Via Flickr:

View at Artefact Festival, STUK, Leuven, february 2009.

www.artefact-festival.be/2009/

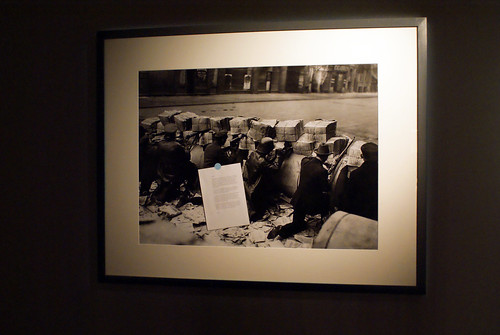

In 1919 Willi Römer photographed a fight in Berlin during the occupation of the press district by revolutionaries. We follow the path of the image from being a document of an historic event to a digitalised commodity of Corbis, one of the largest image archives and stock agencies (for fee-based download). On Corbis' website the image has the (incorrect) title "Revolution in Berlin - Forces loyal to the Kaiser and Imperial Government prepare to do battle against insurgents near end of World War I".

Corbis was founded by Bill Gates in 1989. The company owns more than 70 million photographs and has moved its analog collection to an underground storage space in a former limestone shaft in Pennsylvania. The company has as well purchased large (private) archives containing historically important photographs. Part of the collection was converted to a digital format‚ inscribed with a watermark‚ and posted on the company's website. This also happened with Römer's image. According to international law, the use of the photo had already long been public domain. Even following the sale and the removal of the watermark, the image exists under copyright due to the embedded watermark.

Ines Schaber highlights the interrelation between the image as private property and the writing of our common history. She exposes the potentially threatening, monopolistic-capitalistic appropriating of pictorial memory. On the original image she shows a letter that she wrote to Bill.

Text source :

www.artefact-festival.be/2009/099_expo_en.php?id=015

/////////

About a photograph and its circulation

Ines Schaber in conversation with Diethard Kerbs, Professor of the History of Photography, July 2004, Berlin

Ines Schaber:

Could you tell me what we can see on this photograph?

Diethart Kerbs:

The photo shows Berlin’s Schützenstrasse during the occupation of the press district on the 10th or 11th of January 1919. What we have here is a press photo which was also published as a photo-postcard. The photo was most likely taken by Willy Römer, a press photographer from Berlin who had just become independent in the winter of 1918/19. It is apparent from the shot that the photographer took the picture from the entrance of the Mosse Publishing House aiming his camera towards the outside. Of course, this is not a real fight scene; the photographer probably ran around during the quiet intervals and said: “stay sitting down like you are sitting now, I will take a picture of you”. If shots were being fired, he couldn’t have stood there taking photos like that, because he would have probably been hit by the bullets of the government troops. It is interesting to note the random composition of the group in question: marines, soldiers, people dressed as civilians who jointly keep the Mosse Publishing House under seizure. Through this the government troops and revolutionaries can always be easily distinguished: the former are equipped with perfect combat gear, while the latter are usually haphazard groups of people.

IS:

You say that the picture was shot from the inside to the outside. Does this mean that the revolutionaries trusted the photographer and believed that it was important for them to be photographed?

DK:

That’s hard to say. Above all, they were only fighting. Whether they were media-conscious in the dual sense – in other words, whether they were, on the one hand, consciously aware of the importance of photographically documenting the revolution, which would later be made public worldwide, and, on the other hand, knew or suspected that having been photographed, they would become identifiable and later, if nothing came of the revolution, may be lined up against the wall for it – is difficult to say. In any case, in the spring of 1919, no one was called to account based on photographs, but anyone with a gun in their hand was shot. More than 80 % of those who died in the revolution were not victims of the fighting, but were shot later for having fought or because they had been injured, or sometimes because they had a scar on their shoulder where the gun they walked the streets with had rubbed it raw. The soldiers simply tore the workers’ shirts open and whoever had a mark like that on his shoulder was stood against the wall and shot. Willy Römer probably did not anticipate that the police or the army would come and confiscate his photos. In any case, almost all of his photos of the revolution survived, even the one which documents his own arrest.

IS:

In accordance with the copyright laws that were in effect in 1919, Willy Römer’s photos were protected for 10 years, is that correct?

DK:

Yes, but this changed later. As I am no expert on copyright laws, I can only offer you anecdotes about it. However absurd it may seem, we own one of the forward leaps in lawmaking pertaining to photography copyrights to Adolf Hitler. Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s personal photographer and friend, with whom he was on a first name basis, went to see him and said: “I am doomed, the rights to my photos have expired. I can no longer make money with the photos that I took between 1910 and 1920. Now anyone can steal them.” Then Adolf allegedly said: “Alright, my friend, I will help you”. Thus, in 1940, the term of copyright protection was extended to 25 years. Willy Römer fought for the copyright of his photos after World War II. With the help of the Berlin Journalist Association, he filed complaints each time one of his photos was used in a TV movie or a documentary and he was not paid. The usual response was that the photos had already been in their possession or that they got them from someone – even from the photographer himself – years before, or that they had no idea they were Römer’s photographs. Most times they managed to find an excuse. Sometimes he was even invited to sue. Willy Römer fought these battles for the recognition of the authorship of his photos, as well as the royalties due him. After 1945, his financial situation became dire. He could no longer keep up with his younger colleagues as an up to date press photographer. In 1947, he turned sixty. He lived for another 32 years. He attempted to make a living by putting his photos in circulation, but he received virtually no money for them. Following a few instances of protestation at the Ullstein Photo Agency, he was told “Fine, since it’s you and we know you, we will do as we had done before, 50:50.” Ullstein still has originals by Römer from the time of the revolution.

IS:

What do you mean by “originals”? Original prints or original negatives?

DK:

Both, in fact. Of course, negatives are “the more original originals”. One can still make copies from a glass plate today. But the more valuable originals are the so-called vintage prints, held in such high esteem by auction houses and art dealers. These are the original prints made by the photographer himself at the time the photo was created.

IS:

How did you acquire Römer’s photos?

DK:

Willy Römer became very old. Until his death in 1979, he took care of his archive and made supplementary labels for his photographs. In 1981, I discovered the archive by accident when I saw it advertised for sale in a newspaper. The family needed money. Römer’s wife had a pathetically small pension and his daughter did not live in Berlin. They wanted to sell it to ensure the old-age pension of the mother. They had tried all possible institutions in Berlin –the photo bureau and the archives of the province, the Berlinische Galerie, the Ullstein Photo Agency, the Bertelsmann Encyclopedia Publishing House, the Pan-German Ministry, etc. – but they were not able to find a home for the archive. When I learned of this, I also made an attempt to find a taker for it, but to no avail. I was turned away by everyone. No one had the wish or the ability to handle and take care of such a large mass of photos. I, on the other hand, became very interested, and, with great difficulty, scraped enough money together to purchase the archive myself. Then, together with a few of my friends, we founded the Working Group for Image Source Research and Contemporary History (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Bildquellenforschung und Zeitgeschichte e.V.). This nonprofit organisation operates the so-called Agency for Images of Contemporary History (Agentur für Bilder zur Zeitgeschichte), which has a very small staff. It, in fact, consists of a single young lady for whom this is a source of supplementary income. Our profit is so meager that it is negligible in terms of taxes. It usually remains under EUR 4000 per year, which we make by loaning out copies. One half of the money is given to this lady and the rest is used to care of the stock and to finance research.

IS:

Is it possible to view these photos and to conduct research in the archive?

DK:

No, it isn’t. The archive is located in a small room of a private residence. We are not equipped to receive visitors. The archive is basically a private institution, anyway it is neither a public archive, nor a commercial company. You have to make a very specific inquiry– as accurately as possible – what motifs you are looking for. Then, we can find the images and show them to you. This is, of course, only possible if the visitor articulates a specific, professionally supported request. The location and the shortage of time do not make it possible for us to receive visitors who wish to “just have a look around”.

IS:

How do you define the terms ” rights of use” and “copyright”?

DK:

Copyright is the same as in the case of a book. Through copyright, the author reserves all rights relating to the text. The author may also confer these rights, if he wishes, to a publisher, for example. Usually, when publishers release a book, they want to acquire the copyright for themselves. This, however, means that they bear the financial risk but also the possible profit. Thus, copyright is the right connected to a text or a photograph.

IS:

Photos are very different from books in terms of accessibility.

DK:

Yes, they are. And there is a historical reason for this. The invention of photography was made public news in 1839 and, very generously, donated to humanity by the French government. They said: “We have bought the rights and we relinquish them… now you may all take photographs”. This was a great, cultural gesture of the French government. It did not, however, go as far as establishing a phototheque, a library of photographs. Public libraries came into existence almost immediately, as bourgeois revolutions opened up the royal libraries. However, the bourgeois states never declared of their own volition: “now we will begin to collect all those photographs that are of significance to us in order to render them at the disposal of the public”. The fact that photographs are also part of the cultural wealth, and that they should generally be made available to the whole of society, was forgotten. We are still at this level today. Bourgeois society has neglected to establish the availability of photographic resources as a general right to education the way it managed to do this for literary resources.

IS:

How does this relate to the copyright of photographs?

DK:

In the case of photographs, copyrights can be owned for 50 years after the creation of the photo, or for 70 years after the death of the author. A distinction is made between functional and art photography. All photographers who wish to secure the rights for 70 years after their death refer to themselves as photo-designers.

Willy Römer’s shots are press photos – but this can be disputed. We have the example of Dr. Erich Salomon, who was a learned lawyer. During the unemployment of 1929, he worked as a clerk in the advertisement department of Ullstein Publishing. He began to take pictures in order to photograph the advertising surfaces they offered for rent. Then he began to enjoy photography and started taking press photos for Ullstein Publishing. Within two years, he became one of the most famous German press photographers. As a Jew, he immigrated to the Netherlands during the Nazi years and was later murdered. His son was successful in getting two suitcases full of his photos to England and, after the war, discovered the remainder of his inheritance in an attic in the Netherlands. This inheritance was sold for 1 million Deutsche Marks to the city of Berlin in 1975. This is, of course, a special case. Salomon was a member of the Jewry of Berlin and a victim of Fascism, as well as an excellent photographer. Furthermore, the photos show important figures of history. These four factors add up to the high value of the photos. No one today would dispute the rightfulness of the purchase and the value of the pictures. If, however, we were to interpret the story more strictly, we would have to say that these are press photos.

IS:

The debate of whether or not to declare something as art often only takes place during the battle over the rights.

DK:

The definition is, as a matter of fact, quite simple and the question, for me, is easily answered. Art is everything that is found in museums, presented in galleries, offered and bought by art dealers, critiqued by art critics, and accepted as that by the international art market regardless of where it came from and who made it. There is nothing to dispute here, society has already decided.

IS:

Does this mean you would answer the question whether a photograph is art or not, through the

market?

DK:

Yes, to a great extent. Being that we live in capitalism. It is a function of social use. As Luhmann would say, it is a system within the social systems. This is a pragmatic definition, it saves one from the theoretical debates. At the beginning of the seventies, even in bourgeoismagazines, like the ZEIT, there was a heated debate on whether art was a “commodity”. Then this rapidly abated, as an economic-social revolution failed to ensue. A society will not immediately change its economic structure only because a few intellectuals decide on pondering it.

IS:

In your running of the Agency for Images of Contemporary History, do you not get caught in the bind between private property and the demand for public access?

DK:

Of course, I do. Society (or, if you prefer, the state), on the one hand, would have to make sure that photographs, or visual information that bear historical and cultural significance, are generally made accessible so that all those interested and wanting to learn can see them. On the other hand, those who took these photos and those who preserve them should be protected against theft and exploitation. Their work should be safeguarded and rewarded by society. So far the state has done this very poorly. This goes for all photographers, be they artists or press photographers. The public is not even aware of this problem yet.

IS:

Accessibility to photographs also opens the possibilities for titeling and thus naming them. Bill Gates’ image stock Agency Corbis titles the photo we have talked about on their home page as “Revolution in Berlin”. Forces loyal to the Kaiser and Imperial Government prepare to do battle against insurgents near end of World War I.”

DK:

This is interesting – and completely false. This way the fronts are, in effect, swapped. This was probably written by someone who didn’t have the slightest idea about the story of the Berlin revolution. The problem of erroneous photo titles is as old as the profession itself. The texts say whatever happens to suit the newspaper or the book author.

IS:

Can Corbis actually sell the photos?

DK:

It is handled like this.You must keep in mind that at the time about 100 prints entered circulation, plus photo-postcards, maybe about 300 copies. Of these, probably 30 or 40 have survived in various archives. Sometimes these too land at large companies, not much can be done about that. The photo we were talking about can be found at Ullstein or the photo archive of the Preussischer Kulturbesitz. Corbis has the technical advantage. If you want the same photo from us, you would have to call us, we have to look it up, and, in some cases, if we don’t want to part with the original, we would have to make a reproduction. All this takes about 14 days and only then can the reproduction or the print be sent out. Then we have to chase you down so that you return the photo to us. This is an ancient method. What we do is 20th century, what Corbis does is 21st century. They send the photo to your screen in a matter of seconds.

IS:

And what are you doing?

DK:

The way we handle this at the Agency for Images of Contemporary History – is our cultural, social, and political decisions and orientation. We also, of course, decide what we do and don’t want to circulate. We also have a couple of photos by horrible Nazis. We don’t necessarily have to publish these. This is the difference, and this is our decision. We have the freedom to say no and to forgo profit – the money that comes in from advertisement, for example. But as I have said, the business side of this is rather underexposed in our case, while for Gates, Getty and others, it is the main direction. For me it is mostly about the preservation of valuable, historical photo stocks and its integration into public-cultural use. To this end, we mostly organise exhibitions and publish books, and it is for this purpose that I write about this topic in newspapers and journals.

Text source :

www.artefact-festival.be/2009/099_expo_en.php?id=016

Traducere // Translate

Ines Schaber : Culture is our Business (2004)

Abonați-vă la:

Postare comentarii (Atom)

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu