Via Flickr:

Da un articolo della giornalista Monica Peruzzi.

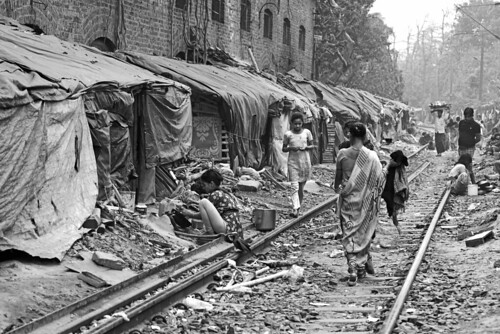

Lo slum di Calcutta che sorge lungo la ferrovia. In lontananza si sente il fischio del treno. La gente si alza, lenta, e ordinatamente, smette di fare quello in cui era impegnata e si sposta verso i lati della ferrovia. Il popolo dei binari è abituato al passaggio dei treni, ne riconosce i segnali, ne può quasi sentire l'odore. Capre, galline, cani e gatti, seguono i padroni. I bambini scappano e si rincorrono, scalzi e sudici. Sono bambini, come quelli che abitano ogni altra latitudine del Mondo. Sono bambini, e per loro il passaggio del treno è un gioco. Sembra di guardare il mare: l'arrivo della marea, che onda dopo onda, porta via metri di spiaggia. È una sinfonia di suoni e voci che stordisce. Il treno corre così vicino alle baracche, che pare impossibile vederle ancora lì, miracolosamente in piedi, dopo il suo passaggio. Poi tutto torna come prima, con la stessa lentezza, lo stesso ordine, lo stesso concerto di voci e rumori. C'è chi accende il fuoco per riscaldarsi e cucinare, chi si lava con l'acqua raccolta alle fontane, in città, chi gioca a carte, chi si pettina, chi salta la corda, chi sta semplicemente seduto, a guardare l'orizzonte, in attesa del prossimo treno. Alla stazione di Calcutta ne arriva uno ogni 15-20 minuti e il capotreno sa che deve suonare forte. Deve suonare forte perché c'è sempre quello che si è stordito di alcol per non sentire la fame e il dolore, c'è sempre un bambino che non capisce il pericolo e si attarda sulle rotaie. Il popolo dei binari è il popolo di uno degli slum più grandi e poveri di Calcutta, il capoluogo del West Bengala. Le baracche, che stanno a mezzo metro di distanza dalle rotaie, sono fatte di stracci, vecchi pezzi di plastica rotti, cartoni, lamiere, tubi di alluminio, assi e pali di legno. Solo in qualche baracca c'è l'elettricità, perché il proprietario è riuscito ad attaccarsi ai cavi della municipalità, in un pesante groviglio di fili che penzola pericolosamente da tutte le parti. Sono arrivata a Calcutta per parlare degli abusi sessuali sulle donne, sugli esseri più indifesi, emarginati, che per religione non hanno alcun diritto, tantomeno quello alla felicità. Sono arrivata a Calcutta con l'idea di raccogliere le storie di chi aveva subito quel tipo di violenza, perché questo è lo Stato dell'India in cui si è registrato il maggior numero di abusi sulle donne, quest'anno, secondo i dati del registro dell'ufficio nazionale sul crimine. Eppure è stato solo qui, lungo questi binari, che ho capito. Ho capito che per raccontare quello che sta davvero accadendo nel Paese, bisogna prima respirare l'odore della violenza quotidiana, quella della negazione stessa dell'essere umano. Una violenza che non può essere compresa senza toccare quelle mani che si tendono davanti a te per salutarti, senza fermarsi accanto a quell'umanità che guarda l'orizzonte, in attesa del prossimo treno.

From an article of journalist Monica Peruzzi.

The slum in Calcutta, which lies along the railway. In the distance you hear the train whistle. People rises, slow, and neatly, stop doing what he was engaged and moves towards the sides of the railway. The track people accustomed to passing trains, it recognizes the signals, you can almost smell. Goats, chickens, cats and dogs, followed by the masters. Children run away and chasing, barefoot and filthy. Are children, such as those that inhabit each other latitude in the world. Are children, and for them the passage of the train is a game. It seems to look at the sea: the arrival of the tide, wave after wave, brings forth yards of beach. Is a Symphony of sounds and voices that stuns. The train runs so close to the barracks, which seems unable to see them still there, miraculously standing, after its passage. Then everything returns as before, with the same slow, the same order, the same concert of voices and noises. There are those who lit the fire to keep warm and Cook, who washes with water fountains, library in town, who play cards, who Combs, who jump the rope, who's just sat, looking at the horizon, waiting for the next train. The Calcutta station goes every 15-20 minutes and the conductor knows should play strong. Must play strong because there is always what has stunned alcohol not to feel hunger and pain, there is always a kid who doesn't understand the danger and lingers on the Rails. The people of the tracks is the people of one of the largest and poorest slums of Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal State. The huts, which are half a meter away from the rails are made of rags, old bits of broken plastic, cardboard boxes, plates, aluminum tubes, boards and wooden poles. Only in some Shack there is electricity, because the owner failed to latch on to the wires of the municipality, in a tangle of wires hanging dangerously from all sides. I arrived in Calcutta to talk about sexual abuse on women, on persons most vulnerable, marginalized, and religion have no right, nor that happiness. I arrived in Calcutta with the idea of collecting the stories of those who had undergone that kind of violence, because this is the State of India which recorded the highest number of abuses on women this year, according to data from the national registry office on crime. Yet it was only here along these binaries, which I understand. I understand that to tell what is really happening in the country, we must first breathe in the smell of daily violence, the antithesis of the human being. A violence that cannot be understood without touching those hands that you tend to say good-bye before you, without stopping next to that site that looks at the horizon, waiting for the next train.

Traducere // Translate

Kolkata Slum

Abonați-vă la:

Postare comentarii (Atom)

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu