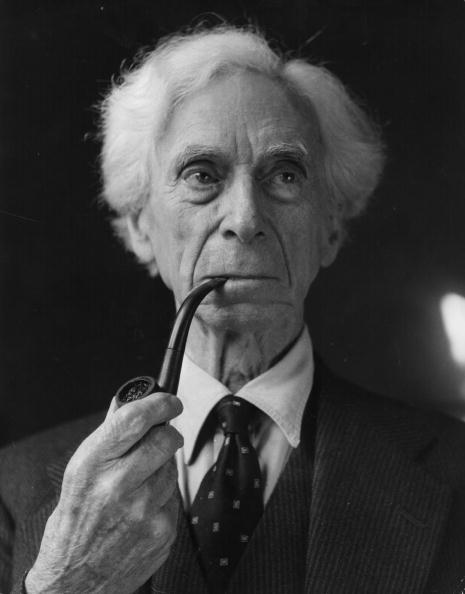

Hey maggie johnson! An earlier version of this email contained broken links – the trouble with being human, my apologies. Here is the exact same thing, with all the links working. Happy Sunday! Hey maggie johnson! An earlier version of this email contained broken links – the trouble with being human, my apologies. Here is the exact same thing, with all the links working. Happy Sunday! On the art of acquiring "a high degree of intellectual culture without emotional atrophy." One of Russell's key assertions is that science education – something that leaves much to be desired nearly a century later – is key to attaining a future of happiness and democracy:  For the first time in history, it is now possible, owing to the industrial revolution and its byproducts, to create a world where everybody shall have a reasonable chance of happiness. Physical evil can, if we choose, be reduced to very small proportions. It would be possible, by organization and science, to feed and house the whole population of the world, not luxuriously, but sufficiently to prevent great suffering. It would be possible to combat disease, and to make chronic ill-health very rare. … All this is of such immeasurable value to human life that we dare not oppress the sort of education which will tend to bring it about. in such an education, applied science will have to be the chief ingredient. Without physics and physiology and psychology, we cannot build the new world. For the first time in history, it is now possible, owing to the industrial revolution and its byproducts, to create a world where everybody shall have a reasonable chance of happiness. Physical evil can, if we choose, be reduced to very small proportions. It would be possible, by organization and science, to feed and house the whole population of the world, not luxuriously, but sufficiently to prevent great suffering. It would be possible to combat disease, and to make chronic ill-health very rare. … All this is of such immeasurable value to human life that we dare not oppress the sort of education which will tend to bring it about. in such an education, applied science will have to be the chief ingredient. Without physics and physiology and psychology, we cannot build the new world. Still, Russell is sure to offer a disclaimer, advocating for the equal importance of the humanities, and asks:  What will be the good of the conquest of leisure and health, if no one remembers how to use them? What will be the good of the conquest of leisure and health, if no one remembers how to use them?  It is only through imagination that men become aware of what the world might be; without it, 'progress' would become mechanical and trivial. It is only through imagination that men become aware of what the world might be; without it, 'progress' would become mechanical and trivial.[…] Cast-iron rules are above all things to be avoided. In a mechanistic civilization, there is grave danger of a crude utilitarianism, which sacrifices the whole aesthetic side of life to what is called 'efficiency.'   Passionate beliefs produce either progress or disaster, not stability. Science, even when it attacks traditional beliefs, has beliefs of its own, and can scarcely flourish in an atmosphere of literary skepticism. … And without science, democracy is impossible. Passionate beliefs produce either progress or disaster, not stability. Science, even when it attacks traditional beliefs, has beliefs of its own, and can scarcely flourish in an atmosphere of literary skepticism. … And without science, democracy is impossible.[…] Neither acquiescence in skepticism nor acquiescence in dogma is what education should produce. What it should produce is a belief that knowledge is attainable in a measure, though with difficulty; that much of what passes for knowledge at any given time is likely to be more or less mistaken, but that the mistakes can be rectified by care and industry. In acting upon our beliefs, we should be very cautious where a small error would mean disaster; nevertheless it is upon our beliefs that we must act. This state of mind is rather difficult: it requires a high degree of intellectual culture without emotional atrophy. But though difficult it is not impossible; it is in fact the scientific temper. Knowledge, like other good things, is difficult, but not impossible; the dogmatist forgets the difficulty, the skeptic denies the possibility. Both are mistaken, and their errors, when wide-spread, produce social disaster. In a later chapter, he considers another double-edged sword of dogmatic thinking:  It is a dangerous error to confound truth with matter-of-fact. Our life is governed not only by facts, but by hopes; the kind of truthfulness which sees nothing but facts is a prison for the human spirit. It is a dangerous error to confound truth with matter-of-fact. Our life is governed not only by facts, but by hopes; the kind of truthfulness which sees nothing but facts is a prison for the human spirit.  In the immense majority of children, there is the raw material of a good citizen and also the raw material of a criminal. In the immense majority of children, there is the raw material of a good citizen and also the raw material of a criminal.[…] The raw material of instinct is ethically neutral, and can be shaped either to good or evil by the influence of the environment. Artwork: "Choosing Sides" by Owen Mortensen, courtesy my living room wall In a related meditation, Russell articulates beautifully something ineffable yet essential, something we too frequently forget, of which a dear friend recently reminded me, and writes:  Construction and destruction alike satisfy the will to power, but construction is more difficult as a rule, and therefore gives more satisfaction to the person who can achieve it. … We construct when we increase the potential energy of the system in which we are interested, and we destroy when we diminish the potential energy. ... Whatever may be thought of these definitions, we all know in practice whether an activity is to be regarded as constructive or destructive, except in a few cases where a man professes to be destroying with a view to rebuilding and are not sure whether he is sincere. Construction and destruction alike satisfy the will to power, but construction is more difficult as a rule, and therefore gives more satisfaction to the person who can achieve it. … We construct when we increase the potential energy of the system in which we are interested, and we destroy when we diminish the potential energy. ... Whatever may be thought of these definitions, we all know in practice whether an activity is to be regarded as constructive or destructive, except in a few cases where a man professes to be destroying with a view to rebuilding and are not sure whether he is sincere. […] The first beginnings of many virtues arise out of experiencing the joys of construction. […] Those whose intelligence is adequate should be encouraged in using their imaginations to think out more productive ways of utilizing existing social forces or creating new ones. "Where the myth fails, human love begins. Then we love a human being, not our dream, but a human being with flaws." "Show up, show up, show up, and after a while the muse shows up, too."   I need to tell a story. It's an obsession. Each story is a seed inside of me that starts to grow and grow, like a tumor, and I have to deal with it sooner or later. Why a particular story? I don't know when I begin. That I learn much later. Over the years I've discovered that all the stories I've told, all the stories I will ever tell, are connected to me in some way. If I'm talking about a woman in Victorian times who leaves the safety of her home and comes to the Gold Rush in California, I'm really talking about feminism, about liberation, about the process I've gone through in my own life, escaping from a Chilean, Catholic, patriarchal, conservative, Victorian family and going out into the world. I need to tell a story. It's an obsession. Each story is a seed inside of me that starts to grow and grow, like a tumor, and I have to deal with it sooner or later. Why a particular story? I don't know when I begin. That I learn much later. Over the years I've discovered that all the stories I've told, all the stories I will ever tell, are connected to me in some way. If I'm talking about a woman in Victorian times who leaves the safety of her home and comes to the Gold Rush in California, I'm really talking about feminism, about liberation, about the process I've gone through in my own life, escaping from a Chilean, Catholic, patriarchal, conservative, Victorian family and going out into the world.  It's so important for me, finding the precise word that will create a feeling or describe a situation. I'm very picky about that because it's the only material we have: words. But they are free. No matter how many syllables they have: free! You can use as many as you want, forever. It's so important for me, finding the precise word that will create a feeling or describe a situation. I'm very picky about that because it's the only material we have: words. But they are free. No matter how many syllables they have: free! You can use as many as you want, forever. In fact, her style is deeply reminiscent of beloved French-Cuban writer Anaïs Nin's – and Allende herself offers a beautiful hypothesis about a common thread:  I try to write beautifully, but accessibly. In the romance languages, Spanish, French, Italian, there's a flowery way of saying things that does not exist in English. My husband says he can always tell when he gets a letter in Spanish: the envelope is heavy. In English a letter is a paragraph. You go straight to the point. In Spanish that's impolite. Reading in English, living in English, has taught me to make language as beautiful as possible, but precise. Excessive adjectives, excessive description – skip it, it's unnecessary. Speaking English has made my writing less cluttered. I try to read House of the Spirits now, and I can't. Oh my God, so many adjectives! Why? Just use one good noun instead of three adjectives. I try to write beautifully, but accessibly. In the romance languages, Spanish, French, Italian, there's a flowery way of saying things that does not exist in English. My husband says he can always tell when he gets a letter in Spanish: the envelope is heavy. In English a letter is a paragraph. You go straight to the point. In Spanish that's impolite. Reading in English, living in English, has taught me to make language as beautiful as possible, but precise. Excessive adjectives, excessive description – skip it, it's unnecessary. Speaking English has made my writing less cluttered. I try to read House of the Spirits now, and I can't. Oh my God, so many adjectives! Why? Just use one good noun instead of three adjectives.  Fiction happens in the womb. It doesn't get processed in the mind until you do the editing. Fiction happens in the womb. It doesn't get processed in the mind until you do the editing.  I start all my books on January eighth. Can you imagine January seventh? It's hell. Every year on January seventh, I prepare my physical space. I clean up everything from my other books. I just leave my dictionaries, and my first editions, and the research materials for the new one. And then on January eighth I walk seventeen steps from the kitchen to the little pool house that is my office. It's like a journey to another world. It's winter, it's raining usually. I go with my umbrella and the dog following me. From those seventeen steps on, I am in another world and I am another person. I go there scared. And excited. And disappointed – because I have a sort of idea that isn't really an idea. The first two, three, four weeks are wasted. I just show up in front of the computer. Show up, show up, show up, and after a while the muse shows up, too. If she doesn't show up invited, eventually she just shows up. I start all my books on January eighth. Can you imagine January seventh? It's hell. Every year on January seventh, I prepare my physical space. I clean up everything from my other books. I just leave my dictionaries, and my first editions, and the research materials for the new one. And then on January eighth I walk seventeen steps from the kitchen to the little pool house that is my office. It's like a journey to another world. It's winter, it's raining usually. I go with my umbrella and the dog following me. From those seventeen steps on, I am in another world and I am another person. I go there scared. And excited. And disappointed – because I have a sort of idea that isn't really an idea. The first two, three, four weeks are wasted. I just show up in front of the computer. Show up, show up, show up, and after a while the muse shows up, too. If she doesn't show up invited, eventually she just shows up. Like Neil Gaiman, who famously advised to "keep moving" because "perfection is like chasing the horizon," Allende shares a cautionary observation:  I correct to the point of exhaustion, and then finally I say I give up. It's never quite finished, and I suppose it could always be better, but I do the best I can. In time, I've learned to avoid overcorrecting. When I got my first computer and I realized how easy it was to change things ad infinitum, my style became very stiff. I correct to the point of exhaustion, and then finally I say I give up. It's never quite finished, and I suppose it could always be better, but I do the best I can. In time, I've learned to avoid overcorrecting. When I got my first computer and I realized how easy it was to change things ad infinitum, my style became very stiff. But her most profound test of creative resilience came from deeply untethering personal tragedy:  My daughter, Paula, died on December 6, 1992. On January 7, 1993, my mother said, 'Tomorrow is January eighth. If you don't write, you're going to die.' She gave me the 180 letters I'd written to her while Paula was in a coma, and then she went to Macy's. When my mother came back six hours later, I was in a pool of tears, but I'd written the first pages of Paula. Writing is always giving some sort of order to the chaos of life. It organizes life and memory. To this day, the responses of the readers help me to feel my daughter alive. My daughter, Paula, died on December 6, 1992. On January 7, 1993, my mother said, 'Tomorrow is January eighth. If you don't write, you're going to die.' She gave me the 180 letters I'd written to her while Paula was in a coma, and then she went to Macy's. When my mother came back six hours later, I was in a pool of tears, but I'd written the first pages of Paula. Writing is always giving some sort of order to the chaos of life. It organizes life and memory. To this day, the responses of the readers help me to feel my daughter alive. Turning an eye towards the future of storytelling, Allende advocates for medium-agnosticism, reminding us that a great story will always be a great story, wherever it lives – so long as it lives in the heart:  Storytelling and literature will exist always, but what shape will it take? Will we write novels to be performed? The story will exist, but how, I don't know. The way my stories are told today is by being published in the form of a book. In the future, if that's not the way to tell a story, I'll adapt. Storytelling and literature will exist always, but what shape will it take? Will we write novels to be performed? The story will exist, but how, I don't know. The way my stories are told today is by being published in the form of a book. In the future, if that's not the way to tell a story, I'll adapt. She ends with three pieces of advice for aspiring writers:  It's worth the work to find the precise word that will create a feeling or describe a situation. Use a thesaurus, use your imagination, scratch your head until it comes to you, but find the right word. It's worth the work to find the precise word that will create a feeling or describe a situation. Use a thesaurus, use your imagination, scratch your head until it comes to you, but find the right word.- When you feel the story is beginning to pick up rhythm—the characters are shaping up, you can see them, you can hear their voices, and they do things that you haven't planned, things you couldn't have imagined—then you know the book is somewhere, and you just have to find it, and bring it, word by word, into this world.

- When you tell a story in the kitchen to a friend, it's full of mistakes and repetitions. It's good to avoid that in literature, but still, a story should feel like a conversation. It's not a lecture.

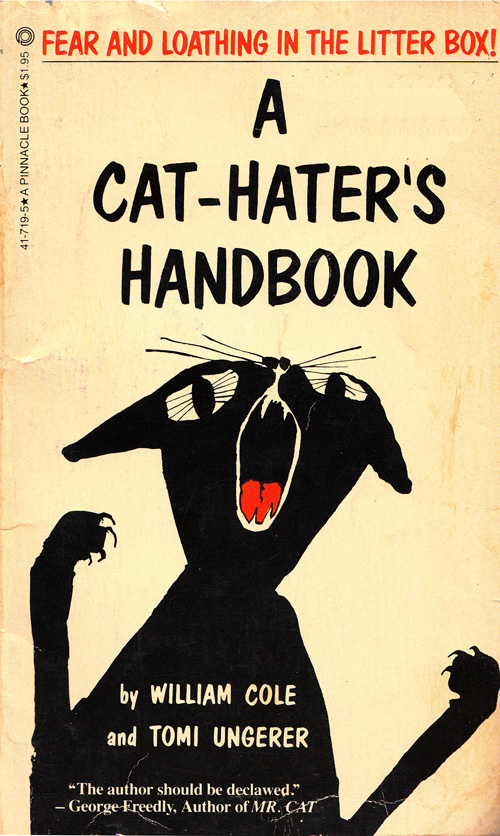

Allende's moving 2007 TED talk will give you an even deeper appreciation for her singular approach to storytelling. The rest of Why We Write features insights and advice on the craft from such contemporary icons as Jennifer Egan, Michael Lewis, Susan Orlean, and James Frey, among others. Pair it with H. P. Lovecraft's advice to aspiring writers, F. Scott Fitzgerald's letter to his daughter, Zadie Smith's 10 rules of writing, Kurt Vonnegut's 8 keys to the power of the written word, David Ogilvy's 10 no-bullshit tips, Henry Miller's 11 commandments, Jack Kerouac's 30 beliefs and techniques, John Steinbeck's 6 pointers, Neil Gaiman's 8 rules, Margaret Atwood's 10 practical tips, and Susan Sontag's synthesized learnings. What Aldous Huxley's misogynism has to do with children's books, darkness, and modern love. In a recent episode of her fantastic Design Matters show, Debbie Millman talks to Blackall about the difference between an artist and an illustrator, what makes children's storytelling particularly exciting, the origin and afterlife of the missed connections project, and more. The interview is excellent in its entirety, but here are some favorite excerpts:  SB: I think children are pretty subversive creatures. SB: I think children are pretty subversive creatures.DM: It's interesting: It's subversive in the way that The Wizard of Oz is subversive – there's a subtext. And that subtext has to do with love, and longing, and loss, and pain. But I guess, for me, there seems to be an innate optimism that doesn't feel dark – yes, there's darkness in the work, but I always get the sense that the light overcomes that darkness. … You can create a brush stroke that somehow defines wistfulness. But in that ability to see that wistfulness, I can't help but feel understood – which … then gives me a great sense of joy.  The [missed connections] listings were intriguing because they mixed the natural desire to make a first impression and the very human need to get a second chance. The [missed connections] listings were intriguing because they mixed the natural desire to make a first impression and the very human need to get a second chance. But the most tender, moving, and poetic of the stories will stop your breath:   The Whale at Coney Island The Whale at Coney Island – M4M – 69 (Brooklyn/Florida) A young friend of mine recently acquainted me with the intricacies of Missed Connections, and I have decided to try to find you one final time. Many years ago, we were friends and teachers together in New York City. Perhaps we could have been lovers too, but we were not. We used to take trips to Coney Island, especially during the spring, when we would stroll hand in hand, until our palms got too sweaty, along the boardwalk, and take refuge in the cool darkness of the aquarium. We liked to visit the whale best. One spring, it arrived from its winter home (in Florida? I can't remember) pregnant. Everyone at the aquarium was very excited – a baby beluga whale was going to be born in New York City! You insisted that we not miss the birth, so every day after class, and on both Saturday and Sunday, we would take the D train all the way from Harlem to Coney Island. We got there one Saturday as the aquarium opened and there was a sign posted to the glass tank. The baby beluga had been born dead. The mother, the sign read, was recovering but would be fine. We read the sign in shock and watched the single beluga whale in her tank. She was circling slowly. Neither of us could speak. Suddenly, without warning, the beluga started to throw herself against the wall of the tank. Trainers came and ushered us out. We sat on a bench outside, and suddenly I felt tears running down my face. You saw, turned my face towards yours, and kissed me. We had never kissed before, and I let my lips linger on yours for a second before I stood up and walked towards the ocean. It was too much – the whale, the death, the kiss – and I wasn't ready. Forgive me – I don't think I ever understood what an emptiness you would create when you left and I realized that that kiss on Coney Island was the first and the last. Are you out there, dear friend? If so, please respond. I think of you, and have thought of you often, all of these years. An ailurophobe's delight circa 1982.  "If you want to concentrate deeply on some problem, and especially some piece of writing or paper-work," Muriel Spark advised, "you should acquire a cat." But while felines may have found their way into Joyce's children's books, Indian folk art, and Hemingway's heart, their cultural status is quite different from that of dogs, which are in turn celebrated as literary muses, scientific heroes, philosophical stimuli, cartographic data points, and unabashed geniuses. In fact, there might even be a thriving subculture of militant anti-felinists -- or so suggests A Cat-Hater's Handbook (public library), a vintage gem by William Cole and beloved children's book illustrator Tomi Ungerer, originally conceived in 1963, but not published until 1982. The back cover boasts: "If you want to concentrate deeply on some problem, and especially some piece of writing or paper-work," Muriel Spark advised, "you should acquire a cat." But while felines may have found their way into Joyce's children's books, Indian folk art, and Hemingway's heart, their cultural status is quite different from that of dogs, which are in turn celebrated as literary muses, scientific heroes, philosophical stimuli, cartographic data points, and unabashed geniuses. In fact, there might even be a thriving subculture of militant anti-felinists -- or so suggests A Cat-Hater's Handbook (public library), a vintage gem by William Cole and beloved children's book illustrator Tomi Ungerer, originally conceived in 1963, but not published until 1982. The back cover boasts:  What's so cute about an animal that loves absolutely nothing, makes your house smell terrible, and has a brain the size of an under-developed kidney bean? At last, a book that dares to answer these and other feline questions with the sane and sensible answer: What's so cute about an animal that loves absolutely nothing, makes your house smell terrible, and has a brain the size of an under-developed kidney bean? At last, a book that dares to answer these and other feline questions with the sane and sensible answer:Not a damned thing! Cole writes in the introductory pages:  Ailurophobia is, dictionarily speaking, a fear of cats. But words have a way of gradually sliding their meanings into something else, and ailurophobia is now accepted as meaning a strong dislike of the animals. Ailurophobes abound. Quiet cat-haters are everywhere. Often, a casual remark that I was doing anti-cat research would bring sparkle to the eyes of strangers. Firm bonds of friendship were immediately established. Mute lips were unsealed, and a delightful flow of long-repressed invective transpired. It was heart warming to find that what I thought would be a lonely crusade is truly a great popular cause. Ailurophobia is, dictionarily speaking, a fear of cats. But words have a way of gradually sliding their meanings into something else, and ailurophobia is now accepted as meaning a strong dislike of the animals. Ailurophobes abound. Quiet cat-haters are everywhere. Often, a casual remark that I was doing anti-cat research would bring sparkle to the eyes of strangers. Firm bonds of friendship were immediately established. Mute lips were unsealed, and a delightful flow of long-repressed invective transpired. It was heart warming to find that what I thought would be a lonely crusade is truly a great popular cause.  What you'll find, of course, is that underpinning Ungerer's delightfully irreverent illustrations and Cole's subversive writing is self-derision rather than cat-derision as this cat-hater's handbook reveals itself as a cat-lover's self-conscious and defiant love letter to the messy, unruly, all-consuming, but ultimately deeply fulfilling relationship with one's loyal feline friend. |

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu