone has a different rhythm. Sometimes they start out great and get worse. Sometimes they start out not so good and get better. And sometimes they start out good and remain good!

BD: Do you try to mold them so that every movement is yours, or do you allow them any kind of freedom?

RW: No, no, no, no. It ultimately has to be theirs. The movements and gestures are choreographed, but ultimately the performer has to do them, so they must be theirs. They’re no longer mine. It’s like giving away your children; you have to let them grow up and be on their own.

BD: How much molding do you do, and how much allowing do you do?

RW: Oh, quite a bit. It’s like when you spend certain times gardening; you plant seeds and you try to put each one of them equal distance apart. But when they grow up, you see that one grows a little bit this way and one grows a little bit that way. So that’s the nature of the game, and that’s what makes the line beautiful.

RW: Oh, quite a bit. It’s like when you spend certain times gardening; you plant seeds and you try to put each one of them equal distance apart. But when they grow up, you see that one grows a little bit this way and one grows a little bit that way. So that’s the nature of the game, and that’s what makes the line beautiful.BD: Does the growing continue in the second and the fifth and the eighth performance?

RW: It does, and I have people that watch the performances just to give notes because it’s always helpful to have someone on the outside looking at what one’s doing. That’s really the function of a director. A director is someone who’s outside looking at the situation, and is there to help the performer be at his best.

BD: [With a sly nudge] You have spies? [Laughs]

RW: [Matter-of-factly] No, I have an assistant who watches each performance and gives notes.

BD: So you turn over the reins to the assistant, then?

RW: Yes, exactly.

BD: Do you allow the assistant to move anything around or just keep them charting the course that you have set?

RW: If a new singer would come in, I think you’d leave that assistant in charge to make a decision as to what he thinks is best at that moment.

BD: Let me go back one step farther. Do you come to the first rehearsal with all of your ideas in your head, or do you work with what you have and then modify your own ideas to fit your conception, their conception, and the growing conception?

RW: It depends on the production, but in general I would say in the last years I come to rehearsal with very few ideas in mind. When I first started working in the theater, I used to think that I had to do a lot of homework and a lot of study, and that I had to have a lot of ideas when I came to the rehearsal. But after working for a number of years, I found that often I would lose time because I had done so much preparation, and I would be trying to mold a situation into an idea that was preconceived. I prefer, really, to walk into the rehearsal room with sort of just a general idea — maybe a direction in which I think a piece might go — but to look at the people, to look at the theater, the space, and to make the work with them so that it really comes and evolves from the people that I’m working with, not from me in a room alone, dreaming and thinking what it could be.

BD: Most of the works that you have done lately have been somewhat esoteric repertoire rather than the run-of-the-mill works. Is it perhaps easier to work with something where the singers have less experience — no previous productions — so that everything is new, rather than another Tosca or Bohème?

RW: No. I’ve worked, actually, in many situations. I just directed Shakespeare’s King Lear. In the company I had an actor eighty years old who performed for sixty-five years.

BD: But not always Lear...

RW: But always major roles, a big star. In this case the actor was doing something completely different for the first time in her life. I don’t know; I think each situation is unique. Sometimes it’s a play I’ve written and it’s easier to work, and sometimes it’s a play that I haven’t written and it’s easy to work, and sometimes when I’ve written one it’s difficult to figure it out. Each situation is different.

BD: When you have written a play, would you rather direct it yourself, or would you rather turn it over to someone who can see it from the outside?

RW: Up until this date, all the pieces that I have written I have directed and designed myself, with one or two exceptions. I think it’s interesting to see someone else direct and design a work that I’ve conceived.

BD: Has this been done later with other performances of the work, or other productions of the work?

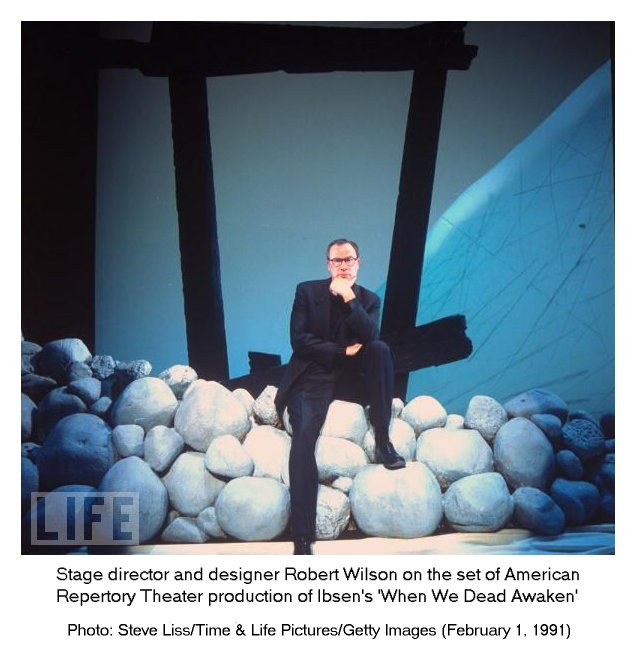

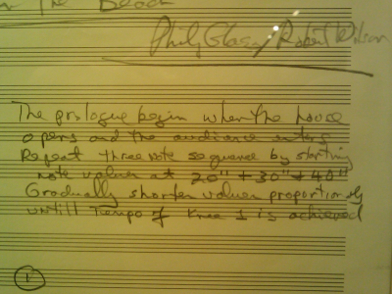

RW: It was Einstein on the Beach. [Photo at right of first page of the manuscript] It was recently redirected, redesigned, by Achim Freyer in Stuttgart. Several of my plays have been redone. There was recently a Canadian production of a play I did called The Golden Windows; there was a production last year of I Was Sitting On My Patio This Guy Appeared I Thought I Was Hallucinating. It was a very short play, an hour and a half long, directed by a young director in Belgium. But for the most part, my work and things I have done thus far probably won’t be directed by other people. It’s been created by me and performed at one time, and probably won’t be performed so much in the future.

RW: It was Einstein on the Beach. [Photo at right of first page of the manuscript] It was recently redirected, redesigned, by Achim Freyer in Stuttgart. Several of my plays have been redone. There was recently a Canadian production of a play I did called The Golden Windows; there was a production last year of I Was Sitting On My Patio This Guy Appeared I Thought I Was Hallucinating. It was a very short play, an hour and a half long, directed by a young director in Belgium. But for the most part, my work and things I have done thus far probably won’t be directed by other people. It’s been created by me and performed at one time, and probably won’t be performed so much in the future.BD: [Wistfully] Ah, but that’s what they said of Alceste and all of these other great works! They were performed, and Gluck would be perhaps even horrified that it’s being done two hundred years later!

RW: [Laughs] That’s true! Who knows?

BD: Are you going to be horrified if something that you have written is done in two hundred years?

RW: No, I’d be very pleased!

BD: Will the audiences in two hundred years understand your work?

RW: I don’t know; I would hope so. I think that my work is quite accessible. I’ve been privileged to work all over the world — in the Far East, in the Middle East, throughout Europe, South America. I’ve actually worked a lot more outside the United States than I have in the United States, and I think one reason that I’ve had this opportunity to work internationally is that the work is somehow accessible to a large public. For me, one of the basic things of theater is that it should be accessible to anyone; the man on the street or the man from Mars should be able to walk into the theater and appreciate something. Susan Sontag said in her essay Against Interpretation that “the mystery is in the surface.” And I think that’s true, that somehow the surface of a work must be mysterious and accessible. Whether one’s doing Shakespeare or Gluck’s Alceste, there must be something very simple about it. One must be able to tell one’s self, if one is an actor or a director or author, the work is about this, something, very simple. Then it can be about many things.

* * * * *

BD: Because you are often a creator on your own behalf, do you then interpret other people’s creations differently than someone who doesn’t have any hand in writing works of their own?

RW: Perhaps. My background was primarily in the visual arts, in architecture and painting, so whatever I do, I usually bring a very strong visual book to the work in terms of light, in terms of gesture, sometimes scenery, props, furniture, sculpture. I always think that what we see is what we see and what we hear is what we hear, and what we see should be as important as what we hear. So often in the theater, what we see is secondary to what we hear, and we think that the most important thing in the theater is the text, is the book, is the word. In an opera, it’s the music, but the two primary ways in which we communicate with one another is through our eyes and through our ears. So I try to make the visual book not necessarily a decoration, or there to simply support the audio book, but it can parallel, it can be as important. It is an equal partner and can reinforce what we hear, without having to illustrate or decorate.

BD: When you’re writing a play, do you believe that it can stand on its own without music, as opposed to when you perhaps collaborate with Philip Glass, that it’s something that cannot stand without the music?

BD: When you’re writing a play, do you believe that it can stand on its own without music, as opposed to when you perhaps collaborate with Philip Glass, that it’s something that cannot stand without the music?RW: The visual book can stand alone in all of my works, even with Gluck. I can take away this music and just run this as a mute work, and hopefully it would be interesting to look at.

BD: An opera as a mime show?

RW: I think I could take away the music and I’d just look at the lights and at the movements, and hopefully it could stand on its own, yeah. Architecturally it’s conceived that way.

BD: Then how does it relate to the music, which will be all-pervasive?

RW: It parallels the music. It’s a parallel event. It can reinforce the music.

BD: Is it parallel in a different car, or parallel in the same car going along the road?

RW: It varies. Sometimes it’s a parallel track, and sometimes it’s a track that crosses and meets. If one believes anything too much, it’s a lie or it’s a mistake, so it’s always important to contradict one’s self. Frequently in my work one can imagine two screens that are seen parallel. They can be out of phase or they can be in phase, in line or out of line. Maybe they’re slowly shifting so that they’re out of line, and then at some moment they suddenly line up and are parallel. Then they can shift out of focus and not be parallel. But those moments in which they do line up maybe are moments that sustain this long line, these contradictions.

BD: In a musical work, is it the music that helps dictate the pace of the in and out of phase, or is it your own work?

RW: In my work I’m not interested in collages, so that what I see may be different from what I hear, meaning that the gesture may be of a different tempi, or out of context with what is being spoken or sung. It’s not ever thought to be arbitrary; it’s something that’s structured. As I said, it’s something there to reinforce, or to help me hear and see.

BD: How much of this push-pull is going to propel the work forward, and how much it’s going to, perhaps, tear it apart?

RW: It’s all architectural to me. It’s construction and time and space, how to support this line of attention. Sometimes it can be something in contradiction and it makes more attention on the space, and sometimes it’s not. They’re aesthetic decisions that are made in a construction in time and space, so sometimes one can see, maybe, a movement on stage that’s slower or different tempi than the music. Or it’s an internal rhythm of the music; sometimes it can be quicker and sometimes it can be exactly in the tempi of the music. To me it’s boring if all the walking and all the movements are exactly in the tempi of the music, so sometimes there’s someone walking slower, someone quicker, someone with the music. It makes a denser work, a more complex work. It also relates more to the energy of the public. You find that some people are in different mental rhythms in the audience. Within a house there are very different mental vibrations of the public in the theater. And the stage is like a battery, so you can set up different energies in this battery that maybe relate to the entire audience.

BD: Does it make any difference if you’re playing in a very small house or a great big barn of a house?

RW: Sure it does. You may be doing the same gestures in a small house that you would do in a large house, but the weight or the scale of a gesture is different. It may be tracing the same line, but your projection of the energy, the way you fill the space, is different. I always say to the actors, “Go on stage, and look at the back wall. Look at the exit signs on the back wall. You’ve got to get that far! You’ve got to go to the back wall. You’ve got to fill this room with your presence. If you’re looking down at the floor, or you’re just moving your hand to your hip, the weight of that gesture must get to the person sitting on the back row of that theater.”

BD: If it’s a large theater, is that not too heavy for the people in the first five rows?

RW: No. No, no, no. One learns to project in a house and to fill a house with your just blinking an eye. That is seen on the first row and maybe felt in the back row, or seen in the back row. It’s very curious that we see so often in opera that the singer wants to make big gestures because usually we’re in big houses, and so often I find that they’re ridiculous and unnecessary. Actually, a small gesture in a big house, in big space, is larger than a big gesture!

BD: How so?

RW: Because there’s more space around it. Let’s say if I take a room that’s this size. We’re in a room that’s about twelve feet by twelve feet. If I put a car in this room, it would be quite full with this big automobile. But if I took a tiny toy car that was an inch and a half by a half an inch and I put it in this room, that little car would probably be bigger than this big car because there’s so much space around it.

BD: It’s a mental trick, then?

RW: Yes, it is. It’s a question of weight and space. This tiny little thing, with all this space around it has more weight.

* * * * *

BD: Do you try to keep your sets relatively uncluttered?

RW: Well, depends. This one I have. This one is very severe. It’s very simple. Gluck says that he thought of the music for this work and the attitude to perform it as a noble simplicity. Actually I had that in mind when I was designing and making this work. It’s very formal; it’s very classical, very architectural, like the music.

BD: Does it speak to the audience of 1990?

RW: I think it does. It’s a classical design we could have looked at three hundred years ago, and we can look at today. It’s a classical composition, which is always of interest. It’s full of time.

BD: So you haven’t tried to bring it up to date? You’ve tried to revitalize what’s there?

RW: Someone said to me earlier today, “Oh, this is very avant-garde,” but I said, “Well, maybe.” I never want to be avant-garde, although I’m frequently called avant-garde. Actually, avant-garde means rediscovering the past or rediscovering what we already know — classicism — and I think that that’s what is in this work.

RW: Someone said to me earlier today, “Oh, this is very avant-garde,” but I said, “Well, maybe.” I never want to be avant-garde, although I’m frequently called avant-garde. Actually, avant-garde means rediscovering the past or rediscovering what we already know — classicism — and I think that that’s what is in this work.BD: If you don’t want to be avant-garde, what do you want to be?

RW: I’m an artist, simply. I never wanted to create a new form or a new theater. I’ve just done what seemed right or natural to me. I’m very intuitive in my work. Martha Graham said a long time ago, “The body doesn’t lie,” and I think that’s true. Frequently I don’t know what to do. I just shut my eyes and ask myself, “Should I do this, or should I do that?” And I say, “Oh, I think I should do this,” and I usually do.

BD: It’s usually right?

RW: For me, yeah.

BD: Let me ask the big philosophical question, then. What is the purpose of theater? Or perhaps even bigger, what is the purpose of the arts?

RW: In this case, theater, it’s a forum, and it serves a unique function in society in that it brings people together. It brings people together regardless of political viewpoints, economic backgrounds, political backgrounds or social backgrounds. We come together and we share something for a brief period of time. And in this profession, theater, it’s unique in that it brings together, for me as an artist, my interest in painting and sculpture and light and poetry and music and movement and architecture. All of the arts can be brought together into this forum in which we have an exchange with the public.

BD: Do you get something back from the public, as well as giving the public something?

RW: Exactly. That’s why we make theater. We make theater for the public. The best performer is one who performs first for himself, but we always have in mind that we’re doing it for the public. We perform for ourselves, and we invite them to come and experience what we have made for them. My theater is not a theater of interpretation, so therefore it differs from most other theater that we see today, or work by other directors and authors. For me, interpretation is not the responsibility of a performer or the director or designer; interpretation is for the public. That’s why we make the work, and we invite the audience to come in to see this. When we present this work to them, we present it with a question. We say, “What is it?” And the reason we ask this question is to have the audience there, and they can say what it is. We try not to say what something is, but to ask a question, and that’s the reason to have people in the forum — to have an exchange.

BD: So you put performers on the stage to say, “What am I doing?”

RW: Yes, exactly.

BD: I assume there is no right or wrong answer?

RW: There are many answers, but we’re not in the theater to dictate to the audience. That’s fascism. I’m not interested in that. I’m not interested in telling an audience how to think. That’s what I find very disturbing about most theaters — they’re too fascistic for my taste.

BD: Are you not leading the audience at all in a certain direction?

RW: One can indicate directions, but one never insists on a direction if one’s doing a work like Alceste, or a work like King Lear, which I just finished directing in Germany. It’s impossible to fully comprehend Shakespeare; it’s too complex. If one has an interpretation of Lear, it’s a lie! Lear’s too complex; there are too many facets and meanings to it. That’s what makes it great; that’s what makes it rich. That’s why it’s been with us so many years, and it’ll be with us many years to come. It’s a mystery. I can read Lear tonight, and I can read it one way, and I can read it tomorrow, and I can read it another way. Two weeks from now I can read it still another way. There’s no one way to read through King Lear; there are many ways, and to have an interpretation of Lear narrows the possibilities of all these caustic meanings.

BD: Is this, perhaps, what makes certain works greater than others, that they have so much depth to plumb?

RW: I think so. I think that they are multi-faceted and have many sides to them. Why are we still fascinated by Medea? Because we can identify with that woman. We don’t really understand her, but we can see ourselves in her. It’s a very complex subject matter. She’s a very contemporary woman. We read about her every day in the newspaper; we hear about her on the radio. She’s still with us today, very much so.

BD: So could you do a season of a couple of plays that are about Medea and the various operas that are about Medea — all these different ways of looking at Medea?

RW: I think so. I’ve done three or four productions of Medea myself. I’ve done a Marc-Antoine Charpentier baroque opera of Médée. I did a Euripedes Medea. I also wrote an opera based on Euripedes’ Medea. I did Heiner Müller, the East German playwright’s, Medea. And I did them all at once, actually presented them together in the opera house in Lyon, and then they all moved to Paris where they were shown in various theaters. At one time they were all in one theater in Paris, the Champs-Élysées.

BD: And you still didn’t get to the bottom of it?

RW: No, I’m still fascinated. I met Montserrat Caballé last January in Amsterdam. She said, “Oh, I want to do Cherubini’s Medea with you!”

BD: So then did you try to pencil that into your calendar?

RW: Yeah, I’m thinking about it. I’d love to work with her. She’s such a great lady! Such a beautiful voice. The light, the color in the voice is so special.

* * * * *

BD: Let me ask about your calendar. You get offers for all kinds of things and you have all kinds of ideas in your head. How do you decide what you are going to spend your limited amount of time on?

RW: I plan very far in advance. I plan that in the next four or five years I’m doing three or four creations, and that takes time. At the same time, I had planned some years ago that I would do more traditional works in opera. I’m directing Tristan and Isolde at the Bastille in Paris. I’m doing the Magic Flute of Mozart there next year. I’m doing Don Giovanni and Lohengrin, and I’m doing Parsifal in Hamburg. I’m doing three Wagners and three Mozarts, but I’m also writing three new operas, too.

RW: I plan very far in advance. I plan that in the next four or five years I’m doing three or four creations, and that takes time. At the same time, I had planned some years ago that I would do more traditional works in opera. I’m directing Tristan and Isolde at the Bastille in Paris. I’m doing the Magic Flute of Mozart there next year. I’m doing Don Giovanni and Lohengrin, and I’m doing Parsifal in Hamburg. I’m doing three Wagners and three Mozarts, but I’m also writing three new operas, too.BD: You’re writing the text for these operas?

RW: And the visual book.

BD: And then you give that to the composer?

RW: Yes, I work with a composer on the timing and the structuring of the themes and the ideas.

BD: Are you ever surprised with what kind of music comes out of the composer’s mind when he sees your directions?

RW: Sometimes, yeah. I’ve worked with many different composers. I just created a work with Tom Waits in Hamburg that’s going to Paris this fall and is going to make a world tour. The year before that I created a new opera at La Scala with Giacomo Manzoni, an Italian composer. The same year I created a work with Dutch composer Louis Andriessen. I was just on the phone last night with a thirty year old composer from Leningrad, and we’re going to do a work at the end of next year together.

BD: Will it be in English or in Russian?

RW: It’s going to be in Russian.

BD: One last question — where is opera going today?

RW: I think opera is gaining a public. In ’76, when I did Einstein on the Beach with Philip Glass, at that time we thought of opera as really being something that’s part of the nineteenth century. Young people didn’t really go to the opera so much. But now I see in Europe, I see in America, more and more people of my generation or the generation below me writing operas, and a young public going to see these operas. I think that we’re getting a larger public. I think that the works are becoming more visual, and that way perhaps more accessible. More of the visual artists are participating; painters and sculptors are involved in the making of operas, in the creation of operas. I think it’s becoming more like a renaissance art form.

BD: Are we working on this form, or are we reinventing the form?

RW: I think we are rediscovering, yeah.

BD: I hope you’re part of it for a long time!

RW: Thank you. I hope so, too.

Robert Wilson (director)

Robert Wilson (born 4 October 1941) is an internationally acclaimed American avant-garde stage director and playwright who has been called "this country's — or even the world's — foremost vanguard 'theater artist'" . Over the course of his wide-ranging career, he has also worked as a choreographer, performer, painter, sculptor, video artist, and sound and lighting designer. He is best known for his collaborations with Philip Glass on Einstein on the Beach, and with numerous other artists, including William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Tom Waits, and David Byrne. Wilson was born in Waco, Texas, and studied Business Administration at the University of Texas from 1959 to 1962. He moved to Brooklyn in 1963, receiving a BFA in architecture from the Pratt Institute in 1965. He also attended lectures by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (widow of László Moholy-Nagy), studied painting with George McNeil, and studied architecture with Paolo Soleri in Arizona. In 1968, Wilson founded an experimental performance company, the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds (named for a dancer who helped him overcome a speech impediment while a teenager). With this company, he created his first major works, beginning with 1969's The King of Spainand The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud. He began to work in opera in the early 1970s, creating Einstein on the Beach with Philip Glass, which brought the two artists world-wide fame. In 1983-1984, Wilson planned a performance for the 1984 Summer Olympics, the CIVIL warS: A Tree Is Best Measured When It Is Down; the complete work was to have been 12 hours long, in 6 parts. The production was only partially completed — the full event was cancelled by the Olympic Arts Festival, due to insufficient funds. In 1986, the Pulitzer Prize jury unanimously selected the CIVIL warS for the drama prize, but the supervisory board rejected the choice and gave no drama award that year. Wilson is known for pushing the boundaries of theatre. His works are noted for their austere style, very slow movement, and often extreme scale in space or in time. The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin was a 12-hour performance, while KA MOUNTain and GUARDenia Terrace was staged on a mountaintop in Iran and lasted seven days. In addition to his work for the stage, Wilson creates sculpture, drawings, and furniture designs. He won the Golden Lion at the 1993 Venice Biennale for a sculptural installation. Louis Aragon praised Wilson as: "What we, from whom Surrealism was born, dreamed would come after us and go beyond us". |

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded backstage at the Opera House in Chicago on September 6, 1990. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB a few days later to promote the performances. A transcription was made and published in The Opera Journal in December, 1991. It was re-edited and posted on this website in 2009.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu