Among the Immortals

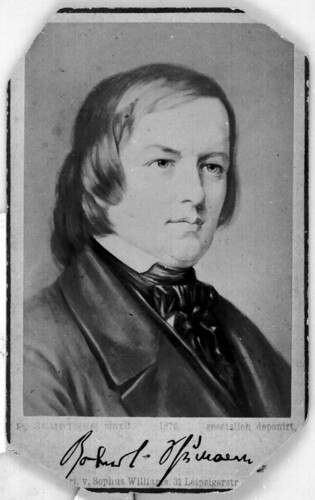

Does Schumann belong there?

George B. Stauffer

Living in a century of unbalanced geniuses—Poe, Nietzsche, Maupassant, van Gogh—Schumann ranks as one of the most complex. Airing his bipolar nature publicly in the form of the fictional figures Florestan, the extroverted idealist, and Eusebius, the introverted dreamer, and writing music heavily coded with people and events, Schumann lived his art to such a degree that his anxious personal life and his mercurial compositions became one and the same. Bravely balancing domestic tranquility with inner torment, he wrote works that have become staples of the Western repertoire. At the same time, he composed pieces that continue to produce universal head-scratching. Schumann fought for the cause of good music, but what was truly at stake, it seems, was his own sanity: He eventually threw himself into the Rhine in a failed suicide attempt and ended up in a straitjacket in an asylum. Here is a figure troubled enough for the 21st century!

Schumann’s life and work receive close scrutiny in this new biography by a senior German music scholar and author of more than a dozen books, including a widely admired study of Bach. Presented here in a deft, finely nuanced translation, Martin Geck’s volume first appeared in German three years ago as part of the bicentennial celebration of Schumann’s birth. The timing was propitious, for a host of new documents and insights made a reappraisal of Schumann’s complicated career most appropriate.

Geck takes the unusual approach of supplementing the 12 chapters of his book with 9 short intermezzi. The chapters cover the obligatory biographical bases and take the reader through Schumann’s life phase-by-phase. In the intermezzi, Geck pauses to explore special aspects of the composer and his work, such as the influence of Jean Paul’s Flegeljahre (The Awkward Age, from which Schumann claimed to have learned more counterpoint than anywhere else); Genoveva (Schumann’s well-intentioned but ill-fated opera); and the magic of allusions, or narrative elements, in Schumann’s music. The succinct, whimsical intermezzi are not unlike the flittering digressions in Schumann’s works, where forward motion is commonly interrupted by episodic detours. In addition, Geck analyzes Schumann’s music more by metaphor than by traditional theory. This allows him to address individual pieces on their own psychological terms.

Schumann was born in 1810 in Zwickau, a small town some 50 miles south of Leipzig. His father published and sold books, and Schumann demonstrated both literary and musical gifts at an early age. From adolescence onward, he consciously strove to become an “artist of genius,” writing his first curriculum vitae at age 14 and starting the lifelong habit of documenting the intimate details of his day-to-day activities through journals, travel logs, housekeeping books, marriage diaries, and hundreds of letters. (As an adult, Schumann even noted intercourse on his personal calendar.)

In high school, he formed a literary society with his school chums that fostered heady discussions of E. T. A. Hoffmann, Ludwig Tieck, Jean Paul, and other Romantic writers. As Geck points out, the young Schumann was deeply impressed by Flegeljahre’s contrasting twins Vult and Walt, who would become models for his own soon-to-be-born characters. It is hard to imagine Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven indulging in such literary fantasies. The suicide of Schumann’s older sister Emilie in 1825 foreshadowed dark things to come.

Following the death of his father, in 1826, Schumann enrolled at the university in Leipzig. Pushed by his mother to pursue law, he focused instead on literature. In his spare time, he drank and smoked with his fellow students and studied piano with the well-known pedagogue Friedrich Wieck, whose 12-year-old daughter Clara, a budding piano prodigy, would later become Schumann’s wife. In his 20th year, Schumann presented a magnificent piano recital, but shortly thereafter wrote in his diary of finger problems, which soon became full-blown paralysis. Splints, alcohol baths, and herbal treatments provided no relief, and for the rest of his life Schumann avoided the use of the index finger in his right hand when playing the piano. This precluded the life of a virtuoso, leaving writing and composing as his best alternatives.

Two years later, Schumann experienced his first serious bouts of “melancholia.” He chose to fight off depression by immersing himself in work, in this case launching a semiweekly music journal, Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), filled with reviews, essays, chronicles, and reports from correspondents. This allowed him to create his own imaginary world, reporting the latest developments in music through the characters of Florestan, Eusebius, Master Raro (a thinly veiled portrait of Friedrich Wieck), and Zilia-Chiara-Chiarina (a composite portrait of Clara Wieck) from the “League of David”—a fictional band of solders engaged in battle with musical philistines.

The Neue Zeitschrift was a remarkable undertaking for a 23-year-old, and for the next 12 years Schumann ran it mostly as a one-man show, singlehandedly ushering in a “new poetic age” through the imaginative magic of his pen. As Geck nicely expresses it, Schumann succeeded by fusing reality and fiction, poetry and politics, public and private reports, artistic ideals and self-promotion. He wrote more than 2,500 letters to correspondents and fielded more than 5,500 in return. The Neue Zeitschrift became the musical forum for tracking the development of German Romanticism. Its passionate, highly personal accounts still make for lively reading today.

At the same time, Schumann began to publish the piano pieces that made him famous, suites of vividly painted character pieces that appeared in steady succession after 1831: the Abegg Variations, Papillons, Faschingsschwank aus Wien (“Carnival Prank from Vienna”), Carnaval, Kinderscenen (“Scenes from Childhood”), and Kreisleriana (Hoffmann’s tales of the mad Kapellmeister Kreisler). Written in a narrative style, the works dwell on memories and thoughts without following traditional models. Masquerade balls, carnival pranks, and youthful memories fly by in whimsical processions. When listening to the pieces, one has the impression of Schumann improvising on the piano in his parlor, brandy and cigar in hand. As he wrote in his diary: “Notes in themselves cannot really paint what the emotions have not already portrayed.”

In 1837, Schumann became engaged to Clara Wieck, now 17, but was denied her hand by her father, who feared his talented daughter would have to sacrifice her performing career. For three years, Schumann and Clara carried out a clandestine relationship, meeting secretly and exchanging letters through intermediaries. This was followed by a humiliating lawsuit, in which Schumann’s friends were summoned to testify to his moral rectitude and financial stability. In the end, the court ruled in Schumann’s favor, and the couple was married in 1840. Schumann was 30; Clara was 20.

The long-desired union led to Schumann’s famous “Year of Song,” as he himself later put it. Liederkreis (“Song Cycle”), Dichterliebe (“Loves of a Poet”), Frauenliebe und -leben (“A Woman’s Love and Life”), and many other compositions flowed from his pen in quick succession, a musical reflection of his rhapsodic love for Clara, but also a practical means of providing financial support for his future family. (Marie, the first of seven children, was born a year later.)

The songs may be Schumann’s richest contribution to the Romantic repertory. Geck shows how they eclipse even the magnificent lieder of Schubert by fully incorporating the piano in the storytelling and creating a new synthesis of music and poetry. Schumann replaced rote structures with more inventive schemes intended to bring out and heighten the emotional content of the verse. In Schumann’s songs, the piano becomes a true partner with the voice, introducing and developing themes with equal conviction. “Er, der Herrlichste von allen” (“He, the most glorious of all”), from Frauenliebe und -leben, is among the purest expressions of Romantic adulation in the 19th century.

In Leipzig, Schumann found a kindred spirit in Felix Mendelssohn, who had arrived in 1835 to take up the directorship of the Gewandhaus Orchestra. The two soon joined forces to promote new music and old, the latter represented especially by the works of Bach, which were championed in a series of historical concerts presented by Mendelssohn and reviewed by Schumann in the Neue Zeitschrift. The first Bach monument in Leipzig was erected in 1843, the result of Mendelssohn’s benefit concerts and Schumann’s promotional efforts. (It can be viewed today in the small park behind the St. Thomas Church.) The Schumann-Mendelssohn friendship also brought together two of Europe’s first musical power couples: Schumann and Clara, and Mendelssohn and his brilliantly talented sister Fanny (“a lively, fiery Jewess,” Schumann wrote in his diary). In addition to being piano virtuosos, the women were gifted composers, Clara writing songs that rivaled those of her husband and Fanny writing songs without words that rivaled those of her brother.

After the Year of Song, Schumann turned to instrumental works, with mixed results. His symphonies lacked the force and focus of Beethoven’s, and his chamber works seemed too formal. Impatient with Leipzig audiences and tired of the Neue Zeitschrift (he gave up the editorship in 1844), Schumann moved with his growing family to Dresden, where he fought escalating emotional problems by writing a series of contrapuntal piano works. In Dresden, Wagner held sway, however, and Schumann’s great effort at opera, Genoveva, which premiered in Leipzig in 1850, was no match for Lohengrin, which premiered in Dresden two months later.

In Genoveva, Schumann explored the inner lives of his characters in great detail, but he failed to create a plot that moves the drama forward. As Geck points out, by midcentury, German audiences wanted something to unite and motivate das Volk rather than provide dark, brooding introspection. Like Schumann’s earlier dramatic vocal work, Das Paradies und die Peri (“Paradise and the Peri”), Genoveva remains more discussed than produced.

Dresden offered less opportunity than expected, and soon after the lukewarm response to Genoveva, Schumann accepted the post of municipal music director in Düsseldorf. This new position provided a steady paycheck, but Schumann was not enthusiastic about the work, which required him to lead a choral society and municipal orchestra composed mostly of amateurs. Unlike Mendelssohn, Schumann was neither a skilled conductor nor a strong motivator, and, in time, as frictions increased, he was asked to conduct only his own works. Schumann nevertheless continued to produce a steady flow of compositions: choral works, violin sonatas, violin and cello concertos, and a host of pieces that have never been fully embraced.

Clara continued to present well-attended piano concerts that she played from memory (she was one of the first to accomplish this feat), and in 1853, the young Johannes Brahms entered their lives, prompting Schumann to write his “New Paths” essay for the Neue Zeitschrift, hailing the conservative young composer with the famous phrase, “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius.”

Schumann’s psychological disorders became still more acute, and by early 1854, he had difficulty speaking and hearing. Clara reported in her diary that her husband was haunted by the singing of angels that soon turned into “demonic voices attended by terrible music,” declaring that he was “a sinner whom they planned to cast down into Hell.” After attempting suicide, Schumann requested removal to an asylum in Endenich, where he died two years later at 46, a victim of extreme melancholia and delusions.

Did he die from the long-term effects of syphilis, as often proposed? Geck thinks not—and suggests, instead, a hereditary affliction: Schumann’s son Ludwig was mentally deranged, and his son Ferdinand became dependent on drugs. Supportive to the end, Clara lived another 40 years, promoting and publishing her late husband’s works. She remained a close friend to Brahms, but no more than that, Geck believes.

Schumann’s life played out on the musical battleground occupied by conservative and progressive camps. The conservative composers backed “absolute” music—that is, instrumental music that could stand on its own, without words or programs. Meaning was derived solely from the exposition and development of themes within clearly defined structures—“forms animated by musical sounds,” as the Viennese champion of absolute music Eduard Hanslick described it.

The progressive composers—the “New German School”—advocated a more expressive, encompassing approach. Passions, moods, ethical attitudes, and even political stances were conveyed by extra-musical means (texts, programs, scenery, lighting) in amorphous structures shaped by the emotion of the moment. Brahms emerged as the standard-bearer of the conservatives; Liszt and Wagner led the New German School.

Ironically, both camps looked to Beethoven as their founder. His First, Second, Fourth, Seventh, and Eighth Symphonies, with their clear-cut formal plans, served as the model for conservatives. His Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Ninth, with their programmatic slants (the life of Napoleon, fate knocking at the door, country scenes, universal brotherhood), set the precedent for the progressives. Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Schumann sought a middle ground. Schubert pursued a lyrical solution to the symphony, filling his works with gorgeous melodies that kept the structures afloat. Mendelssohn relied on a more formal approach, even turning to Bach-inspired chorales to hold his symphonies together.

Like Liszt and Wagner, Schumann believed in the tone poem. But whereas Liszt and Wagner anchored their works in Teutonic myth, using music as a means to an end, Schumann grounded his pieces in everyday life, using inspiration as a means to music. Whether or not the quotidian translates into a compelling listening experience remains unclear, as Geck admits.

Indeed, the question that Geck does not squarely face is whether or not Schumann was essentially a miniaturist, like Chopin or Satie. In the early piano cycles and lieder from the Year of Song, Schumann was able to create small scenes filled with great emotion and vitality. In the larger works, however, he seemed either to yield to episodic disintegration (as in the Violin Concerto) or to succumb to formulaic repetition (the Piano Quintet in E-flat Major). Only in the A-minor Piano Concerto, the Rhenish Symphony, and a few other magnificent compositions does he attain the perfect balance of fantasy and unity. It fell to Brahms and Wagner to find fruitful solutions, both radical and conservative, to sustain massive musical structures over large stretches of time.

Robert Schumann is a welcome update on the life and work of the first fully Romantic composer. By taking a narrative approach and relying heavily on commentaries from the time, Martin Geck is able to weigh Schumann and his music fairly and appropriately. The topical approach occasionally produces lapses: Children are mentioned before their births have been noted; the Schumanns are suddenly living in Dresden (in intermezzo VI) before they have departed from Leipzig (in chapter nine); Schumann’s stay in Endenich is cited before its context has been explained. But these are peccadilloes in an otherwise masterfully written account that shows just how lively and controversial the works and writings of this remarkable musician-poet remain, even at a distance of two centuries.

George B. Stauffer is dean of the Mason Gross School of the Arts and professor of music history at Rutgers.

Traducere // Translate

What are we to make of Robert Schumann?

Abonați-vă la:

Postare comentarii (Atom)

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu