The self-made man, working his lonely way by night through the best the world's thinkers had to offer, was an attractive cultural icon of the early 20th century. The masses' thirst for betterment spurred intellectual popularisers such as HG Wells. Voracious readers from the lower orders spent their pennies not only on primers and surveys but on series designed for them, such as Dent's Everyman's Library or Grant Richards' World's Classics, that offered the original texts themselves in cheap editions. Nor, of course, was this thirst for knowledge and self-improvement an exclusively British phenomenon. As is readily apparent from Timothy Ryback's thoughtful and oddly intimate book, it existed in central Europe, too. Anyone familiar with the obsessive drone of his wartime Table Talk or Mein Kampf will have already suspected what is amply demonstrated here: Adolf Hitler was the ultimate autodidact.

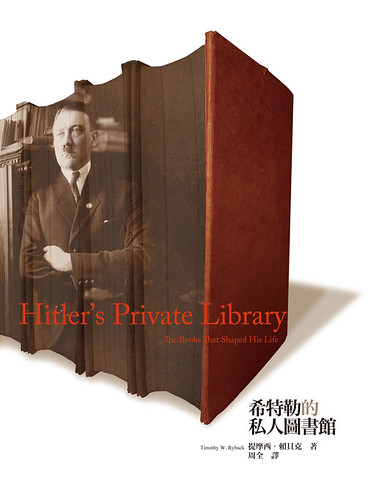

Hitler's Private Library begins with the striking image of the 26-year-old Hitler, serving at the front in northern France, walking into the nearest town during a lull in the fighting – to buy a book. How did the young serviceman plan to pass the time, when not dodging enemy fire delivering messages to the front? By settling down with Max Osborn's popular architectural history of Berlin. Three decades later, he and his court architect, Albert Speer, would relax during the second world war by poring over scale models of the Berlin of the future; but in 1915 he was already a keen devotee of the subject. The volume that the young soldier bought in Fournes survived both wars: and it is just one of the items intelligently discussed by Ryback both as object and as guide to its owner's interests and obsessions.

Books surrounded Hitler his entire adult life – though whether they opened his mind and formed his worldview or simply bolstered opinions that had already germinated is open to doubt. What is not in question is their importance to him, evident long before the party hacks sent in their endless complimentary volumes to clutter the shelves in his private residence. Books had travelled with him from the outset of his political career. Indeed, in the modest Munich apartment he rented after resigning his army commission, his first piece of furniture was a wooden bookcase, quickly crammed with cheap detective novels, military histories and memoirs; on its shelves, Montesquieu, Rousseau and Kant rubbed shoulders with anti-semitic philosophers, nationalists and conspiracy theorists. The future Führer was improving himself for all he was worth, for in Kultur-proud Weimar Germany even a rightwing revolutionary had to overcome the deficiencies of an abbreviated education if his poor grammar, bad spelling and other howlers were not to cost him the command of the beer-hall battalions and hand over leadership of the growing Nazi movement to his intellectual superiors.

In the 1930s, as his political fortunes improved spectacularly, and with them his income from the sales of Mein Kampf, Hitler spent more and more on books until they became one of his largest items of expenditure. By the mid-1930s, he had thousands. And the nightly read continued to the very end: piles of books crowded even his spartan last bedroom in the Berlin bunker. In the photos taken by US servicemen they can be seen by the bed where he finished up, slumped in a pool of blood next to the corpse of Eva Braun-Hitler.

Ryback is not primarily interested in itemising the works in Hitler's possession; others have done that and in doing so missed what he offers – a careful perusal of individual volumes that were either marked up by their owner or personalised with dedications offered to him by their authors. In terms of content, there are few surprises: Hitler's pencil was drawn to pronouncements on the nature of genius and the importance of leadership; the books that languished unread included a biography of Gandhi and a massive collection of the latter's prison writings. Many passages provoked him to violent scrawls of outrage. But both agreement and disagreement prompted the pencil. We almost catch the man in the act after he has retired to bed for the night, his reading glasses, book and pot of tea already laid out for him by the servants. It is easy to laugh at all of this, to mock Hitler for his pedantry and his ignorance. But his accumulated knowledge had real-life consequences. Military matters, for instance, dominated in his private library, and his keen reading of the biographies of great generals and contemporary almanacs of military equipment helped to give him a confidence by 1939 that he had lacked 20 years earlier. Now, he was not afraid to stand up to his own advisers, and the result was a war that tore Europe apart.

Hitler's friends from his early years always associated him with books and stressed that it was a "deadly serious business" for him. One thinks of those heavy yet largely unread thinkers, those busts of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche that the Führer liked to surround himself with, the great encyclopedias that he consulted constantly. As an approach to turning the Führer back into a real human being, of his time and place, Ryback's strategy works rather well. Yet what we are left with is not the mysterious cipher that some of Hitler's recent biographers have offered us so much as a dull and slightly depressing petit bourgeois with a chip on his shoulder.

Mark Mazower

Traducere // Translate

Hitler's Private Library

Abonați-vă la:

Postare comentarii (Atom)

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu