For today’s post, we’re excited to present you with a rare testimony from one of the people fortunate enough to witness–and actively participate in–the creation of Stalker. Sergei Bessmertniy, which is more than likely his pseudonym, was hired as a mechanic to work on the set, and in this article he shares a lot of fascinating details about Stalker from a fresh, unique perspective. His account of the process of filming holds value mostly because of the little things, as the mechanic reveals how certain scenes were filmed, describes the footage that was lost or discarded, at the same time giving us hints and information that paint the picture of Andrei Tarkovsky, the filmmaker and charismatic individual. Our endless thanks goes to Anna Fokin, our friend and reader, who translated the text from Russian so that all of us can enjoy it. We hope you find it as interesting as we did. Update: “Due to the fact that in the Internet appeared the poor English translation of my memories about the filming of Stalker, I suggest a new one for which I thank my dear friends Yulia Shlapina and Alexandra Bondar.” —Sergei Bessmertniy

MY WORK ON THE SET OF ‘STALKER’

After military service, which was obligatory in the Soviet Union, I decided not to return to The Central Studio of Popular Science and Educational Films, where I used to work but get a job at Mosfilm (the oldest and biggest film studio in the Russian Federation), because I wanted to be in the world of cinema and I didn’t gave up hope on entering the VGIK (Russian State University of Cinematography) as a cameraman. In January 1977 I started working at that studio as a mechanic for servicing film-crew equipment and as an auxiliary technician. In contrast to the ordinary profession of mechanic repair there was the work on the set: installing a film camera, preparing a film stock to be operable, fulfilment the movement of the camera on a dolly or crane shot.Soon in the plan for a future filming I saw a name Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky. I had already known that he was a significant and extraordinary film director, but I had not read the book by Strugatsky. So the title didn’t mean anything to me, seeming very mysterious and intriguing. And of course, I was curious to know what kind of a movie it was. Sometimes I walked around the pavilion, where there was a decoration for the apartment of Stalker (where the first scene of Stalker was filmed at the beginning of February that year) but I didn’t see the filming itself. When I found out that there was an expedition organized to go to Estonia to continue filming, I asked my boss to appoint me there and she replied positively. As my work was of highly technical nature, there were no colleagues of mine who would treat the cinematography as a creation. Additionally, it was known that on the set of that director requirements for all members of the crew were usually higher and the work needed more effort. So thanks to that, I entered the film crew easily and without competition. Usually, on the set of a feature film the crew consisted of two mechanics; the first was a responsible one and the second was a helper. In that case I was the second one—a helper.

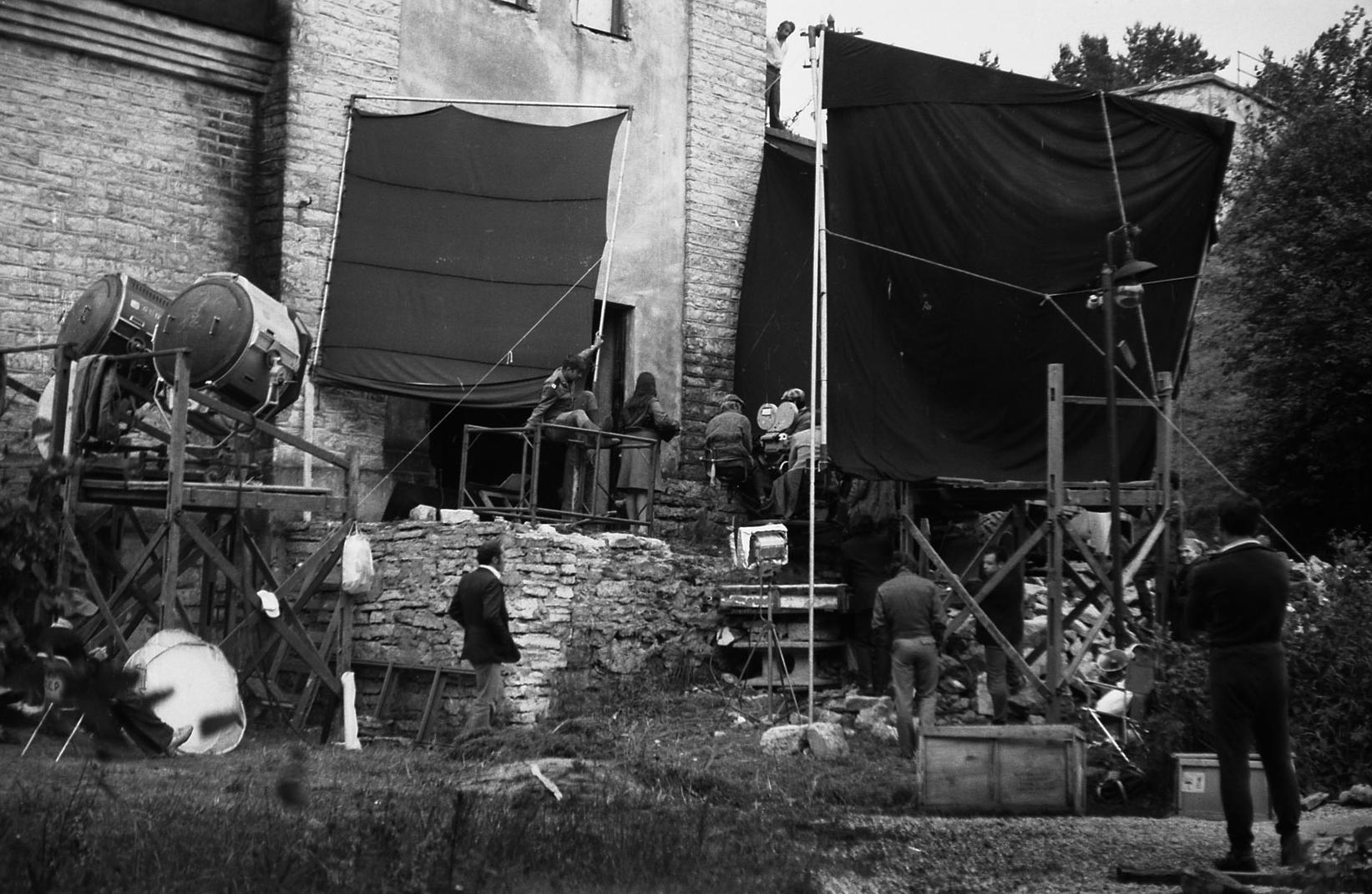

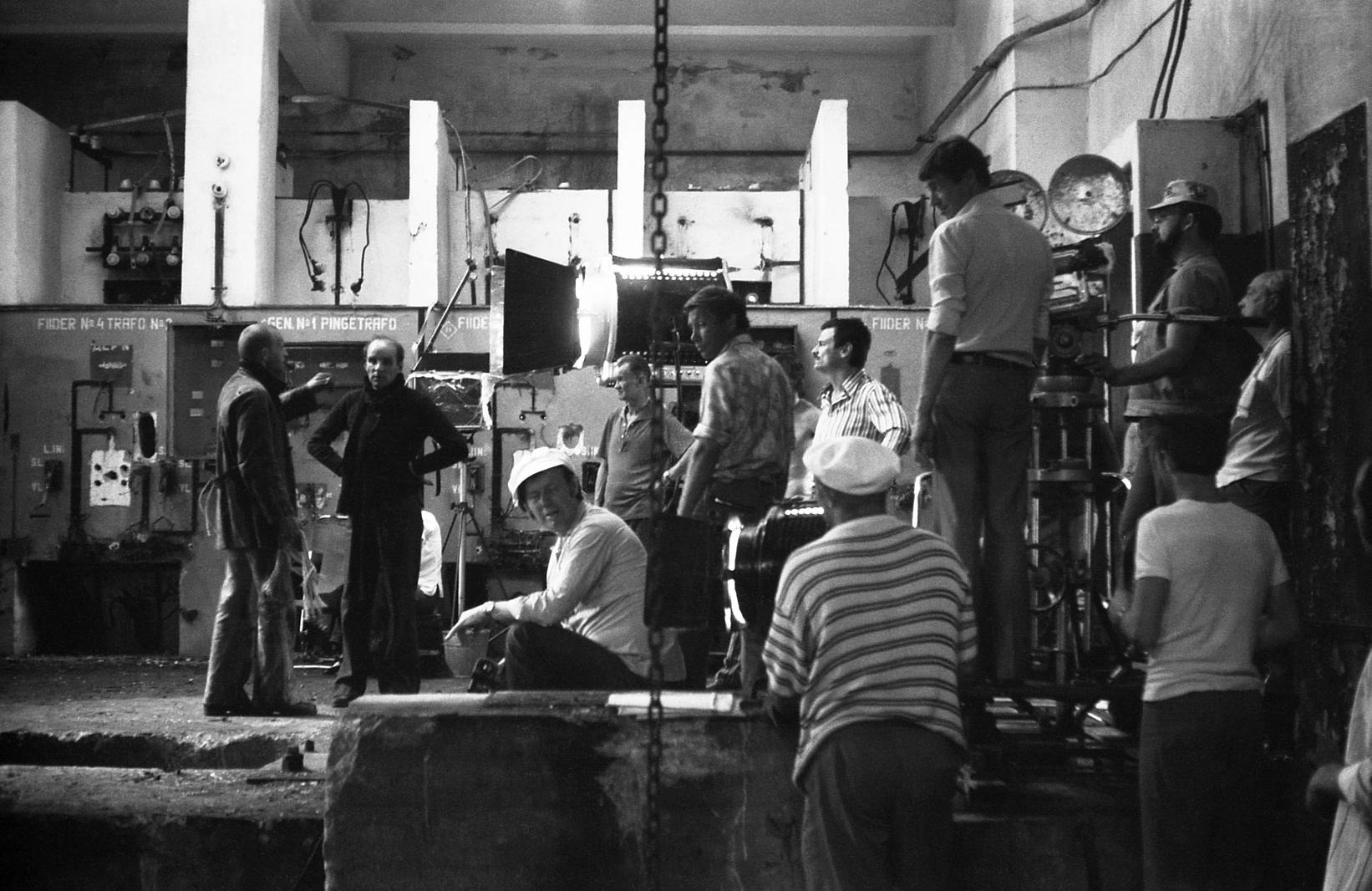

The filming took place at an abandoned power plant on the river Yagala (Jägala) in Estonia, as well as at the dam a mile away from it and at some sites in Tallinn. The power plant and dam had an expressive texture: cracked, lichen-covered concrete broken glass, oil stains. It seemed like artists, in preparation for the filming, just needed to follow this aesthetic.

Filming began in May. The first scene was the heroes’ approach to the building where the precious room was hidden. My colleague and I started to build a real railroad with turns for the dolly and carefully align it. All crew was warned that no one should walk on the grass which was supposed to be in the shot: everything should look untouched. It was the first time that I saw Tarkovsky. He was 45 years old, but I saw some youthful features in his guise He behaved in a quite simple manner and he often wore a denim suit.

Most of the scenes were filmed in the evening, in that short part of the day, when the sun had set behind the horizon, but it is still light. The director of photography Georgi Rerberg mostly didn’t illuminate the scene. He rather limited the light coming from the sky and put big black cloth shaders behind the camera or under the heads of actors, so that’s how the required lighting was achieved. Here with sometimes only a small light fixture worked. It slightly illuminated the actors’ faces below in filming close-ups. Thus, the quantity of light was at the limit of possibility.

We had been waiting for a few days when high-aperture lenses Distagon would arrive from Moscow that were needed for such conditions. Of course, we had to film with full open lens aperture (1,4) that created great difficulties for the focus assistant: there was almost no depth of field in close-ups. Actually Rerberg preferred to use lenses with constant focal length and also camera geared head. Camera was old: the american Mitchell NC. Without doubt Rerberg was one of the best masters in the country at that period.

The birth of this film was difficult. I was not aware of the intricacies of the creative process, as a technical worker, but I had known already that at that time hardly the first version of the script was used. The characters were not the same as in the final version. For example, in the film there is an episode where the Writer hits the Stalker’s face but then filmed the scene in which the assertive and aggressive Stalker hits the Writer. For the imitation of blood the old cinematic trick was used: someone was sent to find cranberry jam, which Tarkovsky liked more than the composition that was made at the studio. The script still had some sci-fi effects which showed the Zone’s strangeness that were later almost discarded by Tarkovsky. There were a lot of nuts thrown from a bandage, but the meaning of the action wasn’t explained. One of these nuts is hanging on the wall in my room for many years. There was an episode filmed where a lamp (which was hanging on the pole) suddenly lit up brightly and then burnt out. In the finished version of the film that lamp was displayed in another episode.

On another episode, the writer got into a place where he suddenly started to become very wet and moisture simply flowed from him, and then it quickly evaporated. For filming this effect was created a system of branched rubber tubes, which Solonitsyn had to wear under his coat so at the right moment the water had to gush out quickly. Making a wet footprint on the iron sheet was created with the help of acetone and a blowtorch.

There was also a dialogue between characters at the power plant. It had to be filmed with a moving camera that, unnoticed by the audience, passed into the reflection of the mirror. And then the viewer suddenly had to see that scene in the mirror-inverted form. A different game with space was expressed in the shot, which was built on the dam. Between the rails on which the camera dolly stood lay a mirror with still-life painting of a moss and sand that depicted a landscape from bird’s eye view.

Moreover, the mirror looked like the surface of the pond with the sky’s reflection. A camera, looking above, floated over it then passed into the water and, rising, went out on the real river landscape. This was one of the two shots that were filmed in the first filming period and then included in the final version of the film. However, the start of the shot was cut off and the game effect with space was gone. This motif was then heard in the next two films of Tarkovsky.

The second shot remaining in the film was a view of the river completely covered in a reddish foam and several flakes whirled with wind in the air. It was not a special effect: the waste of pulp and paper was dumped into this river from an industrial complex and the water was very dirty. However, oddly to say, there were small fish. A few years later, when it turned out that most of the members of the crew had passed away, rumors appeared that it was because the area around the place of filming had been poisoned. Some say it might have been radiation, but I don’t know any specific facts about it.

In addition to the fact that the script was constantly changed, some scenes of the film had to be reshot again. It seemed strange to me: if they were not Tarkovsky and Rerberg, but someone less known, I would have suspected them of incompetence.

The footage was taken away to Moscow for developing and feedback came a few days later. I was in the first viewing at the “Tallinn-film” studio. The image looked dark and greenish.

These are two shots from that first footage.

In the future, viewing the footage took place privately. Then I thought: “Well, this is a rough positive, later will be printed, as it should.” But everything turned out to be more complicated. I found out later about the creative problems, but meanwhile the second cameraman who was responsible for exposure had to leave the crew, but I doubt very much that he was guilty. Then the same did production designer Alexander Boim—an experienced artist of theater and cinema. They began to replace one or the other member of the crew. On one fine day my turn came—without any explanation they told me that I had to leave for Moscow. So I did. I had an impression that the initiator of all this leapfrog was not Tarkovsky, but someone from his surroundings. My bosses at the studio had no issues to me, I guess, they understood that it was some kind of a game. In the end Rerberg also had to leave. Instead of him was invited Leonid Kalashnikov, who came with his own assistants. They filmed something and then the work stopped—the autumn had come.

I continued to work at the studio, took part in the filming of the movie Yemelyan Pugachev held in Belarus. Meanwhile, the fate of Stalker was decided.

It was agreed that the reason of the failure was a defective batch of the film (Kodak 5247) and wrong film development.

It seems strange to me, because all that had to be seen before filming at the stage of trial. They had managed to arrange the film as a two-part film so funds were found for the continuation of filming. The script was changed again, and it was decided to re-shoot it all over again.

1978

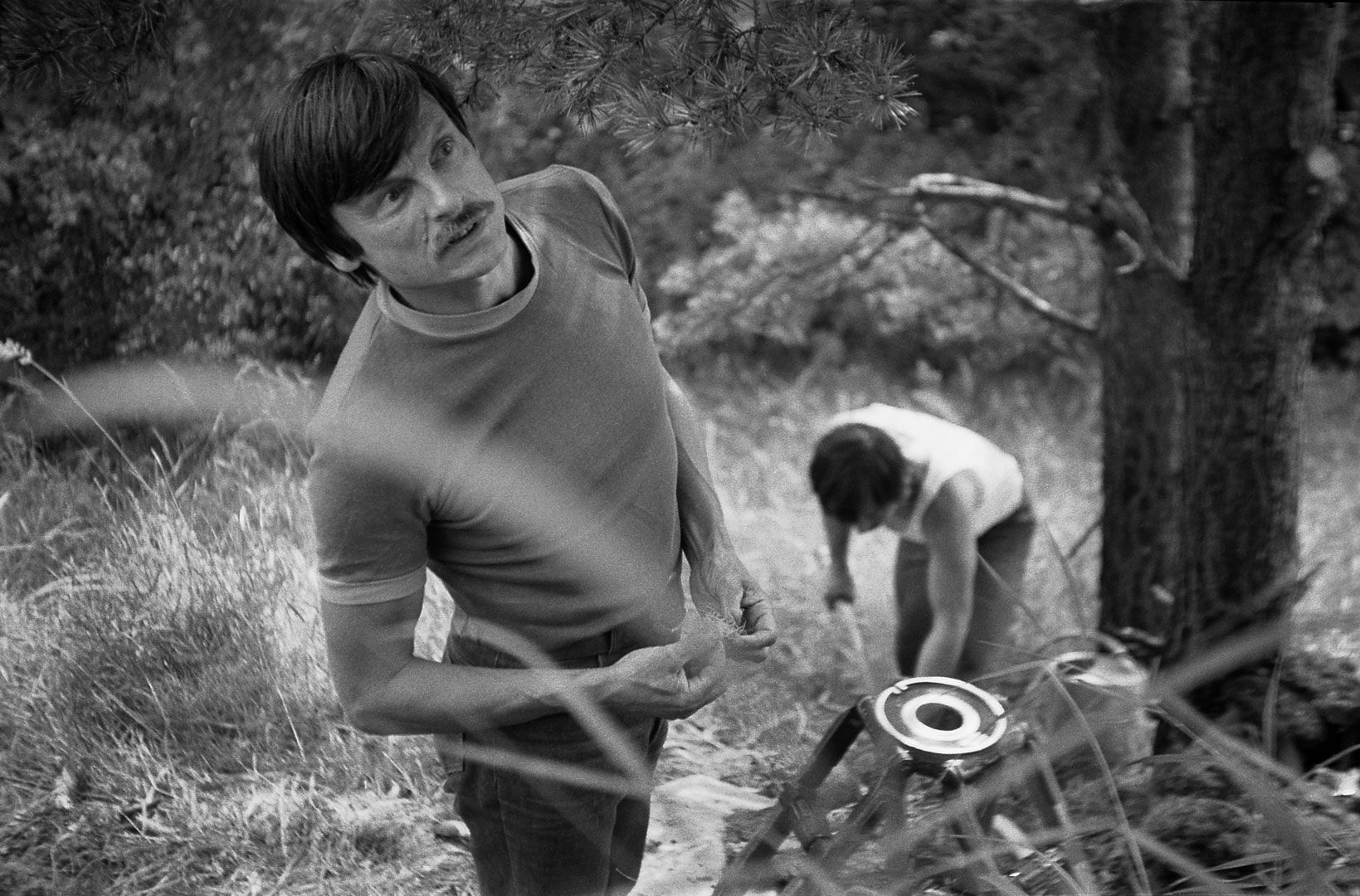

The work had to be resumed in the spring at the same objects again and the assistant of the cameraman invited me to join the camera crew. Alexander Knyazhinskiy was now the director of photography. He was a good master, but, in my opinion, he didn’t feel as independent as Regberg did and that was the reason he felt an internal stress. Now we used a film camera KSN, which is a Soviet copy of the american camera Mitchell NC and almost all films except close-ups in the scene of travel in the Zone were filmed by zoom lens Cooke Varotal (20-100, T 3.1). It is a high-quality English lens with a variable focal length; the size of it was as big as an artillery shell and it cost the same as a passenger car. I was still a second mechanic, but the first one, more experienced, who worked at the studio for about 20 years, had noticed that I was a hardworking person so he gave me the opportunity to work on my own. And actually I’m really thankful for it. In Tarkovsky’s films the camera often moves long and slow. On the set of Stalker, in most cases, I had to make this movement.

And we’re in Estonia again. We started with the arrival scene in the Zone when the film’s heroes stop the handcar and continue on foot.

In the distance we see the abandoned military equipment. Part of that was real and was brought specially from Moscow, the rest was made by decorators. Before the filming a pyrotechnist was running with a smoke pot, keeping an eye on the wind direction and creating the effect of fog.

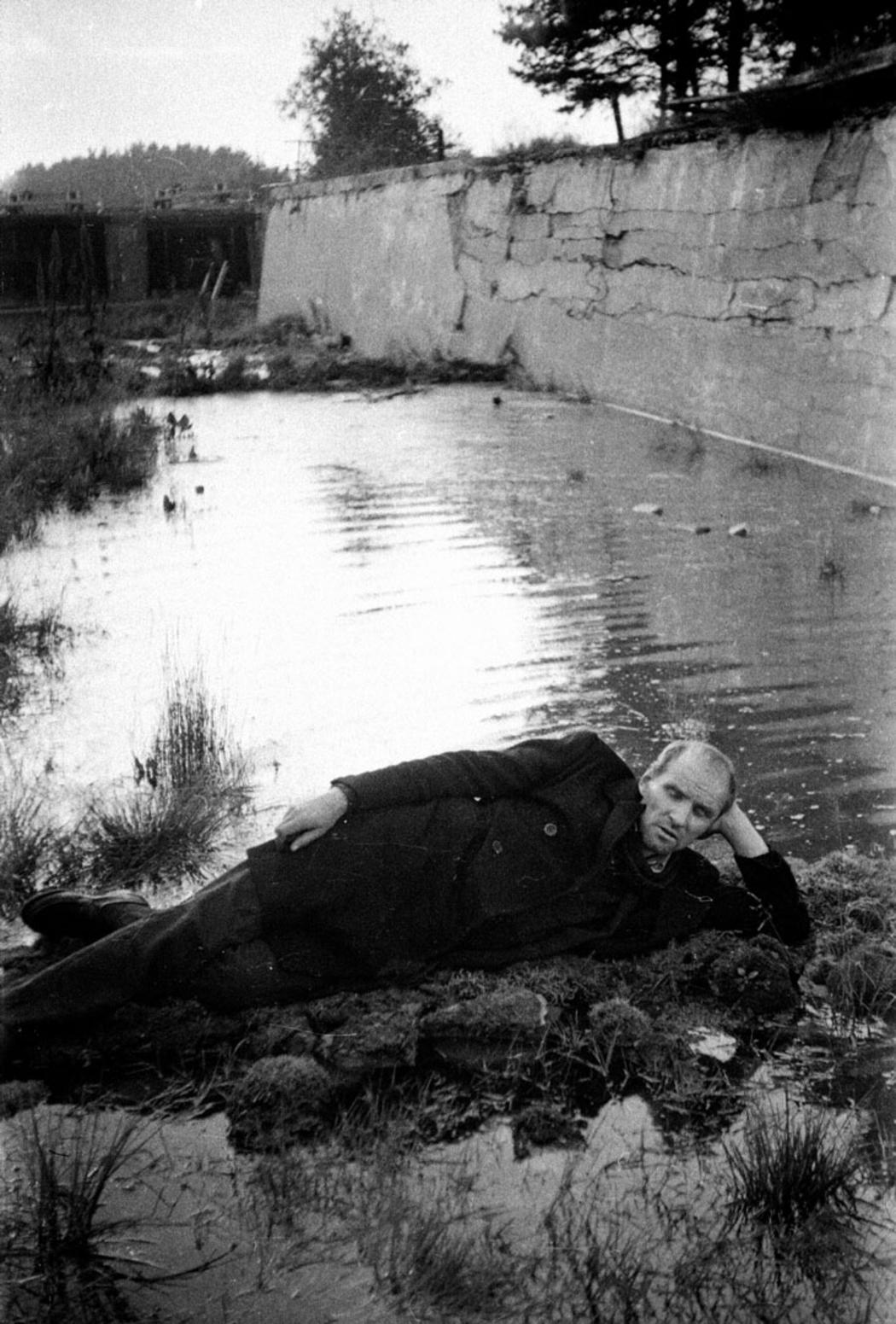

Near the power plant a memorable scene of the film was shot when the camera from a close-up of a lying Stalker moves to water with lying objects in it and floats over. At this time in the finished version of the film we hear a woman’s voice reading a fragment of the Apocalypse (6.12-16).

00:00 / 00:00

Andrei Tarkovsky shooting "Stalker"

Now Playing

It happened at the bottom of a small canal that used to pour water on the turbine of the power plant. At this time the water was about ankle deep. Kajdanovsky was almost lying in the water, even though there was something put under him. The weather was quite chilly and the costume designer Nelly Fomina came up with an idea: the actor should wear a waterproof and heat-insulated suit for divers under his clothes. So that’s how he wasn’t able to get cold.

The rails were placed on each side of the actor and dolly with camera was placed in an unusual way: the right-hand wheels on the right rails and the left on the left and the actor was under it.

The film camera was mounted on a lawest tripod at the edge of the dolly looking down on the actor. When, during filming, it passed over him, he got up and moved to a new place where the camera saw him in the final shot. I remember how Tarkovsky asked me: “Sergei, could you drive this distance in 3 minutes?” I said, “Let’s try.” He started his stopwatch and gave me “Action” command. I slowly began to roll the dolly and count seconds in my head.

Generally people of my profession were assistants of сinematographer and could not talk to the director at all. But as far as Andrei Tarkovsky took full part in the filming process and in rehearsal he often took the place of the operator behind the camera. So I can confidently say that I have worked with him.

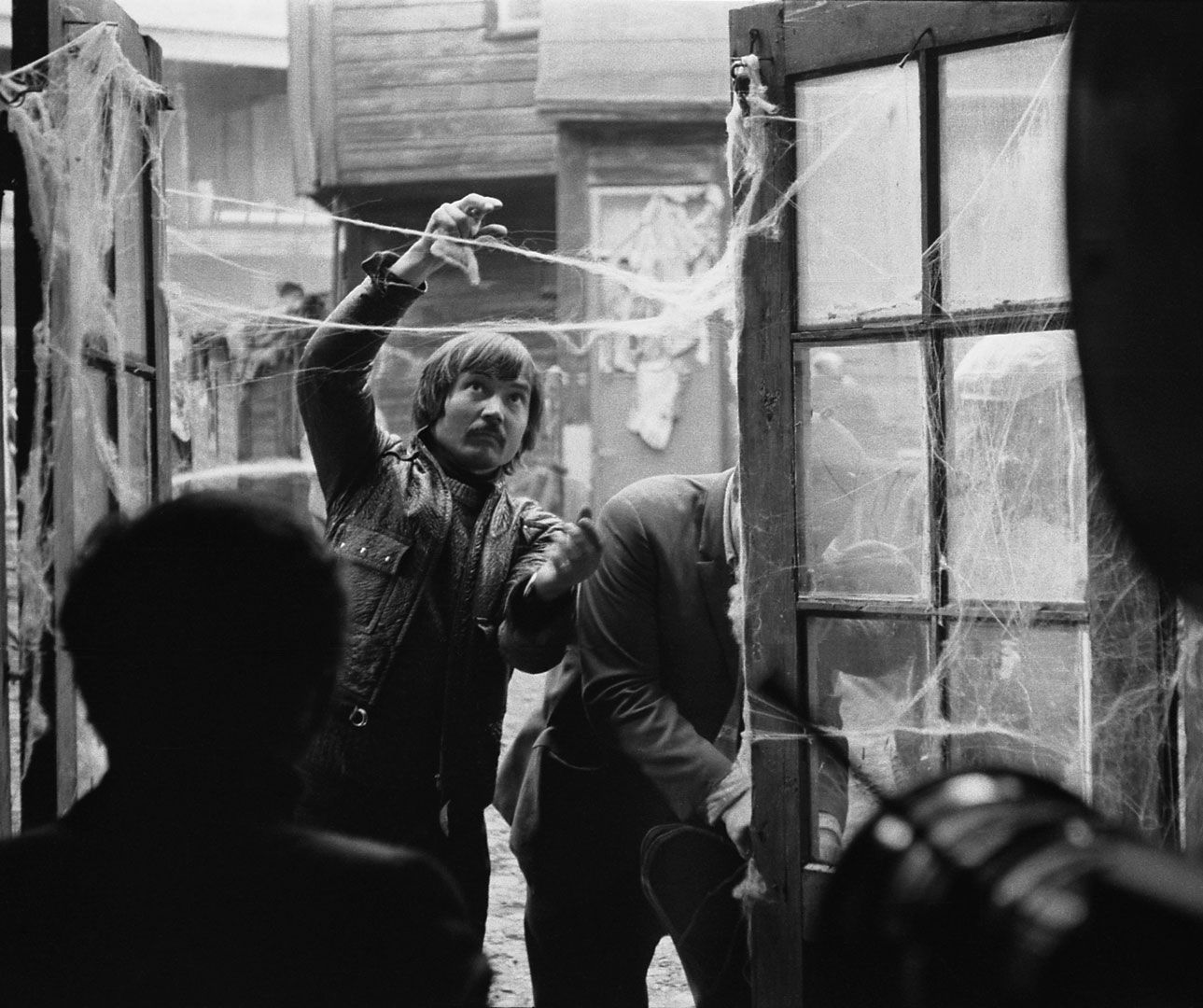

Also, he actively participated in the work of decorators, paying attention to every detail in the picture. “Make an ikebana for us!” he joked.

The indefatigable helper of director in the preparation of every shot was an artist from Kazan called Rashit Safiullin.

Sometimes the filming took place in cool weather. “Without Kaif no Life,” once said Solonitsyn lying during rehearsal on wet moss, surrounded by water, as it was required by the episode. For all of the group he was named Tolia; Kajdanovsky was Sasha; Grinko was Nikolai Grigoryevich, apparently in order of seniority.

Water was a favorite theme of Tarkovsky, and there was a lot of it. Sometimes we had to wear rubber boots on a wooden tripod.

The filming process mostly consists of expectations and despite the tense situation there was time for rest, for example, for playing dice or for conversations about something extraneous. I remember that one day Tarkovsky said that he loved the genre of western and that he would gladly film something like that. I think if he had been filming a Western, it would have been similar to the prologue of the film Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Generally he was supercritical, for example, he said once that Spielberg’s films were not cinema at all (perhaps he meant Jaws). I did not join this conversation, but I remember that I didn’t agree with him. In my opinion, a film can be good in different ways—Spielberg is good in his own way, Bergman in his.

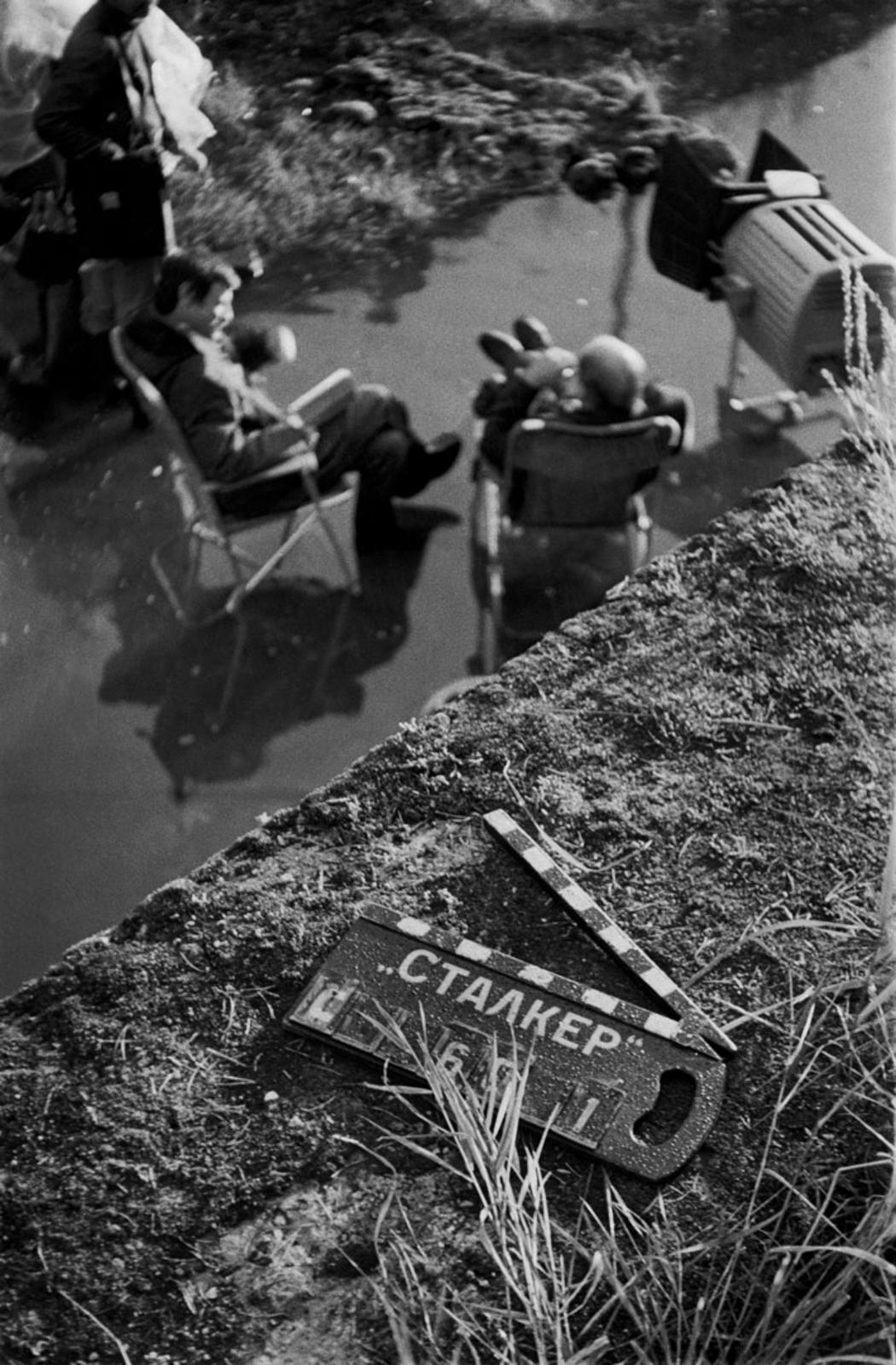

There was a Mosfilm staff photographer Vladimir Murashko (now deceased) who worked on the set from the very beginning until the end of filming; during 1977 and 1978 he captured each and any meaningful frame of the film as well as some work moments in the shooting process. He had a high-quality 6X6 cm Hasselblad camera. But among all the shots from the filming which I found in books, periodicals and Internet only a few could be presumably attributed to his authorship. It would be interesting to know where the rest of the materials went.

I filmed quite a few good frames. At that time I had not yet sufficiently defined the tasks as a person with a photo camera: what should generally be filmed? In addition to the most interesting moments, I was usually busy with my main work, also because of the tense situation during filming I felt uncomfortable to be active in this matter.

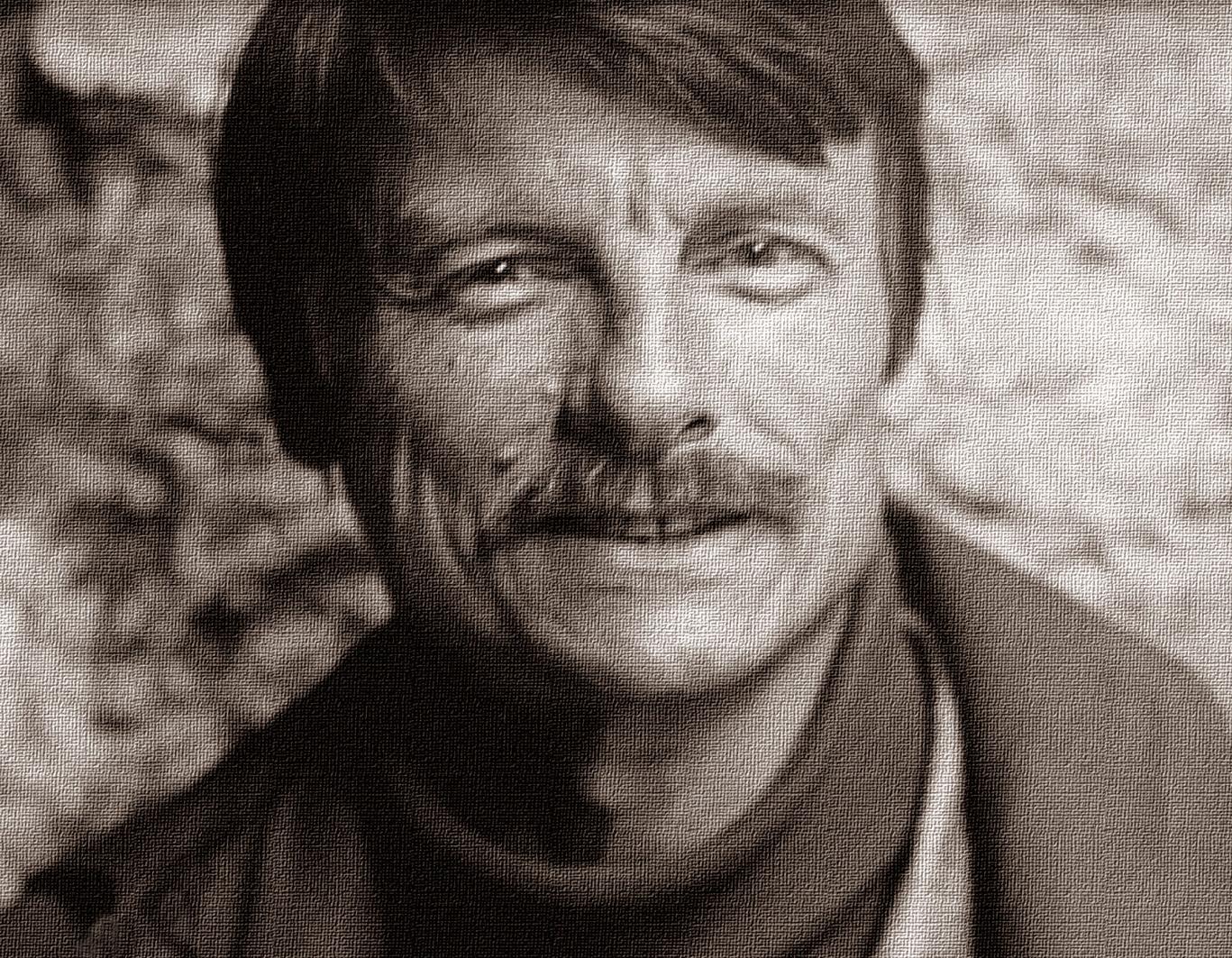

I had the Zenit 3M camera for 35 mm film and an old german Voightländer with bellows for the glass plates 6×9 cm and I also tried to take pictures with it. Once Tarkovsky noticed it and told me that his father had the similar. Talking with him I said, “Well, let me to take a photo of you with this camera.” I asked him to take a step back to get away from the direct sun and then I made the photo. It turned out without sharpness and for many years I thought it wasn’t a good one. Then after scanning the negative and setting in Photoshop, I thought, “Not in sharpness is happiness—he was smiling and looking at the viewer, I have not seen another shot like that.”

Some working moments in Estonia were filmed with a movie camera. I’ve never seen this footage. I wonder where it is.

That scene, where the characters sit on the handcar and drive off, was filmed in Tallinn in an abandoned oil storage. In the episode where they pass into the Zone the police should appear. They had conditional uniforms chosen so it should be unclear in which country the action took place. If you look more closely, you can see that on their helmets one can see connected letters “AT” and actually it was the initials of the director. The same letters can be seen on a pack of cigarettes that are smoked by Stalker’s wife.

Close-ups during the passage into the Zone were filmed in another industrial outskirts of the city. Actors were sitting not on the handcar, but the railway platform, which was rolled along the rails by a locomotive. The rails for the dolly were placed next to them, on which a cameraman sat, holding an Arriflex camera that was equipped with the stabilizer system Steadycam, quenching its shaking and jerking, and thus providing a smooth movement. I moved the dolly which allows the camera to switch from one actor to another.

There was a scene where characters drive a Land Rover and rush into Zone through the gate of UN to follow a locomotive that carries a platform with electro-ceramic insulators. It was quite comic. Tarkovsky (who was overcoming the noise of the locomotive) explained through the megaphone to a driver that he should move when he waves his hand. At the same time he was showing how he would do it. But the driver didn’t hear all the words and drove off. Tarkovsky shouted: “No, no, not now, during filming!” The locomotive was stopped and, panting heavily, returned. Tarkovsky started to explain it again, but that time without showing. Suddenly the locomotive began to move again. Confused, Tarkovsky turned to his colleagues: “I did not wave!” It turned out that, behind him, his assistant Eugene Tsymbal was showing the driver the gesture.

In the film that shot is black-and-white. In General, all filmed on color film, but some scenes were printed in black and white.

In Moscow (at Mosfilm) in the big pavilion a large complex was built with decorations that depicted Stalker’s apartment and also some of the Zone’s places which were created in a special way that allowed to fill them with water.

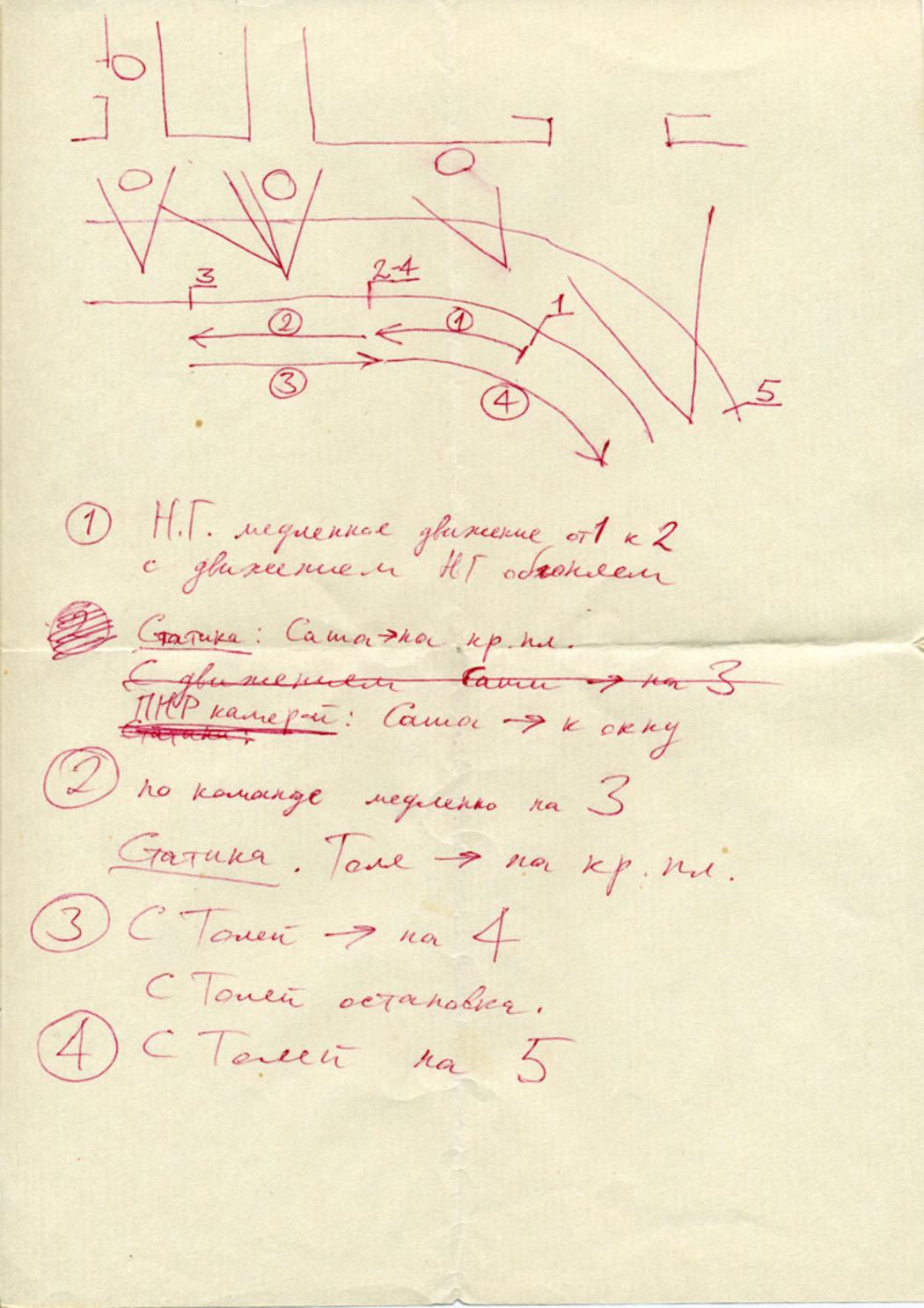

There is a long scene when Stalker reads a poem “So the summer is over,” and starts a dialogue and meanwhile a phone rings and a lamp turns on. The dolly with camera a few times moved on rails with a twist. As between the rehearsal and filming there were two or three days off, I had to draw the movement of the dolly for the only time in my practice. In the end, this scene was shortened during the film editing.

Other decorations depicted a curved tunnel where characters should go. For moving the camera a special dolly was created which was moving on rails, fortified on both sides of the tunnel, and closed by long stripes decorated canvas, which was raised to allow for the dolly rides.

00:00 / 00:00

Stalker - tunnel scene

The whole scene was filmed in the pavilion.

Then these decorations were removed and new ones were built: a room in the Zone where wishes came true and lots of hills, similar to the graves, and the interior of the bar.

I remember when we were shooting a dialogue between Stalker and his wife just before his departure to the Zone which resulted in her hysterics, Alisa Freundlich got so deep into the state of her character that she was unable not get out of it immediately after a stop command, and Eugene Tsymbal literally carried her in his arms behind the scenery.

During filming at Mosfilm Garik Pinkhassov came on set with his camera, having previously worked at the studio as an camera assistant, and later becoming a famous photographer. Also, Vladimir Vysotsky, well known singer-songwriter, poet and actor, who was a friend of Tarkovsky, once visited the set.

The only scene that was shot on location in Moscow is the exit from the bar. A small decoration was built near the fence of Psychiatric Hospital named after Kashchenko and grim industrial landscape in the background. You can see pipes of the Heating Plant-20 (Vavilova Street 13).

A deep sense of the film opened to me gradually, not even at first view. I think during filming it was hardly understood by anyone moreover the concept of the author didn’t take shape right away.

Text: Sergey Bessmertniy © 2014

Selected photos: © Sergei Bessmertniy, George Pinkhassov

Production still photographer: Vadim Murashko © Mosfilm, Vtoroe Tvorcheskoe Obedinenie

RERBERG AND TARKOVSKY: THE REVERSE SIDE OF ‘STALKER’

This account of cinematographer Georgi Rerberg’s career and his creative turmoil with Andrei Tarkovsky on Mirror and Stalker, though disputed, provides a fascinating window into the making of the films and the artistic process and personalities of the individuals involved. The film is a visual feast—a collage of on-set footage, production stills, paintings, personal reminisences, home movies and interviews.

00:00 / 00:00

Rerberg and Tarkovsky: The Reverse Side of 'Stalker' (2009)

‘STALKER’: THE ZONE OF ANDREI TARKOVSKY

On the shooting of Stalker, about Andrei Tarkovsky, and the actors who played in the film.

Open YouTube video

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), meticulously restored and looking better than ever, on Mosfilm’s YT channel.

This May at the Film Society, experience the mysteries and revelations

of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 science fiction masterpiece in a new digital

restoration. Twenty years ago a falling object decimated a provincial

Russian town, and those who later went near the crash site—now known as

The Zone—disappeared. Access is strictly prohibited, but outsiders can

still get in with the help of a “stalker.” Inside The Zone is The Room,

within which secret wishes can be granted. Based on the novel ‘Roadside

Picnic’ by the Strugatsky brothers, Stalker is a visually

extraordinary and philosophically provocative fable about the limits of

knowledge—personal, scientific, and spiritual. New digital restoration

by Mosfilm. A Janus Films release.” —The Film Society of Lincoln Center

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu