Into the Wild: Faviken Restaurant in Northern Sweden by

The text below is a phonetic transcript of a radio story broadcast by PRI’s THE WORLD. It has been created on deadline by a contractor for PRI. The transcript is included here to facilitate internet searches for audio content. Please report any transcribing errors to theworld@pri.org. This transcript may not be in its final form, and it may be updated. Please be aware that the authoritative record of material distributed by PRI’s THE WORLD is the program audio.

Schachter: We need marrow and heart with grated turnip and turnip leaves that have never seen the light of day – very important – grilled bread, and something called lovage salt. We need a very fresh cow’s heart to start with and then a very fresh cow’s femur.

[clip ends]

The text below is a phonetic transcript of a radio story broadcast by PRI’s THE WORLD. It has been created on deadline by a contractor for PRI. The transcript is included here to facilitate internet searches for audio content. Please report any transcribing errors to theworld@pri.org. This transcript may not be in its final form, and it may be updated. Please be aware that the authoritative record of material distributed by PRI’s THE WORLD is the program audio.

Schachter: We need marrow and heart with grated turnip and turnip leaves that have never seen the light of day – very important – grilled bread, and something called lovage salt. We need a very fresh cow’s heart to start with and then a very fresh cow’s femur.

[clip ends]

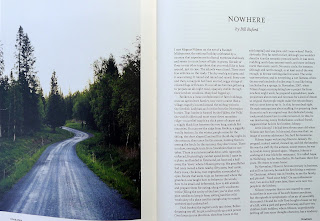

Six hundred miles north of Stockholm, on a remote hunting estate near Jarpen, Magnus Nilsson mans the kitchens at a restaurant straight out of ancient agrarian times.

"We do things as they have always been done at Jämtland mountain farms," he says. "We follow seasonal variations and our existing traditions." Everything on the 12-course tasting menu at Faviken is made with just-foraged ingredients: local garden produce, locally raised meat, wild game, herbs, and mushrooms from the estate, cheese and other dairy from the surrounding region of Jämtland, and seafood from the neighboring region of Trøndelag, Norway. During the summer, the chefs build up their stores for the dark winter months: "We dry, salt, jelly, pickle, and bottle."

N.B. If you're not planning a trip to the northern edges of Sweden anytime soon, Phaidon has just published Faviken, a cookbook by Nilsson. All photos via Faviken unless otherwise noted.

Above: Swedish chef Magnus Nilsson in his trademark furs. Photo by Howard Sooley via Nowness.

Above: The dining room accommodates just 12 diners.

Above: Local scallops.

Above: Dried herbs function as decor.

Above: A single log serves as a side table. . Photo by Howard Sooley via Nowness.

Above: Scenes from the dining room; hanging cured meats add a medieval touch.

Above: Illumination by fire: candles and a wood-burning stove.

Above: Nilsson's furs, at the ready. . Photo by Howard Sooley via Nowness.

Above: A view of the snowy landscape.

Executive Chef Magnus Nilsson is a rising culinary star with a message: by choosing to cook both locally and sustainably, Nilsson communicates a deep appreciation for “real food” (rektún mat in his local dialect) that has contributed to his success. He hunts, fishes and forages, and is well-versed in making the most of his sub-Arctic environment. The 30-year old Swedish chef has been running Fäviken Magasinet since 2008, and the restaurant’s rural location in Järpen, 750 km north of Stockholm, is integral to both Nilsson’s food and philosophy.

Nilsson is dedicated to making the most of the produce at hand, rather than adhering to constraints. He imports sugar, salt and rapeseed oil from southern Sweden and everything else is sourced, grown or otherwise produced in the surrounding area. Fäviken is a small restaurant – serving between 12 and 16 guests each night, depending on the size of the tables – and employing 11 staff members, including Nilsson. With the increased coverage of Nordic restaurants in past years, Fäviken quickly became an international dining destination (with accommodation), and was recognized as one of the World’s 50 Best Restaurants 2012.

Capercaillie and coniferous forest from Fäviken (Photos: Phaidon Press, 2012)

The decision to use locally sourced produce was practical, rather than ideological. “It just kind of made sense,” says Nilsson in an interview prior to his appearance at Toronto’s Terroir Symposium. “One of the few ways of actually making a difference when it comes to produce is to communicate with the person who produces it.” Quality is of utmost importance to Nilsson, and he considers the reduced ecological footprint of using locally sourced food to be a very positive side effect of what they do, “but it’s still a side effect of the quest for quality.”

He was raised in the small city of Östersund in Jämtland, which is near Fäviken, and knows the local flora and fauna well. “[The knowledge has] been there all the time but I use it differently now than I did in the beginning,” Nilsson says. He grew up hunting and fishing, and today foraging plays a major part in the work he does at the restaurant. Wild vegetables such as fiddlehead ferns, wild herbs and seasonings such as juniper, and other wild foods such as mushrooms, berries, moss and lichens, all feature prominently in his dishes.

The vegetable garden at Fäviken

Nilsson started a vegetable garden when he took over Fäviken, and it has increased in size over the years – from 20 square metres in 2008 to 6,000 square metres today. Given the short growing season in Järpen, preservation techniques are critical in order for Nilsson to utilize the produce throughout the year. Nilsson and his team employ a number of different techniques – including storage clamps (used to temporarily store root vegetables), drying, pasteurizing, pickling and fermentation – depending on the results they would like to achieve.

Given that Fäviken is known for signature dishes such as “Diced raw cow’s heart with moose marrow on a bed of shredded swede,” one might incorrectly assume that the ethos is primarily meat-focused. “Vegetables and plants are really what define most cuisines,” Nilsson says. ”If you have a piece of protein, like a piece of chicken and you have a carrot prepared in a particular way, and you have some condiments of let’s say sage, and then you exchange the chicken for lamb or veal, you will have pretty much the same dish.” He explains that the dishes would pair with the same wine, and be perceived similarly as well. “If you exchange the carrot for a beetroot, then you have a new dish even though you might have kept the same chicken,” he adds with a laugh.

Grated red beets

Nilsson’s presentation at the seventh annual Terroir Symposium went a step further, and addressed the ethics of meat-eating. He highlighted several problems associated with meat-eating – including increased consumption and production, and the resulting strain on the environment, as well as today’s distance from food production. “Vegetables washed, cleaned from every little scrap of dirt, lying in a plastic tray. A slab of pink meat that has been most likely produced and washed in a large production unit with a minimum of human interaction just to produce basically a slice of cheap protein. That’s what food is for most people,” he says. “I want to remind everyone what meat really is.”

As one of Nilsson’s presentation slides reads, “Meat is the remains of what was a living individual that we selfishly raised and killed with the sole purpose of feeding ourselves.” As someone who grew up hunting and fishing, the chef witnessed the births and deaths of animals firsthand. As Nilsson states during his presentation, despite this fact, he himself didn’t give meat-eating much thought until what he describes as, “one of the few defining moments I’ve had in my life so far – something that really made me think.”

Magnus Nilsson butchering, left, and discussion meats in the Fäviken dining room

A few years ago, Nilsson and his family moved to a small farm and bought a flock of sheep both to prevent the forest from encroaching on the surrounding meadows, and to have lambs to eat in the autumn. He described he had been present for the slaughter of many lambs in the past, and had killed many himself. The main difference being that he hadn’t had a relationship with any of the animals as they were from larger flocks, while his flock consisted of nine ewes and approximately 13 lambs. His children had named the lambs and the family had gotten to know them over the summer.

Nilsson even had his favourite – “a very handsome young ram” – who as one of the largest, had been marked for slaughter. He describes the day of the slaughter in detail – the weather was cool, and as he walked up the hill to the flock, some of the more adventurous lambs, including his favourite, walked to meet him. “Without thinking much more I scooped my right leg over [my favourite] and held his body between my knees. I petted him one last time on the back of his ear, and I pushed the bolt gun against his head and I pulled the trigger,” Nilsson says. “And his body just twitched a bit and fell to the ground, and I cut the arteries in the throat. You have to do that to actually kill the animal. The shot in the head is just anesthetizing.”

Fäviken Magasinet in Järpen, Sweden

When Nilsson got back to the house, he realized that he had been crying, which he adds, “is something that I do from time to time but not that often and usually not when handling food.” He cites this as an influential experience as it caused him to make some realizations. “You get to know the individual and you see it grow and then kill it for eating it,” Nilsson says. “And I thought that if everyone had to do this in the whole world, everyone had to watch an animal be born, then watch it grow, name it, get to know its character, then kill it themselves and eat it, none of these problems would exist anymore because no one would treat meat so carelessly,” he adds to great applause.

Nilsson reiterates his point by sharing a clip of the 1949 French short documentary film written and directed by Georges Franju, Le sang des bêtes (Blood of the Beasts), which contrasts depictions of a slaughterhouse with images of Parisian suburban life. “This is the reality of meat production. We raise individuals, we kill them, and we eat them,” he says following the clip. He emphasizes that he doesn’t believe in constraints on food choices, but rather that people start making more active, informed choices. “That’s going to shape the way to a more sustainable way of consuming, and that’s the shape that we really need in the future.”

Magnus Nilsson has been named one of the top 10 chefs in the world. His restaurant Faviken in rural Sweden made the list of The World’s 50 Best Restaurants in 2011.

He has a new cookbook called, simply, “Faviken.” The meals are unconventional. As he writes, “the recipes in this book are not like those in many other cookbooks.”

As long as we’re talking about lists, that may top the list of Understatements of The Year. The book includes recipes for “black grouse in hay” and “marrow and heart with grated turnip and turnip leaves that have never seen the light of day, grilled bread and lovage salt.”

And contrary to most cookbooks, there are no measurements. Nilsson urges cooks to “read the recipes with an open mind” and follow the principles. He says you’ll never make the dish like he does, and that’s okay.

The World’s Aaron Schachter visits a local Whole Foods in search of ingredients to make a meal from Faviken. It’s not easy to do.

Read the Transcript

Aaron Schachter: Now, OK. Here’s how it works when we do celebrity chef interviews at The World. The publisher sends a cookbook to our newsroom and one of us takes the book home and attempts to make at least one of the recipes. Makes sense, right? That’s what I wanted to do before speaking with Swedish chef Magnus Nilsson. He shot straight into foodie stardom after his restaurant in rural Sweden – and we mean rural – Faviken, was proclaimed the most daring in the world by Bon Appetit magazine. Now, he has a new cookbook out also “Faviken” and I wanted to see what I could make from it. First step: a trip to a local Whole Foods to find the ingredients. Marketing team leader David Remillard tried to help me out, but it wasn’t easy.

[Clip plays]

David Remillard: The marrow or the femur we definitely can order for you. We can talk to our meat guy, our butcher, about the heart because I think we can also get that in for you. And what was the other things that you also needed?

Schachter: We need one turnip, that’s easy enough.

Remillard: But that hasn’t seen the light of day?

Schachter: “That is stored in the cellar with its little yellow leaves that have started sprouting towards the end of winter.”

Remillard: I have turnips, I have local turnips. I can’t promise you though that they haven’t seen the light of day.

Schachter: Shall we try and find our cow’s heart and femur?

Remillard: Let’s go. I’ll take you over to the butcher.

Robert Mitchell: Hey, how you doing? Mitch.

Schachter: Aaron. Nice to meet you.

Mitchell: Nice to meet you too.

Schachter: So we’ve come to you to find ingredients, are you ready for this?

Mitchell: Yeah.

Schachter: Marrow and heart.

Mitchell: Femur bones? We have ‘em. We can get ‘em in anytime you ask and we’ll look to see if we can get some beef hearts in. I’ll let you know if I can do that.

Schachter: What was the other one we had a little trouble with? Oh, you know, we needed a retired dairy cow.

Mitchell: A retired dairy cow? Let me see what I have in the back here. Give me one second.

Remillard: No retired dairy cows?

Mitchell: No, no retired dairy cows here. We’ll massage ‘em too while they’re growing.

Schachter: You know what would be great is if give ‘em this jazz music for a massage.

Mitchell: Oh, yeah, definitely. Headphones.

Schachter: Headphones. And then he’s retired and we can eat him.

Schachter: That was a butcher at Whole Foods, Robert Mitchell, helping me out with my shopping list. I am joined now by Swedish chef, Magnus Nilsson, one of the top ten chefs in Europe. Magnus, thank you for joining us.

Magnus Nilsson: Thanks for having me.

Schachter: Now, we poked a little fun there with that tape.

Nilsson: It was great.

Schachter: But, as you could tell, it was a little hard to get any ingredients for your . . .

Nilsson: I think you did pretty well actually.

Schachter: Really?

Nilsson: Yeah, at least you found the femur.

Schachter: Yeah, that’s true.

Nilsson: Yeah.

Schachter: I had to order it though. It takes about ten days. But a lot of your food takes time to cook doesn’t it?

Nilsson: Yeah, it does. And a lot of the food needs to be planned ahead a long time in the restaurant as well.

Schachter: A year, one of the recipes, right?

Nilsson: One of them is probably a year, yeah.

Schachter: I have to tell you, I was fully prepared to just make a complete joke out of this book, but the fact is, whether or not you can cook these meals, the book is absolutely stunning.

Nilsson: That’s very nice of you. Thank you.

Schachter: But who is the book for then? I mean some of the other celebrity chefs, Jamie Oliver comes to mind, make food that they hope people will go out and make. They will get the book on Tuesday and make the dinners on Wednesday. That’s not going to happen with your book.

Nilsson: No, and that’s probably not the idea. From my part, the idea is that to write and produce this book and have people read it. It’s all about sort of explaining the context of my restaurant.

Schachter: Your restaurant, Faviken?

Nilsson: Yeah, exactly. For people who haven’t got the same cultural background as I have, to kind of explain why it makes sense what we do up there.

Schachter: Yeah, I’m looking through the book now and, as I said, it’s very beautiful, very interesting, but a bit hard to understand, this kind of food. Tell me about what it is you do up there.

Nilsson: So I think that like actually if you look at every chef everywhere, the most important that everyone makes in a kitchen is to try to make the most out of whatever possibilities and difficulties you have in your situation, in your surrounding.

Schachter: Local food you mean?

Nilsson: No, not necessarily, but you have to make the most out of whatever you have. Now, for us, that’s local food. We live in the countryside in the northern parts of Sweden and that’s something that works for us, it makes sense, but if you’re in a city, it might be something else, so . . .

Schachter: The restaurant seats about twelve people. It’s very hard to get to. There’s a great story at the beginning of the cookbook from a travel writer about him getting there. It sounds like quite the trek. Is this sort of one of those restaurants out of James Bond or something where diners pay a thousand dollars each, all twelve of them, and get this fantastic meal?

Nilsson: They don’t pay quite a thousand dollars each, but it’s definitely a costly restaurant, and it has to be because it costs a lot of money to get those products in and to be able to prepare them the way we do.

Schachter: Now, Magnus, yesterday, we asked listeners to send in questions to ask you and I’d like to read you a few if you don’t mind.

Nilsson: Yeah, sure. Go ahead.

Schachter: OK. What time of year is best to visit Faviken?

Nilsson: Well, it depends kind of on what you like. Summer is probably the time of the year when we’re most like most other restaurants and there’s a lot of fresh vegetables, for example, there’s a lot of thing straight from the garden. Autumn, there’s a lot of game birds, mushrooms, things like that. Winter is quite particular because everything we serve in terms of vegetables then has been stored or prepared in some way to keep. And then in Spring there’s a lot of foraged food, so it depends on what you like.

Schachter: That is celebrity chef, Magnus Nilsson, voted by some one of the top ten chefs in Europe. His restaurant, Faviken, one of the fifty best restaurants in the world according to the Wall Street Journal I believe it was. Congratulations. Thank you for joining us.

Nilsson: Thank you for having me.

Schachter: And in about ten days now my cow’s femur might be ready and maybe I can try a recipe from your book.

Nilsson: Give me a call and tell me how the cow’s femur turned out.

Schachter: OK. I will do.

Nilsson: Good.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu