Last June, Men’s Fashion Week in Milan took place a few days after Miuccia Prada and her husband, Patrizio Bertelli, who runs the business end of their empire, had raised $2.1 billion with a long-delayed, much ballyhooed initial public offering on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Both the I.P.O. and Prada’s runway show—a collection of Day-Glo floral prints and nerdy plaids—inspired complaints from Giorgio Armani. “Fashion today is in the hands of the banks and of the stock market and not of its owners,” he told the press. He went on to scold Prada for “bad taste that becomes chic.” Her clothes, he added, are “sometimes ugly.”

Armani’s perception was hardly novel, and Prada might not have disagreed—“I fight against my good taste,” she has said—though she also might have pointed out that when bankers want a fashion insurance policy they buy one of Armani’s suits. He is the champion of the risk-averse, and Prada has always slyly perverted the canons of impeccability that his brand embodies. Only in the dressing room do you discover that her ostensibly proper little pleated skirts, ladylike silk blouses, and lace dinner suits are a test of your cool. If you can’t wear them tongue-in-cheek, as Prada herself does—thumbing her crooked nose at received ideas about beauty and sex appeal—they can make you look like a governess.

Invincible female self-possession is a central theme of the joint retrospective that opens in May at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Elsa Schiaparelli and Miuccia Prada: Impossible Conversations.” Its subjects were born six decades apart (Schiaparelli in Rome, in 1890; Prada in Milan, in 1949), and they never met, though some of their affinities seem almost genetic. They both had strict Catholic girlhoods in upper-crust families, with traditional expectations for women, and they both took heart from maternal aunts whose feistiness defied the mold. Schiaparelli is the more patrician—her mother descended from the dukes of Tuscany—but her father was a university professor, and so was Prada’s. Neither woman set out in life to design clothes, or even learned to sew. They were both ardent rebels and feminists who came of age at moments of ferment in art and politics that ratified their disdain for conformity. Schiaparelli was involved with the Dada movement at its inception in Greenwich Village, after the First World War; Prada was a left-wing graduate student in Milan during the radical upheavals of the nineteen-seventies.

These heady adventures delayed their careers. Schiaparelli was thirty-seven and Prada was thirty-nine when they delivered their first collections. But experience of the real world, which was a man’s world for both of them, made them intolerant of female passivity and desperation. They don’t really care what makes a woman desirable to men. Their work asks you to consider what makes a woman desirable to herself.

Andrew Bolton and Harold Koda, the curators of the Costume Institute, originally conceived of the retrospective as “an imaginary conversation,” Bolton told me. But, as they began to compile quotations from Schiaparelli and to interview Prada, they realized that this conceit was too tame. It is doubtful that the notoriously touchy Schiaparelli would have been happy about sharing a double bill, even with such an illustrious compatriot, or that Prada would have submitted to comparison with a contemporary. She is widely considered the most influential designer in the world today partly because her enigmatic code is so hard to copy: she changes the password every season.

The title of the show alludes to a famous column in the Vanity Fair of the nineteen-thirties—“Impossible Interviews”—which was illustrated by the Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias. Among the mismatched sparring partners whom he caricatured with impious glee (the fan dancer Sally Rand and Martha Graham; Adolf Hitler and Huey Long; Sigmund Freud and Jean Harlow) were Joseph Stalin and Schiaparelli:

Stalin: Can’t you leave our women alone?

Schiaparelli: They don’t want to be left alone . . .

Stalin: You underestimate the serious goals of Soviet women.

Schiaparelli: You underestimate their natural vanity.

Her “interview” with the dictator appeared in 1936, when she was at the height of her glory, and had recently returned to Paris from a French trade fair in Moscow, where her presence made news. No other couturier had been willing to risk the censure that Schiaparelli received—and shrugged off—for consorting with the Bolsheviks, and, while she was there, she presented a capsule collection of Soviet-friendly fashions suitable for mass production. One of the ensembles was a simple black dress with a high neck, worn under a red coat, with outsize pockets, and a beret. (It wasn’t, apparently, what the commissars of chic had in mind. They rejected it as too “ordinary.”)

As a moderator for the imaginary conversation between Schiaparelli and Prada, the curators turned to another provocative Italian—the novelist and semiotician Umberto Eco. In the last chapters of “On Ugliness” (2007), his lavishly illustrated iconography of the repulsive, the obscene, and the bizarre, Eco suggests how the worship of beauty, like any established religion that turns reactionary, is vulnerable to attack by freethinking apostates. Until the twentieth century, physical monstrosity was an almost universal metaphor for sin, disease, corruption, greed, inferiority, and, in the features of a witch, the primal fear of female carnality. But when the modernist avant-garde revolted at the pieties of academic art, and the bourgeois complacency that it flattered, it embraced what Ezra Pound called “the cult of ugliness.” (It was also the cult of dissonance, as in Stravinsky’s music, and of fragmentation, as in Picasso’s Cubist portraits of his lovely muses in which he smashed their features into shards.) “There is no more beauty,” Marinetti exulted in “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism.” “No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece.”

Schiaparelli was a nineteen-year-old student of philosophy at the University of Rome when Futurism erupted, and she later heeded its call in the swagger of her broad-shouldered suits, the rawness of her furs and embroidery, and a tough attitude toward any simpering or mincing in fashion which her contemporaries described as “hard chic.” Prada took up the mantle, literally, in her abrasive collections of the nineteen-nineties, which used, among other materials, wallpaper prints, nasty fabrics, bottle caps, and broken glass. In 1999, she showed a Teflon wool hiking skirt. “Brown is a color that no one likes,” she told Bolton, “so of course I like it because it’s difficult.” She has often said that when she hates something herself—crochet, for example—she works out her antipathy in a collection: it gives her the space “to be intrigued.” (She also hates golf, apparently—a theme of her June menswear.) Last year, she designed a collection, in cheap cotton, inspired by hospital scrubs. “If I have done anything,” she told British Vogue, “it was making ugly cool.”

“Hard Chic” and “Ugly Chic” are two of the seven categories (with “Naïf Chic,” “The Classical Body,” “The Surreal Body,” and “Waist Up/Waist Down”) into which Bolton and Koda group the examples of Schiaparelli’s couture and Prada’s ready-to-wear (which is mostly from her runway shows) at the Met. The exhibits are juxtaposed with quotations from both subjects, who seem to agree that nothing is dowdier than solemnity. Prada has obviously studied Schiaparelli closely, and whether or not she has channelled her through Saint Laurent, as Bolton suggests, the kinship between many of their designs seems almost mimetic. Yet Prada’s citations of Schiaparelli—a peekaboo raincoat in transparent vinyl, empire-waist dresses with trompe-l’oeil pleats, deadpan mourning-wear, draped ombré gowns, whimsical appliqués, and the ubiquitous motif of disembodied lips—are an exercise in sampling, not imitation. They enrich and complicate, rather than merely translate, her models, and they illustrate the way that critics and artists of every generation reinvent the formal languages that they inherit.

Schiaparelli and Prada are most alike—indeed, nearly identical—in their ambition to be unique. (Prada dominates the runways and the fashion press season after season mostly by pleasing herself; the Prada style is a distillation of her personality.) But, in at least one respect, they bear no comparison. Even the Devil wears Prada, and millions know her name. Schiaparelli presented her last collection of couture in 1954, and if she is remembered at all outside the fashion world it is mostly by association with a color that she made her signature, an electric pink still known in France as le shocking, or with a once-famous perfume, also called Shocking, which was introduced in 1937. Its droll bottle—the hourglass torso of a female nude, sculpted by the Surrealist Leonor Fini, whose model was Mae West—caused a minor scandal that has also been long forgotten. (It is currently available on Amazon, a principal sponsor of the Costume Institute show.)

The capricious force of nature known as “the great Schiap,” however, was once the reigning queen of couture. In 1934, Time ran a business story on her prodigious success and put her on the cover. The flattering photograph softens her austere features, and the furtive glamour that she projects hints at erotic secrets. (But the young Elsa, as a daughter and a sister of beautiful women, “was always being told,” she wrote, “that I was ugly,” and her only marriage—an elopement, in her early twenties, with a faithless cad who abandoned her in New York—may also have been her only experiment with love.) Between 1927 and 1940, she generated a meteor shower of ideas that revolutionized the way women dress. In the column of her practical innovations are wraparound dresses, culottes, overalls, the jumpsuit, mix-and-match separates, and those Futurist power suits whose linebacker shoulders and tapered cut minimized the padding on a female body. Her radical experiments with fabrication produced paper and plastic clothes, fantasy furs, Plexiglas accessories, camouflage prints, and barklike crumpled silks. In 1935, she became the first designer to stage a fashion show as entertainment, with a set, music, and the skinny models who quickly supplanted all other native species.

Comedy had a niche in fashion before Schiaparelli, though much of it was unintentional. When she embellished a cotton summer dress with seed packets, or an evening bolero with dancing elephants, she stole the flame of irony from her comrades in the avant-garde. Cocteau, who sketched some of her embroideries, commissioned her to create his film and theatre costumes, but Salvador Dali was her prime accomplice, and their surreal couture, which strips away the veils that have always disguised fashion’s romance with fetishism, are the first true hybrids of clothing and art. Among their collaborations were a belt buckle in the form of lips; cocktail hats in the shape of a lamb chop, a high-heeled shoe, and a vagina; and a white muslin evening gown that Wallis Simpson chose for her trousseau. Dali had painted the skirt with a bright-red lobster, which matched its cummerbund, and Cecil Beaton photographed the future Duchess wearing it serenely, despite—or perhaps to mock—her reputation as a scarlet-clawed predator.

The last of Schiaparelli’s duets with Dali is also the most troubling, and it is hard not to read it as a work of protest art. The women who could afford her couture, and the men who paid their bills, had ridden out the Depression in Paris, Saint-Tropez, or New York, but, wherever they lived, it was a Shangri-La, sealed off from the blizzards of violence and misery howling around them. The masterpiece in question—a simple sheath known as “the tear dress,” from 1938—was a warning salvo from the outside world, meant, perhaps, to breach their sense of inviolability. Trompe-l’oeil incisions on the pale-blue silk (a print by Dali) represent wounds inflicted on the skin of a living creature. The cuts have been folded back to reveal bloody sinews. Appliqués on a matching mantilla reproduce the incisions. In 1940, Schiaparelli fled Paris for New York, and spent the war years volunteering for the Red Cross and raising money for pro-Allied French charities.

In 1973, the year that Schiaparelli died, Miuccia Prada (whose given name is Maria) was a twenty-four-year-old graduate student at the University of Milan. Having earned a doctorate in political science, she abruptly changed course and spent the next five years training as a mime at Milan’s Piccolo Teatro, under the legendary director Giorgio Strehler. Mime, like fashion, is a silent art, and in both cases a practitioner has to imagine how the language of a body will translate the message that she wishes to convey.

Like many of her classmates, Prada was caught up in the fervor of a radical period that was particularly volatile in her native city. At the opening night of La Scala in 1968, protesters hurled rotten eggs at patrons in evening dress, and the city was still in turmoil a few years later, when Armani’s slouchy, neutral new brand of chic opportunely made its appearance. Prada joined the Communist Party, and—or but—according to different reports, she wore Saint Laurent to distribute leaflets. (“But” seems to imply that if she sniffed the noxious weed of Marxism she didn’t inhale.)

Prada doesn’t like to discuss politics, but she has never disavowed her youthful idealism, and, in 2006, she says, “a party of the left” had asked her to run for parliament. She declined the invitation, noting that she likes her day job—and that it would also be impertinent for a billionaire to represent working-class Italians. (Her crocodile handbags can cost twice as much as a small Fiat.) As for wearing a little something from the Rive Gauche boutique on the front lines of the people’s struggle for hegemony, she prefers to recall having costumed herself in vintage dresses from a thrift shop and high heels. A French fashion curator has called her style “a collage of intuitions,” though Prada simply says, “I didn’t want to resemble anyone.” She has also shrewdly managed not to alienate potential customers on the left or the right. The bohemian impudence of her clothes is offset by their conservative opulence.

The young Prada, however, did resemble thousands of her peers in Europe who flirted with militancy or even married it, then got divorced, with no hard feelings. And joining the Communist Party in Italy or France has never meant renouncing the perks of your class—you can carry your card in a Prada wallet. Those wallets have now been around for almost a century. Prada’s family owned a luxury leather-goods business founded, in 1913, by her grandfather Mario, who had opened a little shop of lugubrious elegance in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, a glass-roofed arcade near Milan’s Duomo. The company’s beautifully hand-tooled suitcases, handbags, and steamer trunks were popular with a patrician clientele, and Mario received a warrant for his goods from the Italian royal family. When Prada was a little girl—her nickname was Miu Miu (she gave it to her secondary label)—the shop was off limits to the females of the family. It was Mario’s conviction, Prada has said, that women belong at home. But after his death, in the late nineteen-fifties, her mother, Luisa, took over the business, and in the mid-seventies the flame passed to Miuccia.

She started out by updating the stuffy merchandise with her own designs, and, in 1985, she introduced a line of lightweight backpacks, in a fine-gauge parachute nylon trimmed with leather, that pretty much transformed urban life for the kind of woman who walks everywhere, has a lot to carry but likes her hands free, and sees the point of spending hundreds of dollars on the platonic ideal of a schoolboy’s satchel. By then, Prada was living with her future husband. Bertelli, who started out in the handbag business, joined her company; as it grew (according to Forbes, in the late seventies its annual sales were about four hundred thousand dollars; in 2010, they were about 1.6 billion euros), he insisted that she start doing women’s wear. “I often think that to be a fashion designer, you must give up your brain,” Prada told a British interviewer, and for a while she refused. But her first collection débuted on a runway in 1988—a year after her wedding. Her bridal outfit was an “ugly chic” cotton day dress in army gray that she wore with a man’s camel overcoat.

Prada and Bertelli, who have two adult sons, live in the apartment where she grew up. (She has a separate apartment for her old clothes; she never throws anything out.) Her style is both deeply rooted in the sartorial conventions of bourgeois Milan—the drab palette and sober luxury of tailored clothes that are meant to convey substance and respectability—and incorrigibly irreverent about the ideals of womanhood (the virginal convent girl, the virtuous matron) that her class held dear. But her collections also evoke the men whom those wives and daughters dressed to please, placate, arouse, make proud, and sometimes deceive.

One of Prada’s formative influences, she told Andrew Bolton, was Luis Buñuel’s “Belle de Jour.” The film, with costumes by Saint Laurent, came out in 1967, when Prada was eighteen. It was a watershed moment for the well-brought-up girls of her generation, especially, perhaps, girls like Miuccia—cerebral but impetuous—who were just emerging from their cocoons of docility to discover feminism. “I have nothing against super-sexual fashion. What I am against is being a victim of it,” she has said. “To have to be sexy? That I hate. To be outrageously sexy? That I love.”

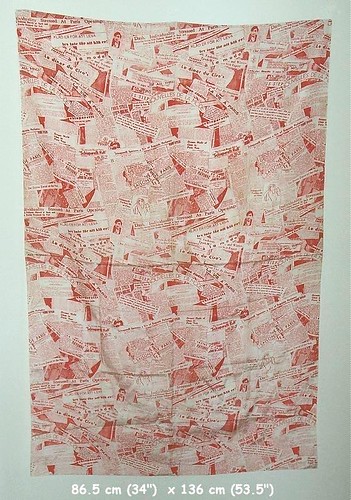

|

1930s Schiaparelli Red Silk Newsprint Fabric |

Buñuel’s heroine, Séverine, a society woman slumming in a brothel, was played by Catherine Deneuve, and Saint Laurent’s most memorable costume for her was a long-sleeved black dress with a white collar and cuffs which was nunlike in its severity. (“I’m always happiest when dressed almost like a nun,” Prada says. “It makes you feel so relaxed.”) Prada’s heroines also seem to have double lives, if not split personalities. They are often fastidious from the waist up—in a classic turtleneck or a pin-striped shirt; a Peter Pan collar; a military jacket that belies the existence of a bosom—but wanton from the waist down, in lamé or sequins (worn for day); faux-python scales; a phallic print of lipstick tubes on white silk; a peacock-feather kilt; exotic skins; see-through lace; or embroidered gauze. Skirts have always been Prada’s specialty, in part because the bottom half of a female body is all about birth and sex, she explained to Bolton. Too much attention to the “spiritual,” top half makes her “uncomfortable,” and so does being pigeonholed as an “intellectual.”

Prada’s paradoxes have often been qualified as “postmodern,” but her style—or perhaps she herself—isn’t anxious enough. Her gift for generating anxiety, on the other hand, is one of her trade secrets. For Fall 2011, she showed a series of short coat-dresses in pancake-makeup colors, belted at the waist, with panels and sleeves of mangy faux fur. The models looked as if they were swagged in roadkill. Were these outfits fabulously ugly, or inexcusably hideous?

There may be only one designer more absolute in her confidence than Prada: her fellow-honoree at the Costume Institute. Schiaparelli did more than any of her peers to promote fashion’s status as an art, and she would no doubt have found it natural to mingle at the Met with Phidias and Vermeer. Prada’s statements about art suggest that she must find her own enshrinement somewhat ironic. Her fortune has financed an adventurous private collection, an exhibition space outside Milan, and a foundation that supports cultural experiments. In 2010, she was invited to present the Turner Prize at Tate Britain, partially in recognition of her prominence as a patron. (She wore a pair of plastic banana earrings with a stark black coat.) She has also worked with the Dutch architect and urbanist Rem Koolhaas on the design of her major retail spaces, which she calls “epicenters,” in New York and Los Angeles. Yet Prada insists that her vocation and her avocation are unrelated. She has refused to collaborate on limited editions of Prada merchandise with any of the art stars in her collection. (“Anything that doesn’t sell,” she once said dryly, “is a limited edition.”) In her somewhat heretical view of a profession that often hankers after transcendence, fashion design may be a creative enterprise, concerned, as art is, with culture and identity, but it isn’t what artists do.

Prada’s useful notion of “ugly cool” may finally solve the problem of finding an English equivalent for the French epithet jolie laide. The literal translation, “pretty/ugly,” and the dictionary definition, “a good-looking ugly woman,” both fail to convey the feat of self-transformation that it represents. The nerve, the will, and the ardor of a jolie laide make you forget her homeliness. Maria Callas and Amy Winehouse both epitomize the type, and one of the most memorable jolie laides in France was Schiaparelli’s muse María Casares, the great Spanish actress who played the role of Death in Cocteau’s “Orphée.” Their charisma as performers gave a radiance to their witchy features that makes the prettiness of a perfect face seem insipid by comparison.

One of the ensembles in the category of “Ugly Chic” is a three-piece Prada suit from 1996, with a wraparound skirt, a boxy jacket, and a shapeless, high-necked shell. The fabric is a stiff synthetic, digitally printed with a smudgy grid. Each piece is a different awful color (mustard, chartreuse, mold green). It was modelled on the runway by a young Kate Moss, and even she couldn’t pull it off.

It isn’t that Prada undervalues beauty’s power—both she and Schiaparelli have dozens of ravishing ensembles in the show. But the old radical, you suspect, resents it as an unearned asset of the one per cent, and the brainy feminist wants you to understand its pathos as a love charm doomed to expire. You shouldn’t need it if you love yourself.

|

Elsa Schiaparelli, dress, printed black rayon, fall 1935, France, gift of Yeffe Kimball Slatin.

Fashion, A-Z: Highlights from the Collection of the Museum at FIT, Part One

November 29, 2011 - May 8, 2012 The Museum at FIT Fashion & Textile History Gallery www.fitnyc.edu/11600.asp

© 2010 MFIT

|

|

Prada SS2008 | Sasha Pivovarova | Steven Meisel |

The Costume Institute's Next Exhibition? "Elsa Schiaparelli and Miuccia Prada: On Fashion"

Up next after its record-breaking exhibition on Alexander McQueen, The Costume Institute will unveil Elsa Schiaparelli and Miuccia Prada: On Fashion on May 10, 2012. The exhibition, which will run through August 19, explores the striking affinities between these two Italian designers from different eras. Inspired by Miguel Covarrubias's "Impossible Interviews" for Vanity Fair in the 1930s, fictive conversations between these iconic women will suggest new readings of their most innovative work.

Left: George Hoyningen-Huené (Russian, 1900–1968). Portrait of Elsa Schiaparelli, 1932. Courtesy of Hoyningen-Huené/Vogue/Condé Nast Archive. Copyright © Condé Nast; Right: Guido Harari (Italian, born Cairo, 1952). Portrait of Miuccia Prada, 1999. Courtesy of Guido Harari/Contrasto/Redux

The title is based on Umberto Eco's books On Beauty and On Ugliness, which explore the philosophy of aesthetics. Videos in the galleries of simulated conversations between Schiaparelli and Prada will follow the book's outline and will be organized by topics such as "On Art," "On Politics," "On Women," "On Creativity," and more.

Approximately 80 designs—by Elsa Schiaparelli (1890–1973) from the late 1920s to the early 1950s, and by Miuccia Prada from the late 1980s to the present—will be displayed. Signature objects by both designers will be compared and contrasted to explore the impact of their aesthetics and sensibilities on contemporary notions of fashionability. Ms. Schiaparelli, who worked in Paris from the 1920s until her house closed in 1954, was closely associated with the Surrealist movement and created such iconic pieces as the tear dress, the shoe hat, and the insect necklace. Ms. Prada, who holds a PhD in political science, took over her family's Milan-based business in 1978 and focuses on fashion that reflects the eclectic nature of Postmodernism.

Organized by curators Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton, the show will have film director Baz Luhrmann as creative consultant, and film production designer Nathan Crowley as production designer (he was creative consultant for the Met's exhibitions Superheroes and American Woman).

The exhibition will explore how both women employed unconventional textiles, colors, and prints to play with conventional ideas of good and bad taste, and how they exploited whimsical fastenings, fanciful trompe l'oeil details, and deliberately rudimentary embroideries for strange and provocative outcomes. Experimental technologies and modes of presentation will bring together masterworks from the designers in an unexpected series of conversations on the relationship between fashion and culture.

The exhibition is made possible by Amazon.

Additional support is provided by Condé Nast.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu