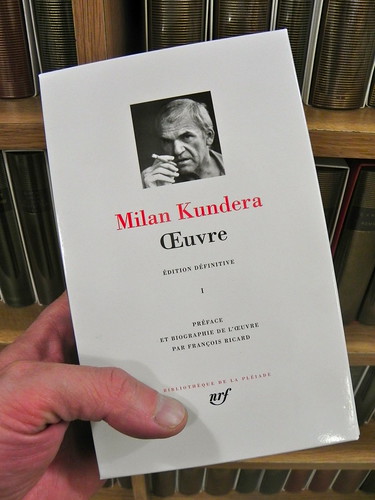

"Oeuvre", de Milan KUNDERA, a photo by armitiere on Flickr.

Fallait-il qu’il l’aime, la France, pour faire en R5 toute cette route depuis la Tchécoslovaquie – toute cette route vers la liberté! C’était en 1975, et c’était définitif, cette fois. De notre pays, il connaissait les classiques, ayant lu Rabelais, Breton et les surréalistes dans sa Moravie natale. Claude Gallimard en personne était allé lui rendre visite à Prague, remportant dans sa valise, clandestinement, le manuscrit interdit de «La vie est ailleurs». Kundera avait reçu, quelques mois plus tard, le prix Médicis étranger. «Je suis un bizarre auteur français de langue tchèque», avait-il conclu avec son ironie proverbiale.

(...) La Pléiade rassemble aujourd’hui son recueil de nouvelles («Risibles Amours», son livre auquel il est le plus attaché, dit-il), les grands romans qu’il publie entre 1967 et 2003, et puis ses essais. Ce qui frappe dans cette édition, c’est l’esprit d’équipe de la formation tout entière. La cohérence de la vision, et puis les obsessions: multiplication des points de vue (comme dans «la Plaisanterie»). Mélange des genres (Kundera n’écrit pas de romans politiques, mais des romans d’amour où l’on parle politique). Préférence marquée pour les figures féminines (les inoubliables Tereza et Sabina de l’«Insoutenable Légèreté»). Et puis cette manière qu’il a (héritée peut-être de Diderot, à qui il a rendu hommage dans sa pièce «Jacques et son maître») d’articuler imagination et réflexion comme face et pile d’une même monnaie romanesque.

N’est-ce pas le sentimentalisme qui accélère le vieillissement des œuvres? Il suffit de relire cette succession de chefs-d’œuvre aussi pimpants qu’au premier jour pour constater qu’il n’y cède jamais. Mission secrète du romancier: la célébration du plaisir sous tous ses aspects, et la guerre déclarée au pathétique (l’ennemi). Kundera ne se présente-t-il pas, dans «Jacques», comme «un hédoniste piégé dans un monde politisé à l’extrême»? Plaisir sexuel notamment, qu’il observe en naturaliste: voyez comme il décrit le corps de la «vendeuse du magasin d’articles de sport en location» dans «le Livre du rire et de l’oubli»: «Un appareil mobile à produire une petite explosion.» L’amour, chez Kundera, est une leçon de choses.

On inscrira donc, au fronton de cette édition définitive, ce slogan anti-slogans: le plaisir et rien d’autre. Ainsi va l’œuvre magistrale de Kundera, qui s’adosse aux grands dieux anti-lyriques du domaine romanesque occidental, de Rabelais à Sterne jusqu’à Kafka ou Joyce, et fait taire l’excès sentimental qui avait fini par faire du roman, aux XIXe et XXe siècles, un même fleuve nostalgique toujours en débord: «L’attitude anti-lyrique, c’est la conviction qu’il y a une distance infinie entre ce qu’on pense de soi-même et ce qu’on est en réalité; une distance infinie entre ce que les choses veulent être et ce qu’elles sont. Saisir ce décalage, c’est briser l’illusion lyrique. Saisir ce décalage, c’est l’art de l’ironie. Et l’ironie, c’est la perspective du roman.»

Didier Jacob pour bibliobs.nouvelobs.com

"Oeuvre", de Milan KUNDERA (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade), volume 1, 1 504 pages; 53 euros

120 euros les deux volumes sous coffret

WHEN THERE IS NO WORD FOR 'HOME'

WHEN THERE IS NO WORD FOR 'HOME'

THE Czech novelist Milan Kundera and his wife, Vera, live in Paris on a small street on the Left Bank, not far from Montparnasse. Their apartment is one of those top-floor Paris flats put together from a row of chambres de bonne, and it has all the charm of those attic rooms - the sunny mornings, the tin-pot rooftop views, the low ceilings and the bright white walls. Vera Kundera found it in Le Figaro on their first day in Paris, seven years ago, and she put in plants and hung the paintings they had managed to take out of Czechoslovakia when they left in 1975 for what was to have been a short stint at the University of Rennes, in Brittany, and ended as political exile. Two of the paintings are beautiful. Mr. Kundera says that the men who painted them were as out of favor with the regime as he was, and that no one he knows outside Czechoslovakia has heard of them - and not many people in Czechoslovakia, either. Mr. Kundera himself paints. When I called on him recently he showed me some of his gouaches: a head with a dancing hand for a body; a couple of melted faces; a hand holding out a bright dark eye; a lampshade on which two old men without their pants on engage in conversation.

Text:

Most of the gouaches date from the Kunderas' two years in Rennes; they needed something to brighten up a flat the university had rented for them, and Mr. Kundera bought some paints and paper and decided to decorate. He is 54 now, tall, lean as a cowboy, with pale eyes and straw hair faded into gray. On the streets of Montparnasse he even looks a little like an old cowboy, in the pair of jeans and the black shirt, buttoned to the neck, that have become a well-known Kundera costume. He is something of a celebrity here. President Francois Mitterrand has declared him a French citizen. His new novel, ''The Unbearable Lightness of Being,'' is on the best-seller lists. Liberation calls him ''cruel,'' ''elegant,'' ''virile,'' as if he were next winter's collection from Claude Montana or Thierry Mugler. I asked him about this curious notoriety:

How do you feel about the French making news out of you?

Not out of me, really. It may be that my books have become ''news.'' That is, they have become political occasions, not because they are about politics - they are not - but because the subject of news is by definition politics. For me, one of the most striking facts of modern life is the extent to which journalism - the news - has taken over the culture. Culture has been subjected to a vision of the world in which politics holds the first, the absolutely highest place, in a scale of values. So many people have that vision that by now they know their culture only journalistically - that is, they simplify; they reduce their culture to ''news,'' or, in other words, to politics. Not consciously. And often with the best will in the world.

And what happens to books like yours?

If I write a love story, and there are three lines about Stalin in that story, people will talk about the three lines and forget the rest, or read the rest for its political implications or as a metaphor for politics.

Then is it the West that has invented the genre we call ''dissident literature,'' and not you, the dissidents?

That's the paradox. When the culture is reduced to politics, interpretation is concentrated completely on the political, and in the end no one understands politics because purely political thought can never comprehend political reality. It's been 40 years since Yalta, and still no one really understands what happened there. This isn't a sentimental statement. It is certainly not a reproach. I'm not saying, ''Look, we in Central Europe suffer because of Yalta, and you don't suffer and so have no appreciation of our suffering.'' It's not a question of appreciation or compassion, of you being horrified for us or fighting for us or even protesting for us or making noises. It's purely a question of knowledge, of understanding.

We have never truly posed the question, ''What happened at Yalta?'' and that amounts to an immense na"ivete. You can't reproach someone for na"ivete. Who am I to reproach a Frenchman or an American who lives his own life quietly in his own town, in his own country? He can't suffer for someone else. He isn't made to live out someone else's fate. But he is made to understand. Quite simply, it is necessary for him to know, to reason, to comprehend what is happening to, say, people in Czechoslovakia. It's not a question of sympathy or empathy but of responding rationally so that his na"ivete won't become his tragedy. For example, we have the same regime in Prague or in Warsaw as in Moscow - we are the Soviet world, the Communist world, the totalitarian world, or whatever you call it - but of course taken historically, taken culturally, Warsaw and Prague are completely different from Moscow. To say that Prague under the Soviets is Eastern Europe is like saying that France, occupied by the Soviets, would be Eastern Europe. The drama of Czechoslovakia isn't merely the drama of a regime. Regimes are ephemeral. Regimes change. Yesterday there was a fascist regime in Spain and today, voila, it's gone. The real drama is that a Western country like Czechoslovakia has been part of a certain history, a certain civilization, for a thousand years and now, suddenly, it has been torn from its history and rechristened ''The East.'' The East is not Czechoslovakia or Poland or East Germany. The East, in Europe, is Russia, which knew neither the Middle Ages with its scholasticism and its philosophy nor the Renaissance nor the Reformation nor the Baroque - in other words which was never part of those thousand years of history. Take the great music of the West. You can forget France and Spain and even England but if you forget the middle of Europe you lose Haydn and Schoenberg; you lose Liszt and Bartok and Chopin.

Are you close to the Polish, close to their struggle?

I have total sympathy for Poland.

And for the Roman Catholic Church in Poland?

You know, when I was a boy I hated the church. I hated everything Catholic. Then one of my friends was put in prison because of his Catholicism, and it happened at exactly the time that I had trouble with the regime because of what I understood to be my atheism - because of skepticism and ''libertinage'' and contempt for conventions and all the other things forbidden by the Russians, who were, of course, also atheists. I understood then that what the Russians were forbidding was really Europe, that Catholicism and skepticism were the two poles that defined Europe, that Europe, so to speak, was the tension between them. And so my allergies changed, and my friends' allergies changed too, and we created a kind of spontaneous brotherhood. I began to see that the force of Catholicism in a place like Poland had to do with asserting that you are a European when you live on the frontier between the two churches - Western and Eastern - that in fact divide Europe from the East. You have to remember, too, how much Catholicism has changed since Pascal said that faith was a wager, and how much atheism - confident, Cartesian atheism - has changed with the knowledge that man is too weak to control his world. We are all in doubt now.

And doubt is what defines Western Europe?

Skepticism defines Western Europe.

Then as a European - a skeptic - you must be more at home here in France than you would be, say, in America, where so many Russian dissident writers have settled.

I'm a Francophile, an avid Francophile. But the reason I'm here is really because the French wanted me. I came to France because I was invited, because people here took the initiative and arranged everything. It wasn't the Germans or the English, it was the French. And I was lucky because I do feel good here - much better than I feel in, say, Germany.

It seems to me, though, that the questions you raise, the philosophy you draw on, even the music you use for your themes and references - that they are all very German. Your sense of home - das Heim- is German.

In French, of course, the word ''home'' doesn't exist. You have to say '' chez moi'' or ''dans ma patrie''- which means that ''home'' is already politicized, that ''home'' already includes a politics, a state, a nation. Whereas the word ''home'' is very beautiful in its exactitude. Losing it, in French, is one of those diabolical problems of translation. You have to ask: What is home? What does it mean to be ''at home''? It's a complicated question. I can honestly say that I feel much better here in Paris than I did in Prague, but then can I also say that I lost my home, leaving Prague? All I know is that before I left I was terrified of ''losing home'' and that after I left I realized - it was with a certain astonishment - that I did not feel loss, I did not feel deprived.

How would you describe yourself now? As an exile? A Czech? A Frenchman? A dissident writer or just a writer? Where are your roots as a writer?

I can make novels about this better than I can explain it. ''Home'' is something very ambiguous for me. I wonder if our notion of home isn't, in the end, an illusion, a myth. I wonder if we are not victims of that myth. I wonder if our ideas of having roots - d'^etre enracine- is simply a fiction we cling to. Take Sabina (Sabina is an artist, a character in ''The Unbearable Lightness of Being''). Sabina leaves Czechoslovakia to free herself of her roots. Her roots stifle her. She wants to escape from home, but what does this mean, to escape from home? Does it mean from family or from an oppressive country or from a certain weight of being? For Tereza (Tereza is the novel's heroine), everything beyond ''home'' is empty and dead.

And Tomas, your hero, gives up his Swiss exile - which means his freedom and his work as a surgeon - and follows Tereza back to Prague. Her presence in Prague draws him like a siren's song. Not a song of sex, but a song of ''home.''

Well, as I said, ''home'' is our national enigma. Czech literature, Czech mythology, is based on a glorification of the house, of the household, of das Heim.

Actually, this is true all over Central Europe, not just in Bohemia. The same adoration of the household exists in Austria and Hungary and maybe even Germany. You see it with Heidegger. You see it at a very exalted level, of course, but still you see it - this glorification of roots, this idea that life beyond one's roots is not life anymore. I suppose I've also been a victim of that poetry of the home - good poetry but also really terrible poetry. In '68, when my friends started talking about leaving, I avoided even the possibility of emigration.

I know that the Polish refugees here concentrate all their energies on Poland. The Hungarians who came after '56 still form a kind of community. What about the Czechs? You say there are a hundred thousand, maybe a hundred and fifty thousand refugees of Prague Spring. Are they a community? Are you part of that community?

For me, that was a serious choice, a choice I had to make right away. Do I live like an emigre in France or like an ordinary person who happens to write books? Do I consider my life in France as a replacement, a substitute life, and not a real life? Do I say to myself, ''Your real life is in Czechoslovakia, among your old countrymen''? Do I live somewhere outside the reality of this flat, this street, this country? Or do I accept my life in France - here where I really am - as my real life and try to live it fully? I chose France - which means that I live among Frenchmen, make French friends, talk to other French writers and intellectuals. There is such a rich intellectual life here, and for us that means a circle of friends who are themselves a kind of protection against these questions. It means that whether or not I'm actually ''at home'' in France, I have nice amiable friends with whom I am at home.

Your characters are rarely at home. They are always in some sort of moral or philosophical transit, when they are not actually going somewhere. Your ideas chase each other around. ''The Unbearable Lightness of Being'' is like a chase in which Nietzsche's ''heaviest of burdens,'' his idea of eternal return, is chasing Parmenides' idea of ''lightness'' around the world.

You know, I started this chase, this novel, 25 years ago. The idea was there, but I messed it up completely, ridiculously. All I was left with were two characters - the girl Tereza and the man Tomas - and one scene of Tomas looking out of a window and saying to himself einmal ist keinmal.

Meaning ''one time is no time.'' Once is not enough.

Meaning that man, living his one life, is condemned to that one fatal experience. He can never know if he was a good man or a bad man, if he loved anyone or if he had only the illusion of love. He gets older and older, entering each new moment of his life equally innocent, and then one day he is old without ever knowing what old age is. His old age is merely his newest experience. He enters it as stupid as he entered the world.

Einmal ist keinmal.

That is the idea that haunted me for 25 years.

What stopped you for 25 years?

At first, I was simply not prepared. When I got to France, I wanted to try again, but I was still not prepared. There were still only the two characters and the one scene and the question of weight and lightness. It was an irrational question, and I knew that even Nietzsche's idea of an eternal return was a rationalization of that irrational question. I looked for a form to express all this. I thought I would create a kind of counterpoint, a kind of polyphonic form. But you see the intention was much more complicated than the result. For instance, I wanted to create a counterpoint between Goethe and Bettina, his young admirer, but I gave up on it. In the end, all I knew was that I wanted to write a love story, and what Goethe and Bettina had taught me was that it is impossible to write a love story without writing a critique of sentimentality at the same time. I think you have to write about love with supreme skepticism. Sentiment - what you call feelings - is something ambiguous and often deceptive. There are ''genuine'' feelings at the core of every really big deception in private and political life. Feelings give you a reason to behave in a certain way, they justify you by justifying themselves. In politics, you see people doing unspeakable things, and they are usually people driven by very pure feelings, by very pure enthusiasms for ideas that are truly monstrous. It happens all the time in your own life. Sometimes I feel hatred. I yell. I pound the table. I think terrible things. I know my hatred is idiotic. I know it is a waste. I know it's demeaning and destructive, but I'm somehow justified in hating because I feel.

Of course, love is like this, too. The language of ''love'' is a language about feelings that justify bad behavior.

Which leaves love?

I would say whatever is left over after you apply skepticism to feeling - that's love. At least, that's the love that interests me as a writer.

What usually comes first - your people or what you call their themes?

Their themes. A character exists for me to explore a certain theme, a certain idea. Tereza, for example, is a woman who feels awkward about her body.

Elle n'est pas bien dans sa peau.

She is my way of asking, what is a body? Why do we have the bodies we have? In a way, having a body is the first real violence against us. For people like Tereza, this violence is at the center of life. Curiously, it is the details with which you usually describe a person - What does he or she look like? What does he or she wear? - that often seem superficial when you try to create a character. Take Tomas. There is absolutely no description of Tomas. You can imagine Tomas, but for my purposes it would make no sense for me to describe him for you, because the character Tomas has nothing to do with physical details. Tomas is only the details, the characteristics, which relate to his - call it his principal existential theme.

Let me ask you again, then, to describe yourself.

If I tried, I'd end up with nothing. In my life, in everyone's life, there are hundreds of motives, hundreds of themes, and I don't know which is the important one.

Certainly the fact that you are a Czech writer living in Paris - an intellectual who dissented and cannot go home - is important, whatever we may say about ''home'' and das Heim and chez moi.

The fact that I was allowed to leave is important. In the 60's, no one could leave Czechoslovakia. Then, suddenly, in the 70's, we could go. In fact, there was pressure - discreet but very stubborn pressure - to let people go. And since it was mainly the intellectual elite that could seriously consider leaving, we can only conclude that Russia had decided that intellectuals - people who thought by profession - were too dangerous to have around. This, of course, was very anti-Marxist - this sudden appreciation of the power of intellectuals and their moral force. Before, we had been thrown in prison, but now the Government was saying, in effect, that we were less dangerous to it in exile - writing and making speeches and even organizing against it - than we were silenced in our own country. It was an acknowledgement that even in prison we added to the undercurrent of disquiet in Czechoslovakia, that the country would always know we were there.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu