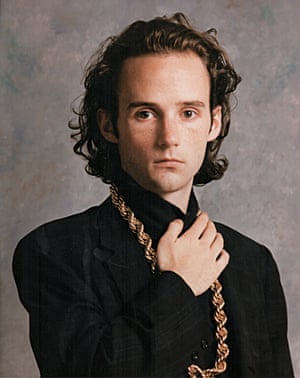

Before I picked up Moby’s new memoir, Porcelain, I thought of him as a small, bald, cheeky chappy who made tuneful dance music. I knew he had a few unconventional beliefs (wasn’t he vegan? Hardcore Christian? Maybe teetotal?), but filed him as essentially harmless. After reading Porcelain, well… Let’s just say his book is packed with incident. Lots of dodgy sex, oceans of alcohol, antics a-gogo. Plus: cockroaches, raves, death, celebrities (from Madonna to Robert Downey Jr, but not in starry situations) and good old Top Of The Pops. It’s a romp of a book. Such outrageous fun, in fact, that Moby tells me he’s noticed that people have regarded him differently after reading it.

“They have a look,” he says. “It’s odd being on the receiving end of that look. It’s a look of knowing, but it’s also a look of concern. Like, ‘Is everything OK?’”

The fact is, his book makes me like Moby more. For a start, he writes brilliantly, with none of the self-indulgence of most pop memoirs: “I wanted each chapter to be like an anecdote you’d tell in a bar, to have a punchline,” he says. And also, there’s something touching about who he was back then. At one point, he writes this, about some club kids – “They were all doing obscene amounts of drugs and having sex with strangers, but they still seemed innocent” – and that’s exactly how he comes across. “It’s quasi-Dickensian,” he says. “Naive boy from the country moves to the big city and things go wrong.”

We are drinking herbal tea and eating (very tasty) vegetables in Moby’s newly opened vegan restaurant in blue-skied Los Angeles. It’s a nice place and I am relaxed, but endearingly, Moby isn’t. He picks up a fallen cushion and plumps it before putting it back on the bench; he asks me if I’m too cold and alters the air con; he goes through the menu with me.

Moby has lived on the west coast for six years, but had no problem transporting himself back to his past for the book. Sometimes he would be writing about being blind drunk in New York, “covered in filth and squalor”, and look up from his laptop and be shocked to see his swimming pool, bathed in sunshine. “The writing felt true and the reality felt like fiction. It was like time travel.”

Let’s zoom back in time with him, then. Porcelain concerns itself with Moby’s life between 1989 and 1999, from when he moved to New York to just before the release of Play, his fifth album, and the one that changed everything. Play was packed full of sample-heavy, catchy dance tunes, which buried themselves into everyday life. Even if you haven’t actively listened to the album, you’ll know the songs: Honey, with its driving piano riff and Bessie Jones sample “get my honey come back, sometimes”; Natural Blues, featuring another blues sample (“oh lordy, trouble so hard”), this time from Vera Hall. (Moby sourced these samples, and others, from Alan Lomax’s folk music field recordings.) Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad? has featured on the GSCE syllabus for music since 2008. Anyway, the big thing about Play was that every single one of its tracks was subsequently licensed for advertising or films. This was a huge deal at the time, and a huge deal for Moby. It moved him from the electronica shadows into the big league, changed him from a musician who scrabbled for a few thousand dollars to a fully fledged, in-the-spotlight, pop star overlord. For a while, Moby was dance music’s Adele: everyone liked his stuff.

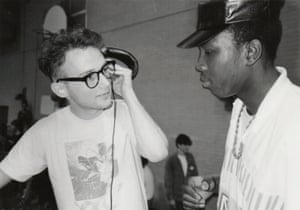

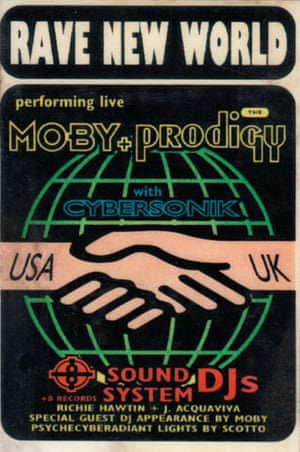

None of this is hinted at in his memoir, however, because none of it was foreshadowed in real life. In real life, before Play, Moby was bumping around New York, getting DJ gigs in now legendary clubs like Mars and Nasa, as well as awful swingers’ nights (he says he would play anywhere). His career, as careers do, took time. In 1992, he had success with one track, Go (particularly in the UK, where we have always been more open to his music than the US) and made a few well-received albums.

Then, in 1995, just at the moment dance music really crossed over, he blew whatever small chance he had by bringing out a thrash punk LP.

He is funny about this and his musical work is all present and correct in Porcelain, but it takes second place to the more fascinating everyday happenings in his life. He’s a dominatrix’s sidekick (he calls himself Master Bobby and shouts at a businessman wearing fuchsia lingerie). He gets Lyme disease, he dates indie girls and strippers; he lives in disused warehouses and crappy flats with weirded-out flatmates who want to set him on fire and buy the petrol to do so.

What is strange is how he chose to compartmentalise his life. He bounced between out-there clubbers and the suburban devout, between hanging out in orgies and having a mostly unconsummated relationship with his Christian girlfriend (they would hand out vegan sandwiches to homeless people for thrills). He was monastic in his home habits, then would go out and socialise madly. He was a vegan, sober, nonsexual God-botherer partying in the blood-soaked Meatpacking District with the sex-and-druggers. In 1995, after being teetotal for eight years, he took up drinking again. There’s a sort of relief in it. He had so many different personae to try to unite.

Is he still like that?

“Hmm. I still recognise that person, stumbling through life without much agency. There’s enthusiasm and a good work ethic, but ultimately complete cluelessness, being baffled by everything. It’s like being a snowball rolling down a mountain. The snowball might have started kind of pure, but by the end, it’s filled with dead squirrels and sticks and rocks and wellies and garbage. You’ve got this snowball at the end, but to what extent does it relate to or resemble that original snowball?”

Moby, as you see, does a good line in therapy talk (“Well, we’re in southern California, the land of veganism and therapy,” he says), but he’s also very funny.Salman Rushdie has given a glowing quote for the cover of Porcelain that references Moby’s supposed ancestor Herman Melville (hence Moby, after Melville’s Moby-Dick; his real name is Richard Melville Hall). He has started writing the next instalment, covering the 10 years post-Play. He says his publishers, so far, don’t approve. They think his excesses make him too unsympathetic. Such as? “Oh, fame, money, degeneracy, debauchery, bottoming out,” says Moby. What’s not to like? “I know! That’s what I want to read in a book!”

Because it focuses on his life from 23 to 33 years old, Porcelain doesn’t take on Moby’s childhood. Still, tellingly, it opens with a scene concerning him and his mother. She is working in a laundromat, unhappy, furious, and he is sitting in the car, waiting for her to finish her shift. He is 10. He tells me he could have written a lot more about his young life – “there are maybe five memoirs in there” – and he clearly had a tough time. His father died in a drink-driving accident when Moby was just two. His mother’s family was wealthy (Moby’s grandfather ran a successful Wall Street company), but she rejected her background and set off to make her own story. “Sometimes we would be living in a squat-ish house with three or four other drug-addicted hippies, with bands playing in the basement,” he says. “Which sounds fun, but when you’re in fourth grade trying to do homework and there are people smoking pot in the kitchen, or fighting…” Every so often, they would stay with his grandparents in wealthy Darien, Connecticut, which was nice, but made him feel poor and ashamed.

In the second half of the book, his mum dies of cancer, and there’s an awful – almost unbelievable – incident that happens around her funeral. “I remember it so clearly,” Moby says. “Someone had left a digital alarm clock at my house, and it was the most reliable thing in the world, and the alarm was as clear and easy to use as a digital clock can be. And so, the night before my mom’s funeral, I set the alarm. But this completely reliable clock at some point was set forward 21 hours, which meant that if it were 3am it somehow got set forward to midnight. The only thing that could have happened is that, at some point during the night, I woke up in a fugue state and set the clock forward 21 hours, so I would miss her funeral… I must have set it forward 21 hours, because something in my subconscious said that was the only legitimate and expedient way to miss the funeral.”

I ask him how he feels about that now, and his eyes mist up a tiny bit. He is sad: not for himself, but for his family. “She was my mom, but more importantly in some ways she was my aunts’ sister. And my grandmother’s daughter. I feel guilty. But for myself, I don’t know.”

Not knowing how you feel about things is a protective instinct. Moby is a lovely companion, in real life and on the page, but he can seem detached from his emotions. When his mum told him she had cancer, she also told him that he has a half-brother. I ask him about this, assuming he would have got in touch. But no.

“If it were a full brother, then that would be interesting, but it’s a half-brother,” he says. (“It”!). “In terms of my genetic sequence, I have almost as much in common with you and most of the people in this restaurant as I would with a half-brother.” And that’s that.

What Porcelain suggests is that Moby’s greatest love back then wasn’t his family, or a person, or even music, but a city. At heart, Porcelain is a love letter to old New York: that grubby, crumbling, dangerous place. Recently, Moby was describing it to some young friends, and they couldn’t believe what he was describing; honouring the city of that time was a major motivation in his writing. “New York completely changed in those 10 years. In 1989, it was old New York… cheap, murder-y, dysfunctional, fires… and by the end of the 90s, it was Jay Z and bottle service and condos.”

It took Moby a long time to fall out of love with New York, but he did. He gave up drink and his love ended. “I was walking up Orchard Street, and it was one of those shitty days, 36 degrees Fahrenheit, sleeting, grey snow, and I realised there is sometimes an elective quality to suffering.” New York suited his drinking; he classifies himself as “an old-timey alcoholic, I mean, there’s just no doubt, you know?” He would try going out for a couple of drinks and find himself “at 8am, with strangers in my house, bags of drugs, I’d had about 15 drinks, having sex with a complete stranger. Which is great, but that was my best attempt to drink in moderation. Also, I thought I was going on these great adventures, and the truth is I was going from one bar to another on Ludlow Street.”

So he got sober and moved to LA. For a while, he lived in Marlon Brando’s old house, the fabulous Wolf’s Lair, an actual castle, but it soon felt too big. Now he’s in a three-bedroom place: his musical equipment is in one bedroom, his exercise stuff in another, and he sleeps in the third. Hardly Jay Z, but he seems happy.

In the past few years, Moby has reassessed his life. He wants to carry on making music – he has an album coming out this year – but he doesn’t want to tour. He’s happy for people to pay for his music, but he doesn’t mind giving it away and, to this end, has set up a website so that student filmmakers can use his albums as soundtracks for free. He’s stopped caring what other people think of him (not much social media, just occasionally posting on Instagram, mostly cute animals or nature scenes). And he’s decided that animal rights are his life’s work.

“That’s my day job – animal rights,” he says. “Making music and writing books and doing other things is what I love, and it’s fun, but I don’t see it as work. You know, a lot of activism is single-issue activism. Like say, someone campaigns about turning land into a park. There’s the land, you turn it into a park, it benefits the community – that’s good. But it’s limited. But the thing with animal agriculture, everything is covered by it. There’s the animal side of it: most people who are not sociopaths can agree that animal suffering is not a good thing. But then there’s the climate change aspect, the rainforest deforestation, famine – the reason there’s famine is because food that could be fed to humans is fed to animals instead – then heart disease, diabetes, cancer, erectile dysfunction… Animal activism is my life’s purpose. If someone came to me and said if I could die, and my death would somehow serve the purpose of saving animals, I’d do it in a heartbeat.”

Then of course, there’s the restaurant, which he finds a constant trial. “Everything has to be perfect. I’m an emotional perfectionist – I just want things to feel as good as they possibly can for the people who are experiencing them.”

He did have another vegan restaurant, in New York, called TeaNY, which he opened in 2002, with his then girlfriend. This was a disaster, as they split up soon after, and, though they’re still on good terms, he doesn’t seem to know if TeaNY is still going. Relationships don’t appear to be Moby’s forte: he hooks up with a couple of women in the book who seem great, but he can’t make it last. Was he just a sex dog? “I don’t think I was driven by sex. The way I dated was motived by the desire to be validated in someone’s eyes. And clearly the desire to have sex as well, but it was like seeking validation without attachment or obligation.”

He also thinks his difficulties with his mum had an effect. “If you’re constantly ashamed when you’re growing up, when you become an adult you’re constantly ashamed. And when you get close to people you assume they will only like you as long as they see you in your best light. There is the profound desire for closeness and the profound fear of the other person. You start getting close to someone, they do something that might not be perfect, and it triggers a terror response and you run away… By you, I mean me, of course.”

Anyway, he’s been in a relationship for eight months now, his first in 10 years. It seems to be going OK, though he can’t really tell. He calls himself a “developmentally disabled space alien or robot” and he keeps having to ask his girlfriend things: “Like, is it OK if I go to bed after you do?” He’s also pretty set on not having children. He says, “if the person I’m dating got pregnant, sure – I’d happily be involved and help out as much as I possibly can, but it’s not something I long to do”, which is about as detached as you can get without running away. He’s going to adopt a couple of dogs after he comes back from his book tour, he thinks. He seems able to feel great emotion for humanity and animals in general, but finds it harder one-on-one.

We talk a little bit about his Christianity; towards the end of the book, he starts questioning it, and he says now that he still understands the desire for spirituality, just not institutionalised belief systems or “ideological rigidity”.

“I don’t think that God cares what jersey you wear,” he says. “It’s not like Man United and Leeds… is that the right UK sports reference?”

Leeds aren’t in the Premiership any more.

“OK, Arsenal? Man United and Arsenal: that tribal rivalry is really fun in sport, but I don’t think it should be part of divinity.”

We are having a laugh now; I feel as though I’m talking to a friend. Moby is quite the most low-key multimillionaire I have ever met. He is modest. He looks the way he always did: unflashy with his shirt over a T-shirt, creative casual, unrich. He hasn’t even had his teeth done, which is almost prosecutable in LA. We talk a bit about money and he says he thinks materialism doesn’t work, meaning it doesn’t actually make anyone properly happy. He should know, of course.

Moby seems to be enjoying his life, now he’s not spending a big part of it drunk. “I love reading and travelling to interesting parts of the world, and having time to think and write and make music and do activism. Life is short, and we have a limited amount of time and energy, and it’s just so much easier trying to be your honest self.”

I take the opportunity to ask him about a long-standing rumour. Supposedly, years ago, Moby and his friends would play a prank at parties. One of them would unzip his flies and hang his willy out of his trousers, then the others would challenge him to go up to someone famous and “knob touch” them. I ask him if this ever happened, or if it was made up.

“It’s both,” he says, and pauses. “Hmm, there’s a funny side to this story. I might change it because I don’t know if I want it to follow me around. I had some friends from college who would do that. They would get very drunk, pull their willy out and just brush it up against people. Because it was funny. So what I will say is that a friend of mine once did that to Donald Trump.” I laugh. “It was a restaurant on Park Avenue around 20th Street, some fundraising event, when Trump was just a New York real-estate developer.”

You seem to remember it well. Did that person get extra kudos for Trump?

“You can extrapolate as to who that person might be, and that’s as much as I can say,” says Moby, a man who can’t resist a funny anecdote, who’s happy to tell the truth, who has lived a full and full-on life – but who is old enough now to know that he doesn’t want all the consequences that come wrapped in the adventures. Fair enough. As long as he keeps writing all those stories down, we’re good.

Extract from the book

Iwas flying to London for the third time in two months in 1991, to play a show for Kiss FM and to perform on Top Of The Pops. Go, this oddball song that I recorded on a few hundred dollars’ worth of equipment, was now a Top 10 hit in the UK.

The record company had sent a car to pick me up from Heathrow. After two hours in traffic, we pulled up to the hotel. Except it wasn’t a hotel. It was a sad grey house on a sad grey road in a defeated part of London.

Eric, my new manager, met me outside the house. He and I had met in New York a year ago and I’d asked him to be my manager, even though he hadn’t ever really managed anyone. He was tall, German, and seemed trustworthy. “Welcome to sunny England!” he said in the drizzle.

“Is this the hotel?” I asked.

“It’s a B&B; my office is nearby. It seemed like a good choice,” he said.

We walked in and I got my key from a woman in the entranceway. She was wearing a worn beige dress and reading the Daily Mirror. “Here’s your key,” she croaked. “Your room’s on the second floor and the bathroom’s down the hall.” She handed me a towel that had clearly been used in the second world war to mop up diseased blood from the basements of infirmaries.

“OK, pop star,” Eric said. “I’ll pick you up at one.”

“OK, I’ll just take a shower,” I said.

“Shower’s 50p for five minutes.”

I was confused. The shower cost money?

“You put 50p in the shower and you get five minutes of water,” she said brusquely.

***

That evening, Eric and I drove to the Astoria. My dressing room was a small closet with a black plastic chair and two bare lightbulbs over a mirror. “It’s just as depressing as your hotel,” Eric the German comedian said. “You should feel right at home.”

I looked at the running order. “I play for 10 minutes?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Eric said. “You play Go, and then maybe play Go again.”

Eric and I walked up to the stage. The show was in an old, venerable theatre but it felt like a rave. The crowd was waving glow sticks and blowing air horns and whistles. On stage, Dream Frequency were playing their hit Feel So Real. The stage was full of singers, dancers, and keyboard players. The song sounded amazing and I was petrified.

The MC said, “Now from New York, Moby Go!” I had got used to being introduced as “Moby Go”: because of the design of my single’s sleeve many Britons thought “Moby Go” was my name.

I ran on stage. The crowd roared, but I panicked because my keyboard wasn’t plugged in and I didn’t even have a microphone. They didn’t care: 3,000 people were dancing and yelling “Go!” at the top of their lungs. I banged on my unplugged keyboard and yelled “Go!”.

The song ended and the MC returned. “Wicked! Top tune from Moby Go! Next up are Manchester favourites K-Klass!” Some roadies ran on stage, grabbed my keyboard, and rushed it off stage. I stood there, confused. Wasn’t I supposed to play a second song?

“Come on, mate, get off the fucking stage!” one of the roadies barked at me. I scurried off.

“But my keyboard was unplugged and I didn’t have a microphone and what about my second song?” I asked.“That was great!” Eric said. “They loved it!”

“Oh, they’re running behind schedule so they’re cutting people’s second songs. They told me while you were on.”

I considered that. “The song was OK?” I asked.

“It was amazing! Didn’t you see the crowd?”

“But I wasn’t really doing anything.”

“It doesn’t matter. They loved it.”

I hung out and watched the rest of the show: Orbital, 808 State, the Prodigy. It was like listening to my record collection. After the show, Eric dropped me back at my alleged hotel. It was 1am and I had to be up at 8.30 for Top Of The Pops. Sleeping would be wise, but I was now wide awake. I went for a walk.

I walked for a mile or so before it started to rain. The only shops open were Pakistani grocery stores: little beacons of light on the wide empty streets. I came to an overpass and looked at the railway lines beneath me. Why was this city so quiet? Growing up, I’d imagined London to be like Times Square, with every inch a riot of noise and activity. I thought of a Clash lyric in London’s Burning, “I run through the empty stone because I’m all alone”, and it made sense.

I’d grown up seeing two different Englands on TV. There was the bucolic England with witty university students floating on slow boats on gentle rivers and sunny ponds. Then there was this England, the rainy, cold England that was the background for every movie about defeated people waiting to die in public housing estates. This was the country that gave birth to Joy Division. If Ian Curtishad been born in Palo Alto he’d probably be managing a chain of organic coffee shops and married to a yoga teacher.

My shoes were getting squishy from the rain. I walked for another hour and got back to my hovel. It was 5am and I had to wake up in three hours. There was a thin grey light coming through the curtains. I kept my clothes on, got under the one smallpox-ridden blanket, and willed myself to sleep.

***

“Pop star! It’s your big day! Wake up!” It was Eric, yelling on the other side of the door. I was already dressed, so I put on my damp sneakers.

When Sally from the record company showed me my dressing room at the BBC I almost started crying with joy. It was small, but it had a radiator and was warm. Most importantly, it had its own bathroom and its own shower.

I took off my stinky travel clothes and stepped into the shower for 10 uninterrupted minutes. The water was hot, and for the first time in days, I was clean. I dried off and lay down on the couch. The rain was pattering against the old windows, the steam heat was clanking in the old radiator, and I felt at peace. I closed my eyes, and there was a knock on the door. “Moby? First run-through in five minutes!”

“No,” Eric said. “Some people sing live, but everyone mimes their equipment.”I climbed on to the tiny stage where I’d be performing. None of the gear was plugged in. “Do they plug in the equipment before the broadcast?” I asked.

I looked across the room: New Orderwere rehearsing on their stage. I’d loved Joy Division obsessively and loved New Order just as much. Now they were standing 40 feet away from me. When it was my turn, I stood behind my unplugged equipment and jumped around a bit and yelled “Go” into the unplugged microphone.

Three naps and two rehearsals later, Sally came to my dressing room. “Do you have your clothes ready?” she asked.

I was going to wear a pair of yellow pants that I’d found at a Salvation Army shop and a green T-shirt covered in arrows. I thought it looked cool and futuristic, possibly like something Marinetti would have worn if he’d been a balding techno musician and not an aspiring fascist.

I stepped out of the dressing room and Eric guffawed. “That’s what you’re going to wear?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said defensively. Sally looked concerned.

“The guys from a club called Rush gave you a T-shirt if you want to wear it?”

I took off my futuristic arrows shirt and put on the proffered Rush T-shirt.

“Much better,” Eric said. “You look almost modern.”

We walked into the TV studio for the live broadcast and the energy was completely different from the rehearsals: the lights were flashing, all the musicians were dressed up, and the studio was filled with audience members. My song started. I jumped around, banged on my keyboard, yelled, “Go!” and whacked the Octapad. And in three minutes, before I even knew what was happening, it was done. I was hurried off my little stage by a stagehand and walked down the hallway and back to my dressing room.

A moment later, Eric came in. “How was that?” I asked.

“It looked good, but maybe next time you want to dance a little less?”

“You think so? But what should I do?”

“I don’t know, just play keyboards and hit the drum machine.”

“OK,” I said, slightly chastened.

***

I took off my futuristic yellow pants and my Rush club shirt and stepped into the shower. The adrenaline left me and I deflated like a balloon. None of this made sense to me. What was I doing here? Living in an abandoned factory in a crack neighbourhood made sense to me. Playing punk rock shows for 10 people in a dingy bar made sense to me. Walking around New York dropping off cassettes at record labels made sense to me. But flying to England and being on TV shows confused me to the core of my soul. Top Of The Pops was New Order’s world. It was Phil Collins’ world. I loved it, maybe too much, but it wasn’t my world.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu