How symbols become symbols, or what keeping atoms in harmony has to do with language acquisition.

BY MARIA POPOVA

Novelist and philosopher Umberto Eco once said that the list is the origin of culture. But his fascination with lists and organization grew out of his longtime love affair with semiotics, the study of signs and symbols as an anthropological sensemaking mechanism for the world. In bridging semiotics with literature, Eco proposed a dichotomy of “open texts,” which allow multiple interpretations, and “closed texts,” defined by a single possible interpretation. Since semiotics is so closely related to language, one of its central inquiries deals with language acquisition — when, why, and how children begin to associate objects with the words that designate those objects. Most children’s picture books, with their simple messages and unequivocal moral lessons, fall within the category of “closed texts.”

Novelist and philosopher Umberto Eco once said that the list is the origin of culture. But his fascination with lists and organization grew out of his longtime love affair with semiotics, the study of signs and symbols as an anthropological sensemaking mechanism for the world. In bridging semiotics with literature, Eco proposed a dichotomy of “open texts,” which allow multiple interpretations, and “closed texts,” defined by a single possible interpretation. Since semiotics is so closely related to language, one of its central inquiries deals with language acquisition — when, why, and how children begin to associate objects with the words that designate those objects. Most children’s picture books, with their simple messages and unequivocal moral lessons, fall within the category of “closed texts.”

In 1966, Eco published The Bomb and the General (public library) — a children’s book that, unlike the “open texts” of his adult novels with their infinite interpretations, followed the “closed text” format of the picture book genre to deliver a cautionary tale of the Atomic Age wrapped in a clear message of peace, environmentalism, and tolerance. But what makes the project extraordinary is the parallel visual and textual narrative reinforcing the message — the beautiful abstract illustrations by Italian artist Eugenio Carmi contain recurring symbols that reiterate the story in a visceral way as the child learns to draw connections between the meaning of the images with the meaning of the words.

This particular page presents a lovely wink at Brian Cox’s The Quantum Universe, featured here earlier today:

Mom is made of atoms.

Milk is made of atoms.

Women are made of atoms.

Air is made of atoms.

Fire is made of atoms.

We are made of atoms.

The Bomb and the General is a fine addition to these little–known but fantastic children’s books by famous authors of adult literature.

via the lovely We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie; images courtesy of Ariel S. Winter

UMBERTO ECO: THE BOMB AND THE GENERAL

WHEN I FIRST STARTED WE TOO WERE CHILDREN, MR. BARRIE, one of the things I hoped to examine was the way in which an author accustomed to writing for adults conceived of writing for children. Why? Because, as many authors included on the blog have noted, childhood reading is often the reading that is most influential on a writer (or on any individual). Consequently, if a writer who is aware of the importance of childhood reading writes what he hopes will be an influential text for the next generation, how does what he includes in that text reveal what he thinks is most important to literature?

This question takes on new meaning when it comes to the works of Umberto Eco, an author who so understands the influence of childhood reading that he wrote an entire novel,The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2005), in which the main character seeks to define his very identity from the books and comic books of his youth. Eco, most famous for his novel In the Name of the Rose (1980), first rose to prominence in academic circles as a Medievalist, philosopher, and semiotician.

Semiotics is the study of signs and their meanings. This includes the way in which words signify actual objects. For example, we call an apple by the word "apple," but a physical apple does not actually contain the word "apple." How then, does the word "apple" relate to the physical object? In what way does the word "apple" cause people to relate to the object? And how does the word "apple" function in a variety of contexts? These questions are of special importance when dealing with children, because children are only just learning about the world, and a lot of that learning is done through language acquisition. So, to a baby, the object apple is simply an observable object. But through language acquisition, it acquires the sign "apple." And as the child ages, the sign "apple" also comes to encompass secondary contextual meanings, say New York City's nickname "The Big Apple," or the symbolic meaning of an apple in the Adam and Eve story. Since so much of this learning comes from books (think of all of the "My first word..." books, which are simply photographs of objects paired with the relevant word), a semiotician writing a children's book, would not only bring concerns of its literary impact, but also of its linguistic, semiotic impact as well.

Semiotics is the study of signs and their meanings. This includes the way in which words signify actual objects. For example, we call an apple by the word "apple," but a physical apple does not actually contain the word "apple." How then, does the word "apple" relate to the physical object? In what way does the word "apple" cause people to relate to the object? And how does the word "apple" function in a variety of contexts? These questions are of special importance when dealing with children, because children are only just learning about the world, and a lot of that learning is done through language acquisition. So, to a baby, the object apple is simply an observable object. But through language acquisition, it acquires the sign "apple." And as the child ages, the sign "apple" also comes to encompass secondary contextual meanings, say New York City's nickname "The Big Apple," or the symbolic meaning of an apple in the Adam and Eve story. Since so much of this learning comes from books (think of all of the "My first word..." books, which are simply photographs of objects paired with the relevant word), a semiotician writing a children's book, would not only bring concerns of its literary impact, but also of its linguistic, semiotic impact as well.

Which brings us to Umberto Eco. Almost. Eco's major contribution to semiotics is in the application of semiotics to literature. Eco expostulated the theory of "open texts" and "closed texts." An "open text" is one that allows multiple interpretations. A "closed text" dictates one interpretation. It is a question of whether a whole sequence of signs, the words and sentences that make up a story, can have different meanings than the signs usually have. Children's books, picture books in particular, are usually "closed texts." They have a specific message that is dictated to the child, a moral or lesson a child is supposed to take away from the story. Despite the myriad of interpretations his adult novels invite, Eco's picture books are no exception. They preach peace, understanding, and environmentalism.

Are you still with me? It's almost story time. I promise. Let's just go back a paragraph for a moment.

Remember the "My first word..." books? Picture = word, right? Eco's books seem at first to almost take that approach. All the books are done in two page spreads. The page on the left contains nothing but text. The page on the right contains nothing but a picture. But the picture is often abstract (see the "atom" in the spread on the left). These books don't teach words. They are highly representational. But the books' messages are closed, dictated, and even the abstract images contribute to that effect.

How? For that I must direct you to the article by Maria Truglio, Wise Gnomes, Nervous Astronauts, and a Very Bad General: The Children's Books of Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi, in Children's Literature, Volume 36, 2008, which is where I got pretty much all of my much watered-down version. Basically, while the illustrations Carmi uses are abstract, they contain their own recurring symbols--follow those little atom circles up above and the general to the right as we go forward. Those symbols then reiterate the story, reinforcing its message.

And of my original question, what do all of these concerns reveal about Eco's idea of literature? I'll let you decide.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN ITALIAN IN 1966, The Bomb and the General is the first of Eco and Carmi's three picture books. Revised and reissued in 1988, the books received English translations (by William Weaver, the translator of most of Eco's novels), which Truglio notes in her essay, are sometimes interpretations of the original text in a way.

"Once upon a time there was an atom."

"Once upon a time there was an atom."

"And once upon a time there was a bad general who wore a uniform covered with gold braid."

Atoms are the building blocks of the world. "Mom is made of atoms. Milk is made of atoms." And when all of the atoms are in harmony, then life is good.

But when atoms are broken, "A terrifying explosion takes place! This is atomic death."

But when atoms are broken, "A terrifying explosion takes place! This is atomic death."

Well, the atom had been put in a bomb, and the general had a lot of bombs. "'When I have lots and lots,' he said, 'I'll start a beautiful war!'"

"How can you help but become bad when you have all of those bombs within reach?"

"How can you help but become bad when you have all of those bombs within reach?"

The atom, along with his fellow atoms, don't want to blow up the world and cause death and destruction. So they sneak out of the bombs, which are in the attic, and hang out in the cellar.

Finally, goaded by his financial backers, the general does declare war. He loads the bombs onto airplanes and starts dropping them.

The people begin to run around in a panic. "But where could they find refuge?"

But the bombs sans atoms, don't explode, and everyone is happy, and they realize life is better without war. They decide to never make war again.

"And what about the general?" He becomes a doorman at a hotel "to make use of his uniform with all the braid." Everyone treats him as a lowly menial, even people who once had to obey him, and the general is embarrassed. "Because now he was of no importance at all."

TO SEE MORE OF THE BOMB AND THE GENERAL, check out my Flickr set here. And anyone who wants to correct my discussion on semiotics or to extend it, please do. I am by no means an expert.

This question takes on new meaning when it comes to the works of Umberto Eco, an author who so understands the influence of childhood reading that he wrote an entire novel,The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2005), in which the main character seeks to define his very identity from the books and comic books of his youth. Eco, most famous for his novel In the Name of the Rose (1980), first rose to prominence in academic circles as a Medievalist, philosopher, and semiotician.

Semiotics is the study of signs and their meanings. This includes the way in which words signify actual objects. For example, we call an apple by the word "apple," but a physical apple does not actually contain the word "apple." How then, does the word "apple" relate to the physical object? In what way does the word "apple" cause people to relate to the object? And how does the word "apple" function in a variety of contexts? These questions are of special importance when dealing with children, because children are only just learning about the world, and a lot of that learning is done through language acquisition. So, to a baby, the object apple is simply an observable object. But through language acquisition, it acquires the sign "apple." And as the child ages, the sign "apple" also comes to encompass secondary contextual meanings, say New York City's nickname "The Big Apple," or the symbolic meaning of an apple in the Adam and Eve story. Since so much of this learning comes from books (think of all of the "My first word..." books, which are simply photographs of objects paired with the relevant word), a semiotician writing a children's book, would not only bring concerns of its literary impact, but also of its linguistic, semiotic impact as well.

Semiotics is the study of signs and their meanings. This includes the way in which words signify actual objects. For example, we call an apple by the word "apple," but a physical apple does not actually contain the word "apple." How then, does the word "apple" relate to the physical object? In what way does the word "apple" cause people to relate to the object? And how does the word "apple" function in a variety of contexts? These questions are of special importance when dealing with children, because children are only just learning about the world, and a lot of that learning is done through language acquisition. So, to a baby, the object apple is simply an observable object. But through language acquisition, it acquires the sign "apple." And as the child ages, the sign "apple" also comes to encompass secondary contextual meanings, say New York City's nickname "The Big Apple," or the symbolic meaning of an apple in the Adam and Eve story. Since so much of this learning comes from books (think of all of the "My first word..." books, which are simply photographs of objects paired with the relevant word), a semiotician writing a children's book, would not only bring concerns of its literary impact, but also of its linguistic, semiotic impact as well.Which brings us to Umberto Eco. Almost. Eco's major contribution to semiotics is in the application of semiotics to literature. Eco expostulated the theory of "open texts" and "closed texts." An "open text" is one that allows multiple interpretations. A "closed text" dictates one interpretation. It is a question of whether a whole sequence of signs, the words and sentences that make up a story, can have different meanings than the signs usually have. Children's books, picture books in particular, are usually "closed texts." They have a specific message that is dictated to the child, a moral or lesson a child is supposed to take away from the story. Despite the myriad of interpretations his adult novels invite, Eco's picture books are no exception. They preach peace, understanding, and environmentalism.

Are you still with me? It's almost story time. I promise. Let's just go back a paragraph for a moment.

Remember the "My first word..." books? Picture = word, right? Eco's books seem at first to almost take that approach. All the books are done in two page spreads. The page on the left contains nothing but text. The page on the right contains nothing but a picture. But the picture is often abstract (see the "atom" in the spread on the left). These books don't teach words. They are highly representational. But the books' messages are closed, dictated, and even the abstract images contribute to that effect.

How? For that I must direct you to the article by Maria Truglio, Wise Gnomes, Nervous Astronauts, and a Very Bad General: The Children's Books of Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi, in Children's Literature, Volume 36, 2008, which is where I got pretty much all of my much watered-down version. Basically, while the illustrations Carmi uses are abstract, they contain their own recurring symbols--follow those little atom circles up above and the general to the right as we go forward. Those symbols then reiterate the story, reinforcing its message.

And of my original question, what do all of these concerns reveal about Eco's idea of literature? I'll let you decide.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN ITALIAN IN 1966, The Bomb and the General is the first of Eco and Carmi's three picture books. Revised and reissued in 1988, the books received English translations (by William Weaver, the translator of most of Eco's novels), which Truglio notes in her essay, are sometimes interpretations of the original text in a way.

"Once upon a time there was an atom."

"Once upon a time there was an atom.""And once upon a time there was a bad general who wore a uniform covered with gold braid."

Atoms are the building blocks of the world. "Mom is made of atoms. Milk is made of atoms." And when all of the atoms are in harmony, then life is good.

But when atoms are broken, "A terrifying explosion takes place! This is atomic death."

But when atoms are broken, "A terrifying explosion takes place! This is atomic death."Well, the atom had been put in a bomb, and the general had a lot of bombs. "'When I have lots and lots,' he said, 'I'll start a beautiful war!'"

"How can you help but become bad when you have all of those bombs within reach?"

"How can you help but become bad when you have all of those bombs within reach?"The atom, along with his fellow atoms, don't want to blow up the world and cause death and destruction. So they sneak out of the bombs, which are in the attic, and hang out in the cellar.

Finally, goaded by his financial backers, the general does declare war. He loads the bombs onto airplanes and starts dropping them.

The people begin to run around in a panic. "But where could they find refuge?"

But the bombs sans atoms, don't explode, and everyone is happy, and they realize life is better without war. They decide to never make war again.

"And what about the general?" He becomes a doorman at a hotel "to make use of his uniform with all the braid." Everyone treats him as a lowly menial, even people who once had to obey him, and the general is embarrassed. "Because now he was of no importance at all."

TO SEE MORE OF THE BOMB AND THE GENERAL, check out my Flickr set here. And anyone who wants to correct my discussion on semiotics or to extend it, please do. I am by no means an expert.

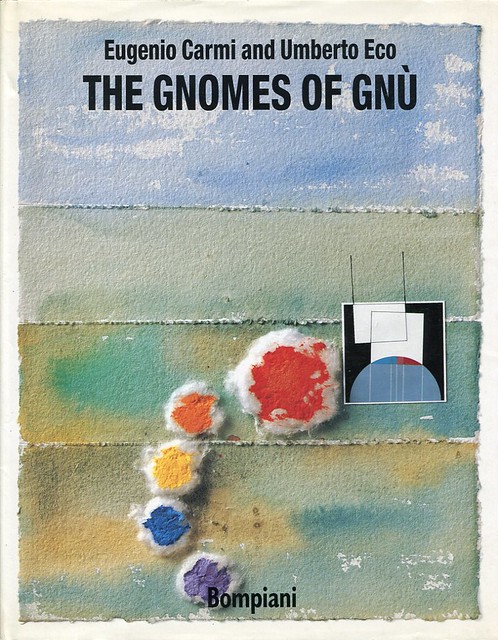

UMBERTO ECO: THE GNOMES OF GNÙ

A LITTLE OVER TWENTY-FIVE YEARS after they published their first two children's books, Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi published the ecological parable The Gnomes of Gnù. Like in the earlier works, The Gnomes of Gnù carries a heavy-handed message, in this case that we should work on cleaning up the earth. But unlike The Bomb and the General and The Three Astronauts, The Gnomes of Gnù lacks a clear protagonist that undergoes some kind of change meant to represent the change we should all make to improve the world. There is a protagonist, the Space Explorer (called SE throughout), but he functions simply as a lens that focuses on all of the ecological horrors that plague the earth: smog, oil spills, deforestation, not to mention drug abuse and automobile accidents, not quite ecological, but still a problem. He's willing to then be the messenger of change, but not through any conviction, simply because, why not? As a result, the book isn't that compelling, which is perhaps why it is so scarce. Only five libraries hold the English edition worldwide according to WorldCat.

"ONCE UPON A TIME there was on Earth -- and perhaps there still is -- a powerful Emperor, whose greatest desire was to discover a new land." His ministers have to inform him that all of the land on Earth has been discovered, and that space exploration is the future of discovery. So he sends out a Space Explorer, SE, to find a beautiful planet to which they can bring civilization.

After combing "the immensity of space for a long time," finding only barren rocks and spitting volcanoes, SE finally finds an inhabited planet: Gnù.

The gnomes of Gnù come out to meet SE, and SE tells them he's discovered them. They say that they discovered him, but they won't quibble over the matter, "otherwise we'll spoil our day." SE says he's come to bring them civilization. The gnomes ask what civilization is.

The gnomes of Gnù come out to meet SE, and SE tells them he's discovered them. They say that they discovered him, but they won't quibble over the matter, "otherwise we'll spoil our day." SE says he's come to bring them civilization. The gnomes ask what civilization is.

"'Civilization,' SE answered, 'is a whole lot of wonderful things that Earth people have invented, and my Emperor is willing to give it all to you free of charge.'"

The gnomes require more of a definition than this, so SE pulls out "his megalactic megatelescope and trained it on our planet."

That's where, somewhat embarrassed, SE has to admit that Earth has smog, oil spills--"'You mean your ocean is full of shit?' the second gnome asked, and all the others laughed, because when somebody says 'shit' on Gnù, the other gnomes can't help laughing.'"--, litter, deforestation, traffic jams, automobile crashes, disease from smoking, intravenous drug abuse, and motorcycle accidents. The gnomes are understandably not interested in receiving civilization.

That's where, somewhat embarrassed, SE has to admit that Earth has smog, oil spills--"'You mean your ocean is full of shit?' the second gnome asked, and all the others laughed, because when somebody says 'shit' on Gnù, the other gnomes can't help laughing.'"--, litter, deforestation, traffic jams, automobile crashes, disease from smoking, intravenous drug abuse, and motorcycle accidents. The gnomes are understandably not interested in receiving civilization.

"'Listen, Mr. Discoverer, I've just had a great idea. Why don't my people go down to Earth and discover you?'" The gnomes can then teach everyone to take care of meadows, gardens, trees, to collect litter and end pollution, and to walk instead of drive.

SE just says, "'All right then..I'll go home and talk about it with the Emperor.'"

At home, the ministers aren't going to let the gnomes come without the proper papers. Then one of them trips on chewing gum and is grievously injured, thus changing the subject.

"For the moment our story ends here. We're only sorry we can't add that everybody lived happily ever after." Let's just hope we can do on our own what the gnomes would have taught us.

TO READ THE GNOMES OF GNÙ in its entirety, you can view it as a Flickr set here. To answer your question, yes, the book actually uses the word "shit."

THE THREE ASTRONAUTS

FOR UMBERTO ECO AND EUGENIO CARMI'S FIRST PICTURE BOOK, The Bomb and the General, they tackled the Cold War arms race. For their second, The Three Astronauts, also released in 1966, they turned to the Space Race. It had been only five years since Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in April of 1961, and the Cold War battle between the USA and the USSR to be the first nation to conquer space was still very present, with both nations setting sights for the moon. Like Eco and Carmi's first book, The Three Astronautspreaches pacifism, but with more of a focus on multiculturalism. It takes the same storybook tone as The Bomb and the General, trying to cast the Space Race in the language of fable.

"ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS EARTH.

"ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS EARTH.

"And once upon a time there was Mars."

The people of Earth want to explore Mars. They send up rockets that fall back to the ground. Then they send up rockets that go out into space. Then they send up a dog in a rocket, "but the dogs couldn't talk, and the only message they sent was 'bow wow.'" So they finally send up a man.

"One fine morning three rockets took off from three different places on Earth," an American, a Russian, and a Chinese. They all want to be the first person to set foot on Mars, and none of them liked one another.

"One fine morning three rockets took off from three different places on Earth," an American, a Russian, and a Chinese. They all want to be the first person to set foot on Mars, and none of them liked one another.

"Since all three of them were very smart, they landed on Mars at almost the same time." They get out to explore the alien landscape, but "They looked at each other distrustfully. And each kept his distance."

Then in the dead of night, afraid and alone, they each utter their word for "Mommy," which sounds almost the same in each of their languages. So they realize they're all feeling the same thing, and choose to camp together, singing songs and learning about one another.

First thing in the morning, a Martian shows up, and he's so scary looking that all three humans band together, and point their "atomic disintegrators" at him, ready to kill him. He, for his part, finds the humans to be "horrible creatures."

Then a baby bird falls from its nest, and the astronauts and the Martian all pause, and shed a tear for such a heartbreaking sight. The Martian picks up the bird and tries to shelter it, and the humans realize he's feeling the same thing they are, and they go over and shake his hands and all of them decide to return to Earth together.

"And so the visitors realized that on Earth, and on other planets, too, each one has his ways, and it's simply a matter of reaching an understanding."

WHILE THE SUBJECT IN THE THREE ASTRONAUTS feels somewhat dated, its message is not, which is why the Family Opera Initiative is currently developing an opera based on the book. A composer from each of the three countries--America, Russia, and China--is composing music, with words by American poet Nikki Giovanni. (They're looking for donations, so do click through.)

In my post on The Bomb and the General, I went into some depth raising the question, what does Eco's text say about Eco's concept of children's literature, without offering any kind of answer. It's not often that you get an answer from the artist himself, but Eugenio Carmi sat for an interview in conjunction with the opera, which provides insight into the way in which the book was created, and how he and Eco thought about children's literature.

"ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS EARTH.

"ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS EARTH."And once upon a time there was Mars."

The people of Earth want to explore Mars. They send up rockets that fall back to the ground. Then they send up rockets that go out into space. Then they send up a dog in a rocket, "but the dogs couldn't talk, and the only message they sent was 'bow wow.'" So they finally send up a man.

"One fine morning three rockets took off from three different places on Earth," an American, a Russian, and a Chinese. They all want to be the first person to set foot on Mars, and none of them liked one another.

"One fine morning three rockets took off from three different places on Earth," an American, a Russian, and a Chinese. They all want to be the first person to set foot on Mars, and none of them liked one another."Since all three of them were very smart, they landed on Mars at almost the same time." They get out to explore the alien landscape, but "They looked at each other distrustfully. And each kept his distance."

Then in the dead of night, afraid and alone, they each utter their word for "Mommy," which sounds almost the same in each of their languages. So they realize they're all feeling the same thing, and choose to camp together, singing songs and learning about one another.

First thing in the morning, a Martian shows up, and he's so scary looking that all three humans band together, and point their "atomic disintegrators" at him, ready to kill him. He, for his part, finds the humans to be "horrible creatures."

Then a baby bird falls from its nest, and the astronauts and the Martian all pause, and shed a tear for such a heartbreaking sight. The Martian picks up the bird and tries to shelter it, and the humans realize he's feeling the same thing they are, and they go over and shake his hands and all of them decide to return to Earth together.

"And so the visitors realized that on Earth, and on other planets, too, each one has his ways, and it's simply a matter of reaching an understanding."

WHILE THE SUBJECT IN THE THREE ASTRONAUTS feels somewhat dated, its message is not, which is why the Family Opera Initiative is currently developing an opera based on the book. A composer from each of the three countries--America, Russia, and China--is composing music, with words by American poet Nikki Giovanni. (They're looking for donations, so do click through.)

In my post on The Bomb and the General, I went into some depth raising the question, what does Eco's text say about Eco's concept of children's literature, without offering any kind of answer. It's not often that you get an answer from the artist himself, but Eugenio Carmi sat for an interview in conjunction with the opera, which provides insight into the way in which the book was created, and how he and Eco thought about children's literature.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu