We are all living Pasolini's Theorem

By Pepe Escobar

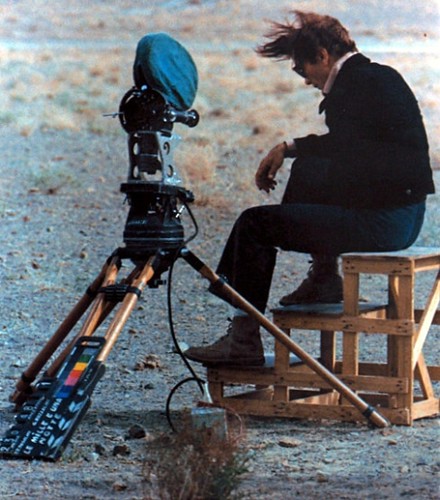

BOLOGNA - In the early morning of November 2, 1975, in Idroscalo, a terminally dreadful shanty town in Ostia, outside Rome, the body of Pier Paolo Pasolini, then 53, an intellectual powerhouse and one of the greatest filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s, was found badly beaten and run over by his own Alfa Romeo.

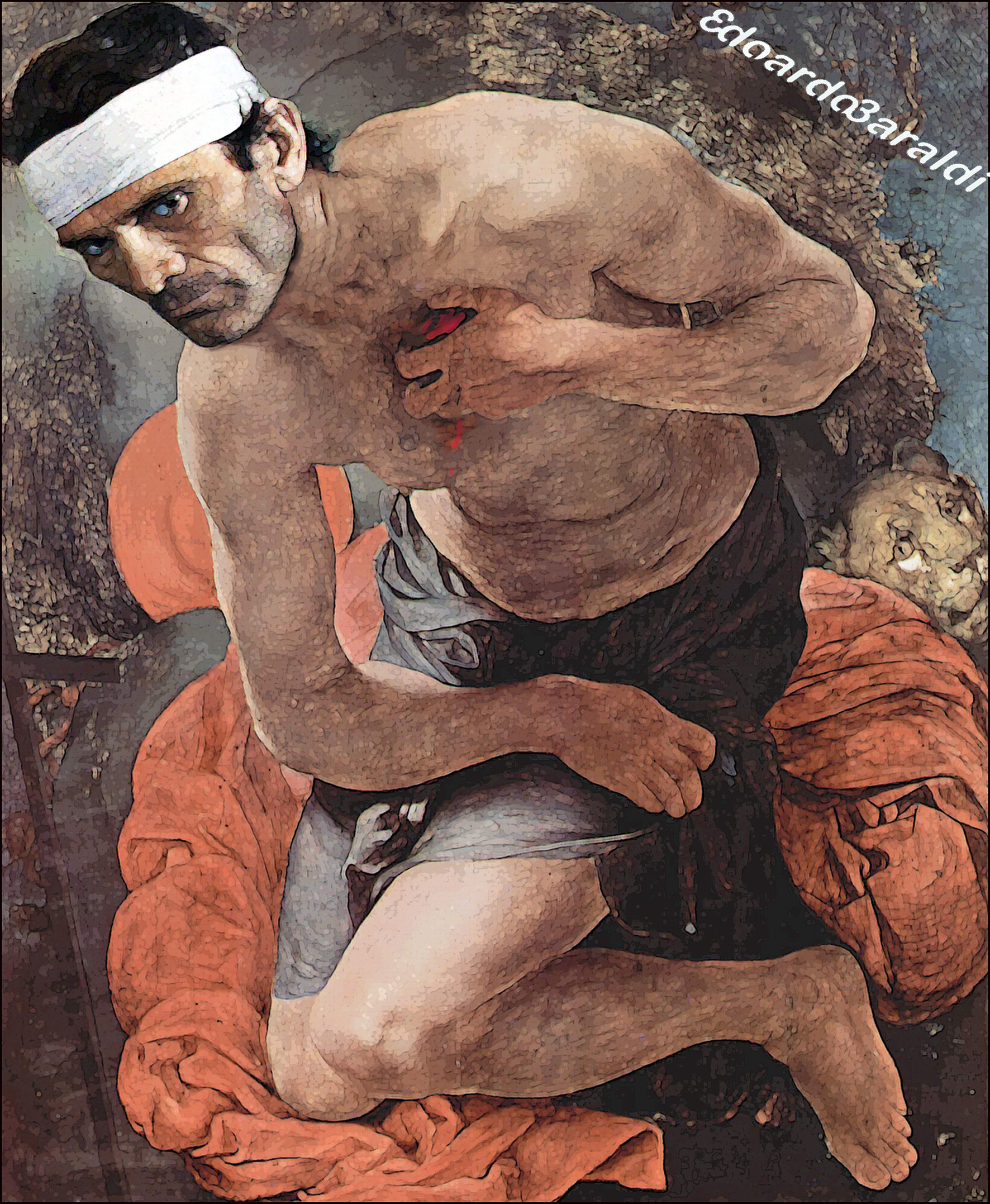

It was hard to conceive a more stunning, heartbreaking, modern mix of Greek tragedy with Renaissance iconography; in a bleak setting straight out of a Pasolini film, the author himself was immolated just like his main character in Mamma Roma (1962) lying in prison in the manner of the Dead Christ, aka theLamentation of Christ, by Andrea Mantegna.

This might have been a gay tryst gone terribly wrong; a 17-year-old low life was charged with murder, but the young man was also linked with the Italian neo-fascists. The true story has never emerged. What did emerge is that "the new Italy" - or the aftereffects of a new capitalist revolution - killed Pasolini.

'Those destined to be dead'

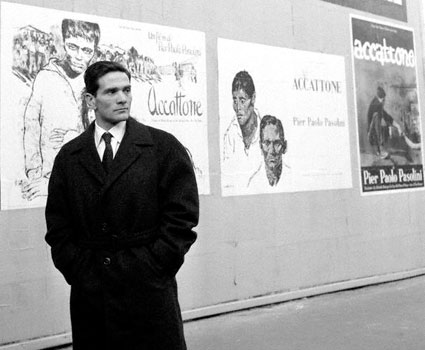

Pasolini could only reach for the stars after graduating in literature from Bologna University - the oldest in the world - in 1943. Today, a Pasolini is utterly unthinkable. He would be something like an UFIO (unidentified flying intellectual object); the total intellectual - poet, dramatist, painter, musician, fiction writer, literary theorist, filmmaker and political analyst.

For educated Italians, he was essentially a poet (what a huge compliment that meant, decades ago ...) In his masterpiece The Ashes of Gramsci (1952), Pasolini draws a striking parallel, in terms of striving for a heroic ideal, between Gramsci and Shelley - who happen to be buried in the same cemetery in Rome. Talk about poetic justice.

Then he effortlessly switched from word to image. The young Martin Scorsese was absolutely gobsmacked when he first sawAccattone (1961); not to mention the young Bernardo Bertolucci, who happened to be learning the facts on the ground as Pasolini's cameraman. At a minimum, there would be no Scorsese, Bertolucci, or for that matter Fassbinder, Abel Ferrara and countless others without Pasolini.

And especially today, as we wallow in our tawdry 24/7 Vanity Fair, it's impossible not to sympathize with Pasolini's method - which veers from sulphuric acid critique of the bourgeosie (as inTeorema and Porcile) to seeking refuge into the classics (his Greek tragedy phase) and the fascinating medieval "Trilogy of Life" - the adaptations of the Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales(1972) and Arabian Nights (1974).

It's also no wonder Pasolini decided to flee corrupt, decadent Italy and film in the developing world - from Cappadocia in Turkey forMedea to Yemen for Arabian Nights. Bertolucci later would do the same, shooting in Morocco (The Sheltering Sky), Nepal (his Buddha epic) and China (The Last Emperor, his formidable Hollywood triumph).

And then there was the unclassifiable Salo, or The 120 Days of Sodom, Pasolini's last tortured, devastating film, released only a few months after his assassination, banned for years in dozens of countries, and unforgiving in extrapolating way beyond Italy's (and Western culture's) flirt with fascism.

From 1973 to 1975, Pasolini wrote a series of columns for the Milan-based Corriere della Sera, published as Scritti Corsari in 1975 and then as Lutheran Letters, posthumously, in 1976. Their overarching theme was the "anthropological mutation" of modern Italy, which can also be read as a microcosm for most of the West.

I belong to a generation where many were absolutely transfixed by Pasolini on screen and on paper. At the time, it was clear these columns were the intellectual RPGs of an extremely sharp - but utterly alone - intellectual. Re-reading them today, they sound no less than prophetical.

When examining the dichotomy between bourgeois boys and proletarian boys - as in Northern Italy vs Southern Italy - Pasolini stumbled into no less than a new category, "difficult to describe (because no one had done it before)" and for which he had "no linguistic and terminological precedents". They were "those destined to be dead". One of them in fact, may have become his killer at Idroscalo.

As Pasolini argued, the new specimens were those who until the mid-1950s would have been victims of infant mortality. Science intervened and saved them from physical death. So they are survivors, "and in their life there's something of contro natura". Thus, Pasolini argued, as sons that are born today are not, a priori, "blessed", those that are born "in excess" are definitely "unblessed".

In short, for Pasolini, sporting a sentiment of not being really welcomed, and even being guilty about it, the new generation was "infinitely more fragile, brutish, sad, pallid, and ill than all preceding generations". They are depressed or aggressive. And "nothing may cancel the shadow that an unknown abnormality projects over their life". Nowadays, this interpretation can easily explain the alienated, cross-border Islamic youth who joins a jihad in desperation.

At the same time, according to Pasolini, this unconscious feeling of being fundamentally expendable just feeds "those destined to be dead" in their yearning for normality, "the total, unreserved adherence to the horde, the will not to look distinct or diverse". So they "show how to live conformism aggressively". They teach "renunciation", a "tendency towards unhappiness", the "rhetoric of ugliness", and brutishness. And the brutish become the champions of fashion and behavior (here Pasolini was already prefiguring punk in England in 1976).

The self-described "rationalist, idealist old bourgeois" went way beyond these reflections about the "no future for you" generation. Pasolini piled up, among other disasters, the urban destruction of Italy, the responsibility for the "anthropological degradation" of Italians, the terrible condition of hospitals, schools and public infrastructure, the savage explosion of mass culture and mass media, and the "delinquent stupidity" of television, on the "moral burden" of those who have governed Italy from 1945 to 1975, that is, the US-supported Christian Democrats.

He deftly configured the "cynicism of the new capitalist revolution - the first real rightist revolution". Such a revolution, he argued, "from an anthropological point of view - in terms of the foundation of a new 'culture' - implies men with no link to the past, living in 'imponderability'. So the only existential expectation possible is consumerism and satisfying his hedonistic impulses." This is Guy Debord's scathing 1960s "society of the spectacle" critique expanded to the dark, "dream is over" cultural horizon of the 1970s.

At the time, this was radioactive stuff. Pasolini took no prisoners; if consumerism had lifted Italy out of poverty "to gratify it with a wellbeing" and a certain non-popular culture, the humiliating result was obtained "through miming the petite bourgeoisie, stupid obligatory school and delinquent television". Pasolini used to deride the Italian bourgeoisie as "the most ignorant in all of Europe" (well, on this he was wrong; the Spanish bourgeoisie really takes the cake).

Thus arose a new mode of production of culture - built over the "genocide of precedent cultures" - as well as a new bourgeois species. If only Pasolini had survived to see it acting in full regalia, as Homo Berlusconis.

The Great Beauty is no more

Now, the consumerist heart of darkness - "the horror, the horror" - prophesized and detailed by Pasolini already in the mid-1970s has been depicted in all its glitzy tawdriness by an Italian filmmaker from Naples, Paolo Sorrentino, born when Pasolini, not to mention Fellini, were already at the peak of their powers. La Grande Bellezza ("The Great Beauty") - which has just won the Golden Globes as Best Foreign Film and will probably win an Oscar as well - would be inconceivable without Fellini's La Dolce Vita (of which it is an unacknowledged coda) and Pasolini's critique of "the new Italy".

Pasolini and Fellini, by the way, both hailed from a fabulous intellectual tradition in Emilia-Romagna (Pasolini from Bologna, Fellini from Rimini, as well as Bertolucci from Parma). In the early 1960s, Fellini used to quip with friend and still apprentice Pasolini that he was not equipped for criticism. Fellini was always pure emotion, while Pasolini - and Bertolucci - were emotion modulated by the intellect.

Sorrentino's astonishing film - a wild ride on the ramifications of Berlusconian Italy - is La Dolce Vita gone horribly sour. How not to empathize with Marcello (Mastroianni) now reaching 65 (and played by the amazing Toni Servillo), suffering from writer's block in parallel to surfing his reputation of king of Rome's nightlife. As the great Ezra Pound - who loved Italy deeply - also prophesized, a tawdry cheapness ended up outlasting our days into a Berlusconian vapidity where - according to a character - everyone "forgot about culture and art" and the former apex of civilization ended up being known only for "fashion and pizza".

This is exactly what Pasolini was telling us almost four decades ago - before an eerie, gory manifestation of this very tawdriness silenced him. His death, in the end, proved - avant la lettre - his theorem; he had always been, unfortunately, dead right.

Pepe Escobar is the author of Globalistan: How the Globalized World is Dissolving into Liquid War (Nimble Books, 2007), Red Zone Blues: a snapshot of Baghdad during the surge (Nimble Books, 2007), and Obama does Globalistan (Nimble Books, 2009).

He may be reached at pepeasia@yahoo.com.

Bologne. – Tôt le matin du 2 novembre 1975, à Idroscato, un quartier définitivement épouvantable de Ostia, dans les environs de Rome, le corps de Pier Paolo Pasolini, âgé de 53 ans, un phénomène intellectuel et l’un des plus grands cinéastes des années soixante et soixante-dix, a été trouvé, atrocement frappé et renversé par sa propre l’Alpha Romeo.

Il a été difficile de concevoir un mélange moderne plus surprenant, déchirant, de tragédie grecque avec une iconographie de la Renaissance ; dans un décors désolé, comme sorti directement d’un film de Pasolini ; l’auteur lui-même a été immolé comme son personnage principal dans Mamma Roma (1962), gisant en prison comme le Christ Mort, aussi connu comme « Les lamentation sur le Christ mort », d’Andrea Mantegna.

Il pourrait s’agir d’un rendez-vous gay ayant terriblement mal fini ; « un malfrat » de 17 ans a été accusé d’assassinat, mais le jeune homme était aussi lié aux néofascistes italiens. La véritable histoire n’a jamais été tirée au clair. Ce qui en découle est que « la nouvelle Italie » – ou les séquelles d’une nouvelle révolution capitaliste – a tué Pasolini.

« Les destinés à mourir »

Seul Pasolini a pu viser aussi haut quand après avoir été diplômé de littérature à l’Université de Bologne – la plus ancienne du monde – en 1943. Aujourd’hui, un Pasolini est tout à fait impensable. Ce serait quelque chose comme un OVINI (un objet volant intellectuel non identifié) ; l’intellectuel-poète, dramaturge, peintre, musicien, l’écrivain de fiction, théoricien littéraire, cinéaste et analyste politique total.

Pour les italiens cultivés, il a été essentiellement un poète (quel immense compliment signifiait cela, il y a des décennies …) Dans son chef-d’oeuvre « Les cendres de Gramsci », Pasolini trace un parallèle impressionnant, afin de s’efforcer à atteindre un idéal héroïque, entre Gramsci et Shelley – qui sont enterrés dans le même cimetière à Rome. Parlons de justice poétique.

Ensuite, il est passé sans aucun effort du mot à l’image. Le jeune Martin Scorsese est resté absolument abasourdi quand il a vu pour la première fois « Accattone » (1961) ; en plus du jeune Bernardo Bertolucci, qui a appris par chance le métier sur le terrain comme cadreur de Pasolini. Au minimum, il n’y aurait pas de Scorsese, de Bertolucci, ou en réalité de Fassfinder, d‘Abel Ferrara, et d’innombrables autres sans Pasolini.

Et spécialement aujourd’hui, tandis que nous nous régalons avec notre vulgaire Vanity Fair de tous les jours, il est impossible de ne pas sympathiser avec la méthode de Pasolini – qui passe de l’acide sulfurique critique de la bourgeoisie (comme dans Théorème et la Porcherie), pour chercher refuge chez les classiques (sa phase de la tragédie grecque) et la médiévale fascinante Trilogie de la Vie – les adaptations du Decamerón (1971), Les contes du Canterbury (1972), et Les Mille et une nuits (1974).

Ce n’est pas non plus surprenant que Pasolini ait décidé de fuir une Italie décadente et corrompue et de filmer le monde en développement – la Cappadoce en Turquie pour Medea, le Yémen pour Les Mille et Une nuits. Bertolucci a fait de même après, en filmant au Maroc Un thé au Sahara, au Népal (son épique Little Bouddha) et en Chine (Le dernier Empereur, son formidable triomphe à Hollywood).

Et ensuite il y a eu l’inclassable Saló ou les 120 journées de Sodome, la dernière torture, film dévastateur de Pasolini, présenté pour la première fois seulement quelques mois après son assassinat, interdit des années durant dans des douzaines de pays, et implacable dans l’extrapolation au-delà du flirt de l’Italie (et de la culture occidentale) avec le fascisme.

De 1973 à 1975, Pasolini a écrit une série d’éditos pour le Corriere della Sera, de Milan, publiés comme Écrits corsaires en 1975 et ensuite comme Lettere luterane, de manière posthume, en 1976. Son sujet prédominant était la « mutation anthropologique » de l’Italie moderne, qui peut aussi être interprétée comme un microcosme pour la plupart de l’Occident.

J’appartiens à une génération où plusieurs ont été absolument paralysés dans son étonnement par Pasolini sur l’écran et sur le papier. En ce temps-là, il était évident que ces éditos étaient les lance-grenades antichar d’un intellectuel extrêmement incisif – mais terriblement solitaire. Après les avoir récemment relus, ils n’en sont pas moins prophétiques.

Après avoir examiné la dichotomie entre jeunes bourgeois et jeunes prolétaires – comme en Italie du Nord en comparaison avec l’Italie du Sud – Pasolini a trébuché vers rien de moins qu’une nouvelle catégorie, « difficile à décrire (parce que personne ne l’avait fait avant) » et pour laquelle il n’y avait pas de « précédents linguistiques ou terminologiques ». Ils étaient « les destinés à mourir ». L’un d’eux, en fait, est peut être devenu son assassin à Idroscalo [lieu où il fut assassiné].

Comme Pasolini l’a expliqué, les nouveaux spécimens étaient qui jusqu’aux milieu des années cinquante auraient été victimes de la mortalité infantile. La science est intervenue et les a sauvés de la mort physique. Par conséquent ils sont survivants, « et dans leur vie il y a quelque chose de contre-nature ». Par conséquent, explique Pasolini, comme les enfants qui naissent actuellement ne sont pas « bénits » a priori, ceux qui naissent « en excès » sont définitivement « non bénits ».

Bref, pour Pasolini, la nouvelle génération en se targuant d’un sentiment de ne pas être réellement bienvenus, et même de se sentir coupables à ce sujet, était infiniment « plus fragile, ignorante, triste, hâve et malade que toutes les générations précédentes ». Ils sont déprimés ou agressifs. Et « rien ne peut éliminer l’ombre qu’une anomalie inconnue a projetée sur leur vie ». Actuellement, cette interprétation peut facilement expliquer, l’aliénée, transnationale, jeunesse islamique qui se joint à un djihad par désespoir.

En même temps, selon Pasolini, ce sentiment inconscient d’être fondamentalement jetables, touche seulement « les destinés à mourir » dans leur souhait de normalité, « l’adhésion totale, sans réserves, à la horde, la volonté de ne pas sembler différents ou distincts ». Par conséquent « ils montrent comment vivre agressivement le conformisme ». Ils apprennent le « renoncement », « une tendance vers le malheur », la « rhétorique de la laideur », et l’ignorance. Et les ignorants se convertissent en champions de la mode et du comportement (ici Pasolini prédisait déjà les punks en Angleterre en 1976).

Le « vieux bourgeois idéaliste, rationaliste » tel qu’il s’auto-décrit, a été beaucoup plus loin que ces réflexions sur la génération « sans avenir ». Pasolini a ajouté, entre autres catastrophes, la destruction urbaine de l’Italie, la responsabilité de la « dégradation anthropologique des italiens, la terrible condition des hôpitaux, écoles et de l’infrastructure publique, l’explosion sauvage de la culture et des médias de masses, et la « stupidité délinquante » de la télévision, du « poids moral » de ceux qui ont gouverné l’Italie de 1945 à 1975, c’est-à-dire, les démocrates-chrétiens appuyés par les Etats-Unis d’Amérique.

Il a habilement cerné « le cynisme de la nouvelle révolution capitaliste – de la première vraie révolution de droite ». Une révolution semblable, a-t-il expliqué, « d’un point de vue anthropologique – en termes de fondation d’une nouvelle ‘culture’ – implique des hommes sans aucun lien avec le passé, qui vivent dans l’impondérabilité’. Par conséquent l’unique expectative existentielle possible est la consommation et la satisfaction de ses impulsions hédonistes ». C’est la critique mordante de la « société du spectacle » de Guy Debord dans les années soixante étendue à l’obscur horizon culturel du « le rêve est fini » des années soixante-dix.

A cette époque, c’était du matériel radioactif. Pasolini n’avait pas de contemplations ; si la consommation avait sorti l’Italie de la pauvreté « pour la satisfaire par du bien-être » et une certaine culture non populaire, le résultat humiliant a été atteint « en flattant la petite bourgeoisie, la stupide école obligatoire et la télévision délinquante ». Pasolini avait l’habitude de ridiculiser la bourgeoisie italienne comme la « plus ignorante de toute l’Europe » (bon, en cela il se trompait ; la bourgeoisie espagnole remporte réellement la palme d’or).

Ainsi un nouveau mode de production de culture – construite sur le « génocide des cultures précédentes » est apparu – ainsi qu’une nouvelle espèce bourgeoise. Si seulement Pasolini avait survécu pour la voir en jouant le rôle d’honneur, comme Homo Berlusconis.

La Grande Beauté n’existe plus

Maintenant, le cœur des ténèbres consommatrices – « l’horreur, l’horreur » – déjà prophétisée et détaillée par Pasolini vers le milieu des années soixante-dix, et dont un cinéaste italien de Naples Paolo Sorrentino, né quand Pasolini, pour ne pas mentionner Fellini, était déjà au sommet de son pouvoir, a fait le portrait dans toute son ostentation éblouissante. La grande bellezza (2013)– qui vient d’obtenir le Golden Globe comme Meilleur Film Étranger et qui probablement gagnera un Oscar aussi – serait inconcevable sans La Dolce Vita (dont c’est un coda [1] non reconnue) et sans la critique de « la nouvelle Italie » de Pasolini.

À propos, Pasolini et Fellini étaient issus tous deux d’une fabuleuse tradition intellectuelle de l’Emilie-Romagne (Pasolini de Bologne, Fellini de Rimini, ainsi que Bertolucci de Parme). Au début des années soixante, Fellini avait l’habitude de dire en plaisantant avec son ami, et encore apprenti, Pasolini qu’il n’était pas armé pour la critique. Fellini a toujours été pure émotion, tandis que Pasolini – et Bertolucci – étaient l’émotion modulée par l’intellect.

Le surprenant film de Sorrentino – une promenade sauvage dans les ramifications de l’Italie berlusconienne – est La Dolce Vita horriblement amère. Comment ne pas s’identifier à Marcello (Mastroianni) qui arrive maintenant à 65 ans (et interprété par le surprenant Toni Servillo), souffrant d’un syndrome de la page blanche tout en surfant sur sa réputation de roi de la vie nocturne de Rome. Comme le grand Ezra Pound – qui aimait profondément l’Italie – le prédit aussi, une babiole de mauvais goût qui finit par survivre jusqu’à nos jours dans une futilité berlusconienne où – selon un personnage – tous « ont oublié la culture et l’art » et l’ancien apex de la civilisation a fini par se réduire à « la mode et la pizza ».

C’est exactement ce que Pasolini nous disait il y a presque quarante ans– avant qu’une manifestation spectrale, ensanglantée de cette même ostentation ne l’étouffât. Enfin, sa mort a prouvé –avant la lettre– son théorème ; il a toujours eu, malheureusement, vraiment raison.

Pepe Escobar

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu