Via Flickr:

World Press Photo 2008 Exhibition, Royal Festival Hall, South Bank, London SE1, UK

author: MARTIN SIXSMITH

Were an announcement made by President Obama that the White House intended to draw up a list of 100 books all Americans would be made to study and then be tested on, few would mistake it for a surefire vote winner. But during this year’s presidential campaign season, another candidate evidently thought it was. In January, during the run-up to Russia’s March 4 election, the front-runner, Vladimir Putin, proposed “a canon of 100 Russian books that every school leaver will be required to read at home . . . and then write an essay about one of them.” Reading, according to Putin, is not just an elective individual activity, but one that has decisive implications for the nation. “State policy with regard to culture must provide appropriate guidelines,” he wrote in an essay in the Nezavisimaya Gazeta newspaper, and culture shapes “public consciousness and . . . patterns of behavior.” The Kremlin’s duty, Putin explained, is to counter the decline in literacy and restore Russia as “a reading nation.”

To Western ears, this proposal may sound harmless, if a little whimsical. France’s Canute-like Académie Française rarely tires of such propositions to shore up Gallic culture against the onslaught of les Anglo-Saxons. But literature in Russia is not as neutral a commodity as it is in the West. For centuries the arts in Russia have served as a stamp of national validation, a common meeting place and a repository of shared values. In times of censorship and repression, literature has provided the nation’s sole forum for public discourse. It is a precious asset, whose ownership confers power. In the early Soviet years a poem could be a death sentence, as the poet Osip Mandelstam pointed out. “Only in Russia do they respect poetry,” he told his wife. “They even kill you for it.” He died in the gulag soon afterward. And Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn claimed that great writers have been Russia’s second government because they exercise the moral authority the politicians lack.

Hardly surprising, then, that Putin’s proposal should provoke strident cries of “hands off!” For some anti-Putin commentators the presidential book club is a sneaky bid to reassert state control of the arts. “Social engineering through state-mandated literature,” the Daily News editorialist Alexander Nazaryan called it, “nakedly Soviet in its desire to manipulate the human intellect into docility.”

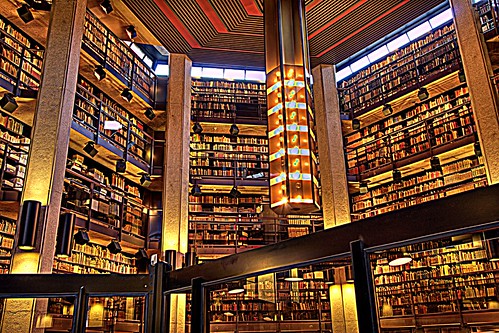

Alarmist hype? Probably. But most Russians have not forgotten the past. Under Communism the state was the nation’s only publisher. There was mass production of “approved” books, with print runs of up to a million, a blanket nyet to unofficial writers (countered by a phenomenal circulation of underground samizdat publications) and an idiosyncratic roster of foreign authors approved for public consumption (Sinclair Lewis, Robert Burns and John Galsworthy were feted and promoted; other, greater writers banned). For half a century after the Union of Soviet Writers decreed the only acceptable subject for literature to be man’s struggle for socialist progress, the public was force-fed a constipating diet of heroic pap.

In practice, state control had the effect of turning millions of readers to “serious” literature. It took only a modicum of taste to see through the worst forms of propagandist hackery, and that left the Russian classics and the poetry of the 19th and 20th centuries as the only available alternatives. As a student in Leningrad in the 1970s, I saw my fellow subway travelers reading Pushkin, Tolstoy or Akhmatova. On their evening journey they would alight at the Kirov or the Philharmonia to stand in line for ballet and classical concerts. It wasn’t that Russians were more discerning than we were; it was simply that trash fiction, Hollywood schlock and musical bubble gum were excluded from their universe by a self-interested state.

The proof that Russians are just like us came with the collapse of Communism in 1991, when a vigorous cultural free-for-all exploded in the vacuum left by the hastily departed censors. A pent-up desire for Western gewgaws, long denied by the strait-laced Kremlin, was sated with gusto. Literature, music and art turned to the trivial, the sensational and the offensive. Fiction sank to the level of Western popular culture, if not below it; pornography invaded the shelves, and cinema and TV filled up with inconsequential soaps and car-crash reality.

In recent years there has been a further modulation. The fascination with all things Western, mainly American, is abating, and serious homegrown writers have emerged. Many of them are less than enraptured with the reality of modern Russia, which naturally evokes the suspicion that Putin’s list could be a means of deflecting attention toward more patriotic works. Putin’s explanation of the idea carries overtones of Great Russian nationalism and a rejection of the atomizing “Western” cult of the individual. A “subtle cultural therapy,” he wrote, shapes “a mind-set that binds the nation together,” inculcating “civic patriotism” and persuading people to take pride in being citizens of Russia.

So could the alarmists be right? Vladimir Putin is not an uncultured man. Behind the steely K.G.B. chic is someone who knows his poetry and enjoys quoting it. He recited lines from Pushkin to put down Georgia’s President Mikheil Saakashvili and astutely warned the upstart oligarchs a few years ago that if they didn’t toe the Kremlin’s line, they would end up like characters from “Eugene Onegin” — “some dead, and the rest far away.”

But Putin’s self-proclaimed role as arbiter of cultural taste has produced worrying moments. Last year he took it on himself to decide the future of Russian theater and public architecture in a Chairman Mao-like pronouncement (“We need theaters that will serve the people and further the education of the nation. Architectural constructions should not be large. . . . They should produce modern shows that are comprehensible to modern people”). And after taking his wife for a night out at a Moscow theater, he called in the director to discuss the right way to produce a play (“Why did you show the hero crying? The hero is a strong person. . . . You should not show him sniveling”), a lesson in presidential omniscience to which the director correctly replied, “You are absolutely right.”

For some Russians this is uncomfortably reminiscent of a famously categorical predecessor. Stalin, too, took a personal interest in cultural affairs, frequently telling authors, composers and directors how to do their jobs. The fate of great writers and artists would be decided by a laconic stroke of the leader’s pen in the margins of their police files. Isaak Babel, Osip Mandelstam and Vsevolod Meyerhold all got a fatal thumbs down, while Boris Pasternak (“Leave that cloud dweller in peace”) and Mikhail Bulgakov happily survived midnight phone calls from the man his colleagues described as “Genghis Khan with a telephone” quizzing them at length about the meaning of art.

Putin is not quite at that stage yet. And there has so far been no indication which 100 books will get the president’s seal of approval. But there are fears the old days of state selection will come back. After a brief flowering in the 1990s, Russia’s independent publishers have fallen on hard times. Bankruptcies have reduced their numbers, bookshops have closed and Internet publishing is still in its infancy. With only the state possessing the resources and the motivation to step unto the breach, the days of official literature could be closer to returning than we suspect.

Martin Sixsmith’s new book, “Russia: A 1,000-Year Chronicle of the Wild East,” is being published this month.

Traducere // Translate

Putin's Canon

Abonați-vă la:

Postare comentarii (Atom)

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu