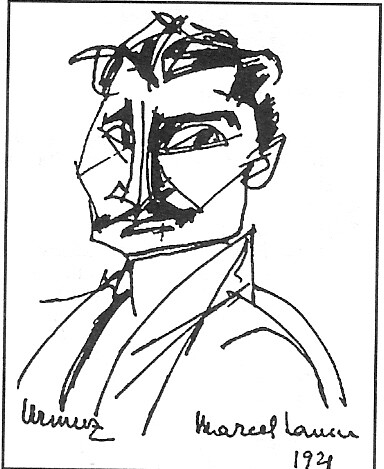

Iancu, Marcel (1895-1984) - 1921 Portrait of Urmuz, a photo by RasMarley on Flickr.

The Funnel And Stamate

by Urmuz (Dem. Dumitrescu-Buzău) (1883-1923)

I

A well-ventilated apartment consisting of three rooms, glass-enclosed terrace and a door-bell.

Out front, a sumptuous living-room, its back wall taken up by a solid oak book-case perennially wrapped in soaking bed-sheets… A legless table right in the middle, based on probability calculus and supporting a vase containing eternal concentrate of the “thing in itself,” a clove of garlic, the statuette of a priest (from Ardeal) holding a book of syntax and 20 cents for tips… the rest being without interest whatsoever. This room, it should be noted, which is forever engulfed in darkness, has no doors and no windows; it does not communicate with the outside world except through a tube which sometimes gives off smoke and down which, nights, one can have a glimpse of Ptolemy’s seven hemispheres, and daytime, two human beings in the process of descending from the ape by the side of a finite string of dry okra right next to the infinite, and useless, Auto-Kosmos.

The second room is in the Turkish style; it is decorated in the grand manner and furnished with the most fantastic items of eastern luxury… Countless precious carpets, hundreds of old arms, the strains of heroic blood still on them, lining the colonnades; the walls, according to the oriental custom, are painted red every morning as the are measured, occasionally, with a pair of compasses for fear of random shrinkage.

From this area, and by means of a trap door on the floor, one reaches an underground vault, and on the right, after traveling on a little handledriven cart first, one enters a cool canal one branch of which ends no one knows where, the other leading precisely in the opposite direction to a low enclosure with a dirt floor and a stake in its center to which the entire Stamate family is tethered.

II

This dignified and unctuous man, whose shape is roughly elliptical, and who, on account of the extreme case of nerves he got by working for the city council, is forced all day long almost, to keep chewing on raw celluloid which he expels in salivated crumbs over his only child, a fat, blasé boy of four called Bufty. Out of a strong sense of filial duty, the little boy pretends not to notice anything and drags a small stretcher on the ground as his mother, the tonsured and legitimate wife of Stamate, joins in the communal revels by composing madrigals that are signed by the application of one finger.

Exhausting occupations of this kind make these people, literally, seek to amuse themselves by occasionally and daringly, reaching states of unconsciousness as all three of them would peer through binoculars through a crack in the canal, at Nirvana (situated in the same precinct as they, and beginning just beyond the corner grocery), and throw bread crumb pellets or corn cobs at it. At other times they’d visit the reception room and turn on the faucets that are specially installed there, until the water reaches their eye level whereupon they all joyously fire pistol shots in the air.

As far as Stamate is personally concerned, the activity that keeps him busy in the highest degree is the nightly taking of snapshots in churches of elderly saints which he later sells at reduced prices to his credulous wife and, more to the point, to little Bufty who is independently wealthy. Stamate would not have practiced this utterly objectionable trade for anything in the world had he not been almost entirely destitute, which is what led him to join the army at age on already so he could be the soonest of assistance to his two needy kid brothers, whose haunches protruded so badly they were both kicked out of their jobs.

III

It was on one of those days while Stamate was engrossed in his usual philosophical investigations when he thought, for a fleeting moment, that he put his finger on the other half of the “thing in itself,” whereupon he was distracted by a woman’s voice, a siren’s voice, which spoke straight to the heart and was audible at a great distance before growing fainter like an echo.

Running frantically to the communications tube, Stamate saw, to his befuddlement in the warm and balmy evening, a siren of seductive movements and voice stretching her lascivious body on the hot sands… In battle with himself, that he might not fall prey to temptation, Stamate rushed to rent a boat and set off on the open sea after plugging his own as well the sailors’ ears with wax…

The siren became even more provocative… She followed him over the watery main, singing and motioning lubriciously, until about a dozen dryads, nereids, and tritons had time to get together from the far, wide and deep points of the sea and bring up, onto a superb seashell, an innocent and all too decent looking rusty funnel.

The plan to seduce the chaste and studious thinker could well be considered a success. He barely managed to steal back to the communications tube; the sea goddess graciously left the funnel on his doorstep before vanishing, with every one else in that company, amidst laughter and giggles, over the watery expanse.

Stamate, driven to his wits’ ends, confused and divided, just made it to the canal on his little cart… Without entirely losing his cool he cast dirt over the funnel a couple of times, helped himself to an infusion of sorrel, he fell, diplomatically, face down on the ground, lying there unconscious for a period of eight free days, which was the necessary term the civil authorities believed should pass before he could come into possession of the object.

After this time went by, and after Stamate returned to his day to day business and upright posture, he felt completely reborn. He had never experienced the thrills of love before. He felt he was a better and more tolerant man, and the turmoil he experienced at the sight of that funnel made him suffer and cry like a child. He dusted it with a rag, swabbed iodine on the larger holes, he took it with him and secured it by means of flowers and lengths of lace close to and in alignment with the communications tube and it was then tat, consumed by his feelings, he shot, lightning fast, through it, stealing a kiss on his way.

The funnel, to Stamate, had become a symbol. It was the only being of the feminine sex equipped with a communications tube which could allow him to satisfy both the needs of love and the higher interests of science. Oblivious of his sacred duties as father and husband, Stamate each night would cut the ties that kept him tethered to the stake with a pair of scissors thus giving free rein to his boundless love; he began therefore to pass more and more frequently through the interior of the funnel, fanning himself with a specially constructed trampoline, then descending vertiginously fast with a wooden ladder in his hands at the top of which he would sum up the results of his researches on the outside.

IV

True happiness is always short lived… On a certain night when Stamate had come to do his customary amorous duty, he found out to his surprise and disappointment that, for reasons no that clear to him yet, the orifice leading out of the funnel had become so obstructed that any communication through it became impossible. Dumbfounded and suspicious he lay in ambush, and on the following night, doubting his own eyes, he saw, to his horror, that Bufty had climbed up and, all huffing and puffing, had been let in and through. He was stunned; Stamate could barely gather the strength to tie himself to the stake; next day, however, he took a singular decision.

He first embraced his devoted spouse, and after giving her a coat of paint in a hurry he sewed her inside a waterproof bag so he could further preserve the cultural traditions of his family intact. On a cold and dark night, next, he took the funnel and Bufty and, throwing them both onto a tramcar that happened to be passing by, he waved them disdainfully of to Nirvana; later on, though, he managed, with the help of science and his own chemical calculations, his paternal feelings having prevailed in the meantime, to have Bufty appointed as bureau sub-chief over there.

As for Stamate, our hero, peeping for one last time through the communications tube, he took one more sarcastic and condescending look at the Kosmos.

Getting then into the handle-driven cart for the last time, he took off for the mysterious end of the canal where, moving the handle with ever-increasing speed, he has been running, insanely, to this day, steadily decreasing his volume in the hope that he may, one day, penetrate and disappear into micro-infinity.

English version by Stavros DELIGIORGIS

After The Storm

by Urmuz (Dem. Dumitrescu-Buzău) (1883-1923)

The rain stopped and what was left of the clouds had scattered completely… He wandered in the dark night with his clothes wet and his hair unkempt looking for a cranny he might take shelter in…

He arrived, without knowing, at the crumbling and time-caried crypt of the cloister, which he approached warily, smelled and licked it about 56 times in succession without getting any results.

Feeling frustrated he grabbed his sword and rushed into the cloister’s courtyard… But he was softened right away by the meek look of a hen that came out to meet him and which, with a timid motion that was full of Christian charity, invited him to wait for a few moments in the chancery… Having gradually calmed down, moved to tears, and gripped in the shivers of repentance, he gave up all and any plans of revenge and, after kissing the hen on the forehead, he put her in a secure place for safe-keeping. He took to sweeping all the cells and scrubbing their floors with rubble.

He counted his loose change and climbed on a tree to await the dawn. “How brilliant! How grand!” he exclaimed in ecstasy before nature, occasionally coughing pointedly and leaping from bough to bough as he periodically released some flies in the air under the tails of which he had attached long strips of fine writing paper.

His happiness though did not last… three passers-by who first pretended they were friends of his, and in the end claimed they had gone there on assignment from the internal revenue office, started giving him all sorts of trouble and questioning, first off, the right itself of climbing a tree…

But to show their good upbringing, and to avoid making direct use of the structures the law set at their disposal, they tried through all sorts of obligque means to force him to leave the tree… first by promising him a stomach rinse on a regular basis, but throwing in, as well, bagfuls in rent, aphorisms, and wood shavings.

He was unmoved, however, by all these enticements, and confined himself to taking out his certificate of indigence which he happened to have on his person that day, and which, among other exemptions, entitled him to squat on a tree branch absolutely free of charge for as long as he wanted…

Nevertheless, to show them that he harbored no hard feelings toward them, and to teach them a subtle lesson in tactfulness and urbaneness, he came down, took his sword off and went of his own free will into the muddy and infected pond nearby where he swam hare-like for one hour; instantly the embarrassed and humiliated fiscal commission took to its heels spreading, wherever it went – towns, hamlets, plains and mountains – one pestilential fiscal stink.

Pained and disheartened after the trying hard times he had been through, he counted his loose change and once again climbed on the tree from where he could survey the entire terrain, this time, and smiled cynically…

Then, regretting deeply what he had done, but having gained a lot morally, he came down, dusted himself with a tape measure, and singing the hymn to liberty and sticking the hen under his smock, vanished with it in the deep dark…

It is believed that he took the road to his native village where, fed up with living as a bachelor, it is likely that he decided to make a home for himself and the hen, and to make himself useful to his folks by teaching them the art of midwivery.

English version by Stavros DELIGIORGIS

Going Abroad

by Urmuz (Dem. Dumitrescu-Buzău) (1883-1923)

The greatest part of the various preparations for the trip had been completed; in the end he even paid the rent with the assistance of the two old ducks of his who did not let him down when he was about to lay himself out to the neighbors’ charity. Their only request, in exchange, was that they would be received for an hour at least every day in his studio which used to exude such a sweet and intoxicating smell from its window-frames. He boarded the ship.

He could not fight the paternal feelings that swept him back to the shore; there he motioned aimlessly and, in the midst of the beloved people, he sewed two blotting tampons on the musty lining of his tuxedo, and without wasting any time, stole unnoticed into the lowly room in the back of the yard and converted to Judaism.

He had no time to waste. He had entered the seventieth year of his existence leaving a glorious past behind him but expecting a limited number of days ahead. His only remaining wish was to celebrate his silver anniversary. He called all the hired hands to him, and after asking them to feed on some hemp seeds, he threw them into a font. Three tenured, grade three employees and one archpriest followed! Thinking that he might pacify the crowd that had begun to bitch, he sprained three fingers of his own left hand and climbed an a cobbler’s threelegged stool where he could rest, to everybody’s satisfaction at last, his silk-smooth bill floating and rolling freely and undisturbed on the cold and fresh water of the crystalline stream.

He then went on board once more. His aged wife refused to go along, gnawed as she was by the canker of jealousy on account of the love ties she suspected he had with a seal. Still, minding her duties as a wife, and so she wouldn’t be considered poorly raised, she gave him, on his departure, two flat-breads, a sketchbook of Borgovanu’s, and a kite complete with love-seat backs which he angrily rejected by shaking a few filberts in a sack.

An ambitious woman herself and unable to bear the affront of such a rejection, the renegade wife tied him with a rope by the cheek-bones, rudely dragged him to the boat’s edge and delivered him unceremoniously on dry land.

Fed up with life, and groaning under the weight of glory and age, he took off his fur cap and made his final resolutions which were also his last will. He gave up all his titles and wealth, he tool all his clothes off except for a linden bark rope around his waist, then, casting one more look at the boundless sea, he got on the first covered wagon that came his way and, reaching the nearest town in a gallop, proceeded to join the local Bar Association.

CONCLUSION AND MORAL

If forty winks is what y’all want to catch

Exchange no postcards with that mayor of Kurlygatz.

English version by Stavros DELIGIORGIS

Emil Gayk

by Urmuz (Dem. Dumitrescu-Buzău) (1883-1923)

Gayk is the only civilian with a rifle carrier on his left shoulder. His neck is drawn in and his morale very high. He will not be hostile towards anybody for long, but from his way of eyeing you, the direction his pointed nose takes sometimes, the air about him that he is being perennially pockmarked and the fact that his nails are uncut, you get the impression that he is ready at any time to lunge at you and peck you.

Pointed at both ends and bent like a bow, Gayk always stoops slightly forward so he may dominate his surroundings more easily. He believes in being prepared against any eventuality, which is why he sleeps only in tails and white gloves tucking a diplomatic letter under his pillow, a respectable quantity of tack, and… a machine gun.

In the daytime Gayk can stand no other garment except a small drape with festooned trim, one in front and one in the back, easily pulled aside by anybody with his permission.

He spends his time swimming non-stop for 23 hours but only from North to South for fear of coming out of his neutrality. In the free hour that is left to him he draws inspiration from muses in ankle boots.

He succeeded, early on, in giving our foreign policy a new direction, being the first to state with authority that we have to take the Transylvanians without Transylvania; he also maintained that we had at all costs to get a hold of Nasaud plus three some kilometers through the intervention of the Vatican, the three kilometers lying, however, not around a certain area, but lined up, one next to the other, lengthwise, close to the city and pointing towards the Duchy of Luxembourg, as a sign of reprimand that it allowed its neutrality to be violated by the German troops.

Gayk is childless. When he was in junior highschool, though, he adopted a niece of his at a time when she was weaving on a hand-loom. He did not hold back from giving her a select education – taking care to send a waiter to her daily who would beg her on his behalf to wash her hair every Saturday and to give herself, by whatever means possible, a generalist’s education.

The niece, a hard-working and conscientious girl, became an adult in no time and noting, on a fine day, that she did get her generalist’s education she asked her beloved uncle to release her from the boarding house and let her make her home in the fields… Encouraged by the response to her requests she did not hesitate to ask him, only a short time later, to guarantee her access to the sea. Gayk, then, instead of answering, leaped on her suddenly and pecked her countless times; this she considered to have happened without any preliminary warning and contrary to all international practice, and therefore instituting a state of war; a war in which they were engaged form more than three years and over a front that was almost seven hundred kilometers long. They both fought carrying food in the form of money; they fought with great heroism, but in the end Gayk having been made marshall of the battlefield and finding no military outfitter to put his new stripes on, decided not to fight any more and asked for peace. This suited his niece fine; she had just then grown a boil and saw her retreat cut off, the non-aligned being unable to send her the beans or gasoline any longer.

They held their first exchange of prisoners at the cash register of the theater of operations and got moderate prices for them. They then convened for the signing of a shameful peace treaty. Gayk agreed henceforth not to peck anybody, settling for the quarter of a liter of grain feed his niece undertook to bring him daily with the guarantee and supervision of the Great Powers; his niece on the other hand, at long last, received a strip which was two centimeters wide and reaching all the way to the sea, but without the right to dispense with swimming trunks. In the end, however, both were thoroughly satisfied, since a secret clause in the treaty gave them both the right to raise their morales in the future to the highest possible point.

English version by Stavros DELIGIORGIS

The Fuchsiad. An Heroic-Erotic Musical Poem In Proseby Urmuz (Dem. Dumitrescu-Buzău) (1883-1923)

I

Fuchs wasn’t quite born by his mother… In the beginning, when he came into being, he wasn’t even seen, he was only heard, for Fuchs, upon being born, chose to come out through one of his grandmother’s ears, his mother having no musical ear to speak of…

Fuchs then went directly to musical conservatory… Here he took the form of a perfect chord, after which, out of artistic modesty, he first spent three years in the depths of a piano unbeknownst to anybody, then, coming to the surface, studied harmony and counterpoint, and graduated in piano playing… He came down, next, but found out, contrary to all his expectations, and to his chagrin, that two of the sounds he was composed of had suffered alterations with the passing of time and had degenerated, one of them to a moustache with spectacles reaching behind the ears, and the other to an umbrella – both of which, together with a G sharp that was still left him, gave Fuchs his precise, definitive and allegorical form…

Later, in his puberty, it is said, Fuchs grew some kind of genitals which were but one young and exuberant fig leaf that made him uncommonly shy since he would have only given himself at the very most a flower or something no matter what…

This leaf has been his daily food as well, it is believed. The artist ingests it every evening at bedtime; not a worry on his mind, he descends to the bottom of his umbrella, and after locking himself up by using two musical keys, he sleeps transported by musical staffs, rocked on the wings of angelic harmonies, and beguiled by dreams heard well into the following day, when – shy as he is – he will not get out of the umbrella unless a new leaf has grown in its place.

II

At one time Fuchs had to have his umbrella repaired, so he was obliged to spend the night out in the open air.

Night with its mysterious charms, its otherworldly sounds and whispers that lead to dreaming and sadness, impressed Fuchs to the point of stepping – ecstatically – on the piano pedals three hours, but without playing, for fear of disturbing that peaceful night; he reached by this weird means of locomotion a darkened district where a mysterious power attracted him against his will, and as the town gossips say, precisely on the famous street which the good emperor Trajan, following Nerva’s, his father’s counsel, pointed out to Bucur, the sheep herder, to lay out among the first in the town which bears his name…

Suddenly a good number of the earthly votaries of Venus, humble servants, all of them, at love’s altar, all dressed in transparent whites, their lips the color of burgundy and their eyes shaded, surrounded Fuchs on all sides… It was a superb summer night. Songs and gaiety, sweet whispers and melodies all around… The vestals of pleasure welcomed the artist with flowers, artfully embroidered napkins, curious cans and antique vessels brimming with fragrances. They were shouting and they were trying to outdo each other: “Dearest Fuchs, let me have your immaterial love!” “Oh, Fuchs, you are the only one who can love us in purity!”; then, as if urged by one and the same thought, they ended up chanting in unison “Dear Fuchs, do play a sonata!”…

Fuchs slipped shyly inside the piano. All efforts to make him come out were in vain. The artist relented to allow just his hands pulled outside, then gave magisterial performances of one dozen concertos, fantasias, etudes and sonatas; for three continuous hours he played scale as well as all sorts of exercises for “legato,” “staccato,” and “Schule der Geläufigkeit”…

The Goddess Venus herself, Venus born of the white foam of the sea was enchanted, very likely and especially by the “legato” studies the sonorities of which reached her on mount Olympus and disturbed Venus’ quiet (Venus who had not been anybody’s since Vulcan and Adonis) who now sinned in her mind and, defeated by passion and unable to resist the temptation in the hearing of Fuchs, made up her mint to have him for the night…

With this end in mind, she sent Cupid to shoot an arrow into his heart – the arrow point carrying a little note inviting him to Olympus.

III

The Three Graces appeared at the appointed hour…

They picked Fuchs up and carried him lightly on soft, voluptuous arms all the way to a silk ladder made from music staffs, a ladder hanging from the balcony of Olympus where Venus was expecting him…

It so happened however, Vulcan-Hephaistos caught on to everything and saw to it that Zeus would send a downpour by way of revenge…

Fuchs, on the other hand, his umbrella out to be repaired, would not admit defeat; since he knew how to move in and around staffs with the greatest ease, and aided as he was by the strong gusts of his composer’s inspiration, he kept moving higher, braving the elements of nature. He finally made it, soaked to Olympus. Aphrodite gave him a hero’s welcome. She embraced him, she kissed him passionately, then she sent him to a prune drying plant.

When night came, Fuchs was ushered into the alcove. Around him there were only flowers and song. The Graces and the other Olympian attendants of Venus went dancing before him covering with flowers and sprinkling heady scents on him, as little cupids in the distance, under the divine baton of Orpheus, were intoning songs in praise of love…

The Nine Muses showed up next. In Euterpe’s melodious voice they called out this greeting to Fuchs:

“Welcome, chosen mortal; your art brings men closer to the Gods! Venus is expecting you! May Jupiter make your art and love worthy of the Goddess – our mistress, and may a new and superior seed arise from the love that unites you, the seed that will people not just the earth which can only aspire to Olympus, but Olympus too, which is so like the Earth in being subject to decadence!...”

Said they, and the little invisible cupids intoned the praises of love once more, as the rhapsodes of Olympus exalted that immortal moment to high heaven on their lyres.

Before long everything became silent again… There was nobody around any more… There was a bluish sort of half-light in the alcove. Venus was naked: she was light-skinned, her hands raised behind her head and joined under her unbraided golden hair in a gesture of delicious abandon and intense voluptuousness she stretched her superb milky body on the bed of soft cushions and flowers. All was warmth and provocative fragrances. Out of modesty and fear, Fuchs would have wished to get inside some crack. But since there is no such thing on Olympus, he realized that he had to make himself bold.

He felt the urge to run around the room a little, but Aphrodite of the fine hands saved him from his quandary with her rose-scented fingers… She picked him up gingerly, she caressed him, she lifted him two or three times to the ceiling and after giving him a long soulful look, she kissed him passionately. She caressed him some more, then she kissed him hundreds of times and placed him lightly between her breasts…

Fuchs started to shake with joy at the same time that fear made him want to jump down somewhere like a flea. But because those warm and fragrant breasts had made him dizzy and confused, he took to running all over, like some tadpole at its wits’ end, traveling in a zig-zag line on the Goddess’s body, twitch-fast, passing like a madman over the pink tips of the breasts, over the silky shoulders, squeezing between her hot and curvy legs…

Fuchs was changed beyond recognition. His glasses cast kinky reflexions, his moustache was libidinous and lubricious. Quite some time went by in this manner, but the artist did not have the foggiest idea what was still left for him to do, nor could the Goddess wait very much longer.

He had heard somewhere “In love, as opposed to music, all ends with overture.” Oh, well, Fuchs could neither find… not hear it anywhere…

Suddenly it dawned on him that just as Overture, in music, may refer to nothing but the ear, what with the ear being the noblest Overture of the body (among those known to Fuchs) – organ of divine music and also the way by which he, coming into the world, saw the light of day for the first time – supreme happiness could be found nowhere but in the ear…

Fuchs perked up, gathered strength, tensed up, and rushed, in a “sforzando,” at an unspeakable, frantic speed to penetrate and to push through the little ear-hole on the right ear-lobe of the Goddess, close by the spot where she inserted her earrings; he completely disappeared inside.

The joint choirs of the little invisible cupids and muses sang the praises of love once more in the distance, and once more the rhapsodes of Olympus exalted, with inspiration, the immortal moment to high heaven on their lyres…

After an hour’s stay, during which time he checked his fig leaf and sketched a romance for the piano, Fuchs showed up, finally, on the ear-lobe, in tails and white tie, radiant, satisfied, thanking and congratulating the crowds, right and left, which had waited in the cold, precisely as he knew he should behave on Earth whenever he gave a gala concert. He stepped forward and offered Venus the romance he had dedicated to her.

But to his surprise and dismay the artist discovered that not one round of applause came from anywhere. As a matter of fact, all the inhabitants of Olympus were staring at each other in confusion. Amazed, at first, to see that Fuchs considered his task fully executed, feeling, then, opposed and gravely offended, she who had not suffered a similar affront from Zeus, got to her feet and red with anger shook her head, gracefully yet powerfully enough to make Fuchs fall down to Earth.

Suddenly, as if obeying an invisible signal, all Olympus was up in a roar… Shouts and threats rained all about. Everybody was livid at the insult that clumsy mortal had leveled at Olympus… One powerful hand, following the orders of Apollo and Mars, yanked Fuchs’ fig leaf out, then tacked on the things to which he was really entitled. A stiff ordinance was passed that fig leaves from then on, would indeed be awarded, but only to statues… A delicate hand, in the meantime, actually the Goddess’s rosy-fingered hand, picked the artist by one ear and, with one noble motion, threw him out into Chaos.

IV

A deluge of catcalls and threats. A deluge of dissonant sounds, chords reversed and unresolved, cadences eluded, false relations, trills and, above all, rests, rained over the hounded artist. A hailstorm of sharps and sharp naturals hit him on the back; one somewhat long rest shattered his glasses… Other, meaner, Gods threw Roman trumpets, Aeolian harps, lyres and cymbals at him, the peak of vengeance pouring down in the form of “Actaeon,” “Polyeucte,” and Enesco’s IIIrd Symphony, their music, this time, literally, descending from Olympus.

Fuchs’ fate had been decided. He first had to wander through Chaos at a fantastic speed, in five minute circles around the planet Venus, then, to expiate his affront to the Goddess, he would be exiled all by himself on the uninhabited planet with the obligation of delivering himself, all by his own means, of his own progeny, that superior breed of artists which he would leave there and which ought to have sprung forth on Olympus out of his love for Venus.

Fuchs had already started on his penance when the tender-hearted Pallas Athene (unexpectedly) intervened on his behalf…

He was allowed to drop back to Earth, but on one condition: there being enough useless progeny around, artistic or otherwise, there was no need for a new one to be created… Fuchs was charged, however, to wipe out snobbery and intellectual cowardice from the arts of the Earth.

Faced with a terrible dilemma, and after long and mature pondering, the artist decided that his latter condition was harder to fulfill than the one requiring that he create progeny on the planet Venus…

It was a valiant decision that the hero took then as he wandered through Chaos. He declared that he accepted Athene’s favor, condition and all; but when he sensed that he was getting nearer to the Earth, by somehow moving a bit to the right, he dropped in the very same red-light district he felt an attraction for and where he had originally left from.

This time thinking himself well prepared to learn and to practice there all those things he did not till then know, and so he could, later on, ask Venus for an audience and a chance to reinstate himself over those points that he had left so very much to be desired. This way, he told himself, the creation of the new breed of super-men would be possible, and this way, too, the accomplishing of the impossible task he had to perform on earth would come to pass.

But the handmaidens of pleasure who received him with smiles, upon finding out what his intentions were this time around, surrounded him, brusquely stopped him from going any further, and feeling themselves slighted and angered, shaking their fists in the air in protest, excommunicated him from the district shouting all at the same time:

“Alas, Fuchs, we’ve lost you and can barely recognize you, for you were once upon a time the only man since Plato who still knew how to love innocently… How can you bear to came and walk in our midst! Woe to us from now on, doing without the aesthetic experience of your sonatas; woe to you, doing without the inspiration our elevated love could give you! Shame on her who, although our mistress, Mount Olympus’ and the world’s, was incapable of understanding you and, by refusing both your love and your art, caused you to fall so high! Go away, Fuchs, for you are not worthy of us.”

“Go away, Fuchs, you dirty satyr! How could you not respect the noblest organ, the ear?! Go away, Fuchs, you are giving our district a bad name.”

“Go away, Fuchs, and may the Gods protect you!”

Excommunicated, and fearing an eventual discharge of wet anger from them, Fuchs sat hurriedly at the piano and pedaling energetically and uninterruptedly, arrived finally at his quiet home, depressed, disconcerted, disgusted with mankind and with the Gods, love, and the Muses…

He ran to take his umbrella from the repair shop and, taking his piano along, went out of sight in the bosom of the great and boundless nature…

From that spot music has been beaming away with equal force in all direction, fulfilling thus, in part, the utterance of grateful Destiny which had ordained him to spread that utterance far and wide through the aid of his scales, concerts, and staccato etudes, and through the power of education, to bring about the appearance of a better and superior race of men, to the greatest glory of himself, the piano, and of Eternity…

English version by Stavros DELIGIORGIS

Ismail And Turnavitu

by Urmuz (Dem. Dumitrescu-Buzău) (1883-1923)

Ismaïl is made up of eyes, sideburns, and a dress, and can be found with the greatest difficulty these days.

Time was when Ismaïl grew in botanical gardens as well, but then, more recently and thanks to the advances of modern science, one has been synthesized chemically.

Ismaïl never walks all by himself. He may be seen about 5:30 early in the morning, walking in a zig-zag line on Arioanoaia street, in the company of a badger to which he is leashed by a streamer cable and which he eats raw after he was ripped its ears off and squeezed some lemon on… Ismaïl raises badgers in a seed-bed in the bottom of a hole in Dobrodgea until they are 16 years old and have grown fuller; then, shielded from every kind of penal responsibility, he sets upon dishonoring them, one after another, without the smallest qualm of conscience.

For the greatest part of every year no one knows where Ismaïl lives. It is believed that he spends his time preserved inside a jar in the attic of his dear father’s house, his father being a nice old man, his nose pulled through a press and surrounded by a fence made of twigs. He keeps Ismaïl thus sequestered, it is said, so he will not be stung by bees or be reached by the corruption of our electoral mores. Still Ismaïl manages to get away during the three winter months of every year when it is his greatest pleasure to don a gala dress made of quilted bedding with large brick-red flowers, climb on the beams of various duplexes on national Putty Day with the sole purpose of being offered by the owners to the workers to share and thus, hopefully, contribute to a significant extent to a solution of the labor issue… Ismaïl gives audiences too but only on top of the hill near the badger seed bed. Hundreds of job applicants, grants-in-aid, and firewood are first stuck under an enormous lampshade where they have to hatch four eggs each. They are then loaded into town-hall garbage carts and carried with breathtaking speed up to Ismaïl by a certain friend of his who also helps him to a salami called Turnavitu, a strange character who at the time of the ascent has the bad habit of asking the job applicants to promise they’ll send him love letters, upon threat of overturning them.

Turnavitu for a long time was but a simple air fan in the various dirty Greek coffee houses on Covaci and Gabroveni streets. Unable to stand the odor he was forced to breathe in those places, Turnavitu, went into politics for a long stretch of time and succeeded in being named a fan of the FederalState at the Radu Vodă fire department kitchens.

He met Ismaïl at an evening dancing party. Laying out before him the terrible state he was in on account of his frequent gyrations, soft-hearted Ismaïl took him under his wing. Turnavitu was promised to begin getting 50 cents daily plus a per diem, his only obligation being to serve as Ismaïl’s chamberlain at the badgers’ place; likewise to appear before him every morning on Arionoaia street and to step on the badger’s tail only to make profuse apologies for his carelessness, compliment Ismaïl on his dress by swabbing rape oil on him with a pompom, and wish him success and happiness…

That his friend might like him better still, Turnavitu would take, once a year, the form of a jerry-can; if he was filled with gas to the top he would take a long trip customarily to Majorca and Minorca; most of these trips consisting of a going, the hanging of a lizard on the Port Captain’s doorknob, and the return home…

On the way back from one of these trips Turnavitu contracted such an unsufferable case of the common cold which he passed on to the badgers that, because of their endless sneezing, Ismaïl couldn’t have them at his beck and call any more. Turnavitu was instantly fired from the job.

A being uncommonly sensitive and incapable of tolerating this kind of humiliation, Turnavitu began setting his macabre suicide plan in motion, but not before seeing tot the extraction of the four canines in his mouth.

Before passing on, he took his terrible revenge on Ismaïl by having all of his dresses stolen, pouring gas over them out of himself, and setting fire to them in a vacant lot. Reduced to the depressed state of being just eyes and sideburn, Ismaïl could just scarcely creep to the edge of the seed-bed with the badgers where he went into decrepitude and has remained so to this very day…

English version by Stavros DELIGIORGIS

The versions signed by Stavros DELIGIORGIS taken from Urmuz, Pagini Bizare. Weird Pages,

Ed. Cartea Românească, 1985

Urmuz este artistul care s-a sinucis fara niciun temei, doar din dorinta de a demonstra ca a-ti lua viata nu este decat unul din actele banale ale existentei in aceasta lume. Iar demonstraia i-a reusit de minune. Nici macar nu a facut-o pentru a atrage atentia asupra operei sale, asa cum s-a mai intamplat cu alii, pe alte meleaguri. Nu s-a sinucis nici dezamagit in amor, obicei indeobste cunoscut si la noi, si la altii, practicat si de cei cu putina instructie, dar si de nume mari ale literaturii. Fara indoiala, gestul sau se cere luat ca atare. Nu are nimic straniu, nu este nimic de neinteles. Moartea vine si gratis, si atunci cand o chemi.

De mic s-a aratat pasionat de lectura, firesc, de literatura de aventuri, cea de calatorii, mai ales cea privind voiaje imaginare si extraordinare, atat de gustata la inceputul veacului al XX-lea. Aceste lecturi si dezvolta imaginatia, pasiunea pentru asociatii inedite, in discursuri perfecte din punct de vedere gramatical si stilistic. Logica este insa scurt-circuitata, ceea ce nu se intampla in romanele astronomice, prototipul celor science-fiction de mai tarziu, si unde respectul pentru aparenta rigoare logica si stiintifica era pastrat cu mare atentie.

Pseudonimul de Urmuz i-a fost dat de Tudor Arghezi.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu