“Murakami is like a magician who explains what he’s doing as he performs the trick and still makes you believe he has supernatural powers . . . But while anyone can tell a story that resembles a dream, it's the rare artist, like this one, who can make us feel that we are dreaming it ourselves.” —The New York Times Book Review

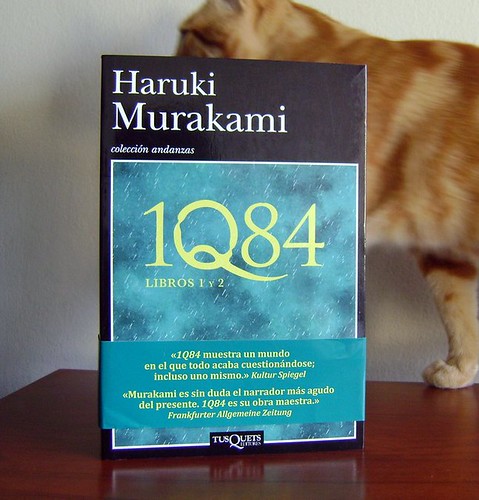

The year is 1984 and the city is Tokyo.

A young woman named Aomame follows a taxi driver’s enigmatic suggestion and begins to notice puzzling discrepancies in the world around her. She has entered, she realizes, a parallel existence, which she calls 1Q84 —“Q is for ‘question mark.’ A world that bears a question.” Meanwhile, an aspiring writer named Tengo takes on a suspect ghostwriting project. He becomes so wrapped up with the work and its unusual author that, soon, his previously placid life begins to come unraveled.

As Aomame’s and Tengo’s narratives converge over the course of this single year, we learn of the profound and tangled connections that bind them ever closer: a beautiful, dyslexic teenage girl with a unique vision; a mysterious religious cult that instigated a shoot-out with the metropolitan police; a reclusive, wealthy dowager who runs a shelter for abused women; a hideously ugly private investigator; a mild-mannered yet ruthlessly efficient bodyguard; and a peculiarly insistent television-fee collector.

Un roman cu un titlu provocator, 1Q84 (în japoneză, cifra nouă se pronunţă „qew“), şi un scriitor care face vîlvă pe trei continente, Haruki Murakami – o ecuaţie al cărei rezultat este bestsellerul. Cînd a apărut în Japonia, în 2009, 1Q84 (roman în trei volume, dintre care la noi au fost publicate primele două, al treilea fiind în curs de traducere la Editura Polirom, în seria de autor „Haruki Murakami“) a vîndut peste o sută de mii de exemplare numai în prima săptămînă şi, de atunci, a ajuns deja la un milion. În întreaga lume, fanii au aşteptat cu nerăbdare ca editurile să se angajeze în curajosul proiect al publicării a peste o mie de pagini de literatură pură – am ales termenul „curajos“, întrucît, într-o societate în care totul pare livrat în „rezumat“, o mie de pagini înseamnă cu adevărat o provocare, pe care mulţi nu sînt dispuşi să şi-o asume, atît ca editori, cît şi ca cititori. Dar Murakami nu este un debutant, iar a miza pe el duce aproape cu certitudine la succes. Aşa că, la fel cum se întîmplă, de pildă, în cazul unui Rushdie, o mie de pagini ale lui Murakami sînt citite pe nerăsuflate şi, în aşteptarea lor, blogurile fanilor s-au umplut de comentarii şi de speculaţii cu privire la noul roman, unii încercînd chiar să traducă fragmente, pentru a surprinde ceva din acţiune şi din atmosferă. Dar, pînă la apariţia traducerilor, singurul element important din noul său roman care a reuşit să transpară a fost că, şi de această dată, un rol semnificativ îl joacă muzica: chiar din primul rînd, se vorbeşte despre Sinfonietta lui Janácek (compusă în 1926 şi dedicată eliberării Cehoslovaciei), compoziţie ce reprezintă nu numai, aşa cum se va constata, un punct de legătură între cele două personaje principale ale cărţii, Tengo şi Aomame, ci este semnificativă şi pentru construcţia narativă: o alternare între „allegretto“ şi „andante“, cu secvenţe „moderato“ la mijloc.

Cît de importantă este povestea pentru omul contemporan

Din fericire, scriitorul japonez nu s-a complăcut în postura conferită de reuşitele sale anterioare şi se dovedeşte în continuare un prozator în permanentă căutare de noi provocări, de noi formule literare, de mijloace inedite de expresie. Evident, este o naraţiune în care regăsim elemente-cheie ale scriiturii lui Murakami: 1Q84 este o poveste presărată cu nenumărate aluzii la cultura europeană, de pildă Cehov şi principiul „dacă în primul act există un pistol, atunci, în ultimul act, cineva va trebui să tragă cu el“,Alice în Ţara Minunilor, Sinfonietta lui Janácek, Rolling Stones, filmul Lovitura, cu Steve McQueen – toate acestea pe fundalul unei Japonii moderne, al unei capitale, Tokio, aglomerate, nepăsătoare, agitate şi, într-o oarecare măsură, mecanice, asemenea oricărei metropole din lume. Murakami rămîne eternul îndrăgostit nu numai de marea bogăţie a culturii europene şi americane (e suficient de precizat că şi-a intitulat cărţi anterioare după melodii de Nat King Cole sau Beatles), ci şi de tot ceea ce înseamnă potenţial imaginativ şi explorare a tuturor colţurilor creativităţii. Pentru Murakami, fiecare carte este – şi comparaţia cu Rushdie mi se pare din nou pertinentă – un nou prilej de a vedea ce lumi fascinante mai poate clădi imaginaţia şi de a arăta cît de importantă este povestea pentru omul contemporan.

1Q84 are o construcţie narativă aşa cum întîlnim de obicei la Murakami: neliniară, dar de data aceasta doar pe două planuri, fără poveşti auxiliare care să complice intriga: unul în care apare Aomame, o femeie de treizeci de ani care, printr-o tehnică stăpînită la perfecţiune, îi omoară pe bărbaţii ce se găsesc vinovaţi de ceva grav, şi altul în care Tengo, profesor de matematică, dar şi un scriitor talentat, acceptă să îi ajusteze stilistic cartea lui Fukaeri, o adolescentă de şaptesprezece ani, dislexică, dar care se anunţă a fi noua senzaţie a debuturilor literare, cu o poveste despre nişte Oameni Mici, care ţes crisalide de aer. Deşi nu se întîlnesc decît o dată pe tot parcursul acţiunii, atunci cînd au zece ani, Tengo şi Aomame alcătuiesc cea mai frumoasă poveste de dragoste întîlnită în cărţile lui Murakami: se iubesc fără să ştie că şi celălalt simte la fel, fiecare reprezintă pentru celălalt un punct esenţial al existenţei. Se uită amîndoi la cerul pe care strălucesc două luni şi se caută fără ca măcar ei înşişi să ştie de ce. Evident că nu se pot întîlni, pentru că Aomame vine din anul 1984, iar lumea lui Tengo este a anului 1Q84 şi, chiar atunci cînd Aomame trece graniţa celor două spaţii, este doar pentru a afla că numai dacă ea moare, Tengo va putea să trăiască.

O realitate în care totalitarismul apare reflectat din interior

Cu un titlu care face destul de evident trimitere la Orwell, 1Q84 este totuşi o carte în care cititorii nu vor regăsi foarte multe din 1984: Murakami nu construieşte o lume totalitară, în care oamenii sînt urmăriţi permanent de ochiul atotştiutor al unui „frate mai mare“, ci o realitate în care totalitarismul apare reflectat din interior, nefiind dictat de o instanţă exterioară. Big Brother este înlocuit de Oamenii cei Mici, şi nici măcar aceştia nu sînt pe post de stăpîni absoluţi. Oamenii cei Mici sînt monştrii în care indivizii se pot transforma cu uşurinţă atunci cînd se lasă pradă ideilor fixe. Oamenii cei Mici, personaje în cartea unei adolescente de şaptesprezece ani, Fukaeri, capătă formă în cadrul unei grupări, Pionierii, iniţial o mişcare religioasă paşnică, avînd o doctrină austeră, dar care ajunge să comită atrocităţi, în numele unui principiu divin călăuzitor (povestea este o reflectare a unei situaţii reale: grupul religios Aum Shinrikyo, fondat în anul 1984 şi care, în 1995, a iniţiat atacuri teroriste cu gaz sarin, răspîndit în reţeaua de metrou din Tokio).

„Mi-e teamă că mare parte din creativitatea noastră o să rămînă captivă în noi, în propriile noastre universuri, ceea ce ar face ca lumea noastră să fie cu adevărat lumea imaginată de Orwell, în 1984“, afirma Murakami într-un interviu din Yomiuri Shimbun, în 2009. O lume care nu ar mai vedea frumuseţea pe care o are de oferit arta, sub orice formă ar fi ea, ar putea într-adevăr să alunece într-un pustiu al imaginaţiei, din care se plămădesc forme monstruoase: la Murakami, nu mai există Big Brother-ul lui Orwell, ci apar Oamenii cei Mici, iar creatorul lor este… fanatismul. Nu e prima oară cînd Murakami inserează aspecte ale realităţii imediate în scrierile sale. De altfel, este o notă specifică prozei lui să vorbească despre lucruri incomode: droguri, prostituţie, lipsă de comunicare reală, psihoze, traume, tendinţe sinucigaşe, poveşti de dragoste care nu se termină cu happy end, abuzuri – sexuale sau psihice etc. Iată un fragment din 1Q84 ce prezintă întreaga gamă de antieroi ai cărţii: „Un bărbat căruia îi face plăcere să violeze fete care încă nu au ciclu, un bodyguard homosexual musculos, o tînără însărcinată în şase luni care se sinucide cu somnifere, o femeie care omoară bărbaţi problematici înţepîndu-i cu un ac ascuţit în ceafă…“. Şi totuşi, nu te izbesc cu duritatea de tip reality-show, adesea întîlnită în scriitura contemporană, şi asta pentru că, oricît de verosimile ar fi aceste personaje sau situaţii, ele nu cad niciodată în trivial, există întotdeauna o notă de poetic şi, de ce nu, de fantastic, care trimite nu atît la ceva imposibil, ci, dimpotrivă, la ceva ce poate, cîndva, s-ar putea întîmpla. Este o lume ce cuprinde personaje asemenea celor descrise mai sus, dar, în acelaşi timp, este un spaţiu luminat de două luni, pe care nu oricine le poate vedea, o lume în care există monştri, dar şi crisalide de aer, ce pot conţine speranţa unui nou început. Murakami este un rar exemplu de scriitor care ştie să aleagă inspirat aspecte din realitatea înconjurătoare şi să le dea forma potrivită pentru ca acestea să devină literatură.

Cred că pînă şi un iubitor al literaturii neangajate, al „artei pentru artă“ ar aprecia stilul lui Murakami. Mai ales în acest ultim roman al său, care oferă posibilitatea a cel puţin două interpretări: îl poţi citi strict livresc, ca pe un metaroman (în care un plan este cel al autorului, iar celălalt, al poveştii create de el şi care capătă atîta coerenţă şi independenţă, încît nici autorul nu mai ştie dacă deţine controlul sau dacă el însuşi devine parte a ficţiunii), sau ca pe o poveste pe două planuri, în care personajele, deşi trec din 1984 într-un an 1Q84, un timp al tuturor posibilităţilor, sînt reprezentative pentru lumea secolului al XXI-lea. Cu toate că nu filonul realist este cel definitoriu pentru proza lui Murakami, se poate vorbi despre o mutaţie în ceea ce priveşte receptarea scrierilor sale, mutaţie despre care el însuşi vorbeşte în interviul citat mai sus: în lumea post-9/11, care a făcut ca raportul realitate-ficţiune să se răstoarne, în sensul că evenimentele, prin oroarea lor, au părut a fi nu brutal de reale, ci dimpotrivă, suprareale, genul de scriere practicată de Murakami a început să fie acceptat drept un soi de nou realism.

În 1Q84, tot ceea ce este specific lui Murakami este şlefuit, adus la o claritate şi, în acelaşi timp, la o profunzime pe care nu le-am întîlnit în nici unul dintre celelalte romane ale sale. Naraţiunea (scriitorul adoptă pentru prima oară persoana a treia) este, aşa cum îi place lui Murakami, fragmentată, dar nu într-atît încît lectura să devină greoaie, aşa cum se întîmplă în Cronica păsării-arc, de pildă. 1Q84 este romanul total, aşa cum spera Murakami să ajungă să creeze, romanul capodoperă, în care toate episoadele sînt mici bijuterii stilistice şi de construcţie narativă.

The Fierce Imagination of Haruki Murakami

By SAM ANDERSON

I prepared for my first-ever trip to Japan, this summer, almost entirely by immersing myself in the work of Haruki Murakami. This turned out to be a horrible idea. Under the influence of Murakami, I arrived in Tokyo expecting Barcelona or Paris or Berlin — a cosmopolitan world capital whose straight-talking citizens were fluent not only in English but also in all the nooks and crannies of Western culture: jazz, theater, literature, sitcoms, film noir, opera, rock ’n’ roll. But this, as really anyone else in the world could have told you, is not what Japan is like at all. Japan — real, actual, visitable Japan — turned out to be intensely, inflexibly, unapologetically Japanese.

This lesson hit me, appropriately, underground. On my first morning in Tokyo, on the way to Murakami’s office, I descended into the subway with total confidence, wearing a freshly ironed shirt — and then immediately became terribly lost and could find no English speakers to help me, and eventually (having missed trains and bought lavishly expensive wrong tickets and gestured furiously at terrified commuters) I ended up surfacing somewhere in the middle of the city, already extremely late for my interview, and then proceeded to wander aimlessly, desperately, in every wrong direction at once (there are few street signs, it turns out, in Tokyo) until finally Murakami’s assistant Yuki had to come and find me, sitting on a bench in front of a honeycombed-glass pyramid that looked, in my time of despair, like the sinister temple of some death-cult of total efficiency.

And so I was baptized by Tokyo’s underground. I had always assumed — naively, Americanly — that Murakami was a faithful representative of modern Japanese culture, at least in his more realist moods. It became clear to me down there, however, that he is different from the writer I thought he was, and Japan is a different place — and the relationship between the two is far more complicated than I ever could have guessed from the safe distance of translation.

One protagonist of Murakami’s new novel, “1Q84,” is tormented by his first memory to such an extent that he makes a point of asking everyone he meets about their own. When I met Murakami, finally, in his Tokyo office, I made a point of asking him what his own first memory was. When he was 3, he told me, he managed somehow to walk out the front door of his house all by himself. He tottered across the road, then fell into a creek. The water swept him downstream toward a dark and terrible tunnel. Just as he was about to enter it, however, his mother reached down and saved him. “I remember it very clearly,” he said. “The coldness of the water and the darkness of the tunnel — the shape of that darkness. It’s scary. I think that’s why I’m attracted to darkness.” As Murakami described this memory, I felt a strange internal joggling that I couldn’t quite place — it felt like déjà vu crossed with the spiritual equivalent of having to sneeze. It struck me that I had heard this memory before, or, eerily, that I was somehow remembering the memory myself, firsthand. Only much later did I realize that I was, indeed, remembering the memory: Murakami had transferred it to one of his very minor characters near the beginning of “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle.”

That first visit to Murakami took place on a muggy midmorning, midweek, in the middle of an impossibly difficult summer for Japan — a summer spent trying to deal, here in reality, with the aftermath of a seemingly unreal disaster. The tsunami hit the northern coast four months before, killing 20,000 people, destroying entire towns, causing a partial nuclear meltdown and plunging the country into a handful of simultaneous crises: energy, public health, media, politics. (When the prime minister stepped down recently, it made him the fifth in five years to do so.) I had come to speak with Murakami, Japan’s leading novelist, about the translation into English (and also French, Thai, Spanish, Hebrew, Latvian, Turkish, German, Portuguese, Swedish, Czech, Russian and Catalan) of his massive “1Q84” — a book that has already sold millions of copies across Asia and generated serious Nobel Prize chatter in most of the languages in which it is not yet even available. At age 62, three decades into his career, Murakami has established himself as the unofficial laureate of Japan — arguably its chief imaginative ambassador, in any medium, to the world: the primary source, for many millions of readers, of the texture and shape of his native country.

This, no doubt, comes as an enormous surprise to everyone involved.

Murakami has always considered himself an outsider in his own country. He was born into one of the strangest sociopolitical environments in history: Kyoto in 1949 — the former imperial capital of Japan in the middle of America’s postwar occupation. “It would be difficult to find another cross-cultural moment,” the historian John W. Dower has written of late-1940s Japan, “more intense, unpredictable, ambiguous, confusing, and electric than this one.” Substitute “fiction” for “moment” in that sentence and you have a perfect description of Murakami’s work. The basic structure of his stories — ordinary life lodged between incompatible worlds — is also the basic structure of his first life experience.

Murakami grew up, mostly, in the suburbs surrounding Kobe, an international port defined by the din of many languages. As a teenager, he immersed himself in American culture, especially hard-boiled detective novels and jazz. He internalized their attitude of cool rebellion, and in his early 20s, instead of joining the ranks of a large corporation, Murakami grew out his hair and his beard, married against his parents’ wishes, took out a loan and opened a jazz club in Tokyo called Peter Cat. He spent nearly 10 years absorbed in the day-to-day operations of the club: sweeping up, listening to music, making sandwiches and mixing drinks deep into the night.

His career as a writer began in classic Murakami style: out of nowhere, in the most ordinary possible setting, a mystical truth suddenly descended upon him and changed his life forever. Murakami, age 29, was sitting in the outfield at his local baseball stadium, drinking a beer, when a batter — an American transplant named Dave Hilton — hit a double. It was a normal-enough play, but as the ball flew through the air, an epiphany struck Murakami. He realized, suddenly, that he could write a novel. He had never felt a serious desire to do so before, but now it was overwhelming. And so he did: after the game, he went to a bookstore, bought a pen and some paper and over the next couple of months produced “Hear the Wind Sing,” a slim, elliptical tale of a nameless 21-year-old narrator, his friend called the Rat and a four-fingered woman. Nothing much happens, but the Murakami voice is there from the start: a strange broth of ennui and exoticism. In just 130 pages, the book manages to reference a thorough cross-section of Western culture: “Lassie,” “The Mickey Mouse Club,” “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” “California Girls,” Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto, the French director Roger Vadim, Bob Dylan, Marvin Gaye, Elvis Presley, the cartoon bird Woodstock, Sam Peckinpah and Peter, Paul and Mary. That’s just a partial list, and the book contains (at least in its English translation) not a single reference to a work of Japanese art in any medium. This tendency in Murakami’s work rankles some Japanese critics to this day.

Murakami submitted “Hear the Wind Sing” for a prestigious new writers’ prize and won. After another year and another novel — this one featuring a possibly sentient pinball machine — Murakami sold his jazz club in order to devote himself, full time, to writing.

“Full time,” for Murakami, means something different from what it does for most people. For 30 years now, he has lived a monkishly regimented life, each facet of which has been precisely engineered to help him produce his work. He runs or swims long distances almost every day, eats a healthful diet, goes to bed around 9 p.m. and wakes up, without an alarm, around 4 a.m. — at which point he goes straight to his desk for five to six hours of concentrated writing. (Sometimes he wakes up as early as 2.) He thinks of his office, he told me, as a place of confinement — “but voluntary confinement, happy confinement.”

“Concentration is one of the happiest things in my life,” he said. “If you cannot concentrate, you are not so happy. I’m not a fast thinker, but once I am interested in something, I am doing it for many years. I don’t get bored. I’m kind of a big kettle. It takes time to get boiled, but then I’m always hot.”

That daily boiling has produced, over time, one of the world’s most distinctive bodies of work: three decades of addictive weirdness that falls into an oddly fascinating hole between genres (sci-fi, fantasy, realist, hard-boiled) and cultures (Japan, America), a hole that no writer has ever explored before, or at least nowhere near this deep. Over the years, Murakami’s novels have tended to grow longer and more serious — the sitcom references have given way, for the most part, to symphonies — and now, after a particularly furious and sustained boil, he has produced his longest, strangest, most serious book yet.

Murakami speaks excellent English in a slow, deep voice. He dislikes, he told me, speaking through a translator. His accent is strong — inflections would rise dramatically or drop off suddenly just when I was expecting them to hold steady — and yet only rarely did we have trouble understanding each other. Certain colloquialisms (“I guess”; “like that”) cycled in and out of his speech in slightly odd positions. I got the sense that he enjoyed being out of his linguistic element: there’s a touch of improvisational fun in his English. We sat at a table in his office in Tokyo, the headquarters of what he refers to half-jokingly as Murakami Industries. A small staff buzzed around, shoelessly, in the other rooms. Murakami wore blue shorts and a short-sleeve button-up shirt that appeared to have been — like many of his characters’ shirts — recently ironed. (He loves ironing.) He was barefoot. He drank black coffee out of a mug featuring the Penguin cover of Raymond Chandler’s “Big Sleep” — one of his first literary loves, and a novel he is currently translating into Japanese.

As we began to talk, I set my advance copy of “1Q84” on the table between us. Murakami seemed genuinely alarmed. The book is 932 pages long and nearly a foot tall — the size of an extremely serious piece of legislation.

“It’s so big,” Murakami said. “It’s like a telephone directory.”

This, apparently, was Murakami’s first look at the American version of the book, which, as tends to happen in such cultural exchanges, has been slightly denatured. In Japan, “1Q84” came out in three separate volumes over two years. (Murakami originally ended the novel after Book 2 and then decided, a year later, to add several hundred more pages.) In America, it has been supersized into a single-volume monolith and positioned as the literary event of the fall. You can watch a fancy book trailer for it on YouTube, and some bookstores are planning to stay open until midnight on its release date, Oct. 25. Knopf was in such a hurry to get the book into English that they split the job between two translators, each of whom worked on separate parts.

I asked Murakami if he intended to write such a big book. He said no: that if he’d known how long it would turn out to be, he might not have started at all. He tends to begin a piece of fiction with only a title or an opening image (in this case he had both) and then just sits at his desk, morning after morning, improvising until it’s done. “1Q84,” he said, held him prisoner for three years.

This giant book, however, grew from the tiniest of seeds. According to Murakami, “1Q84” is just an amplification of one of his most popular short stories, “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning,” which (in its English version) is five pages long. “Basically, it’s the same,” he told me. “A boy meets a girl. They have separated and are looking for each other. It’s a simple story. I just made it long.”

“1Q84” is not, actually, a simple story. Its plot may not even be fully summarizable — at least not in the space of a magazine article, written in human language, on this astral plane. It begins at a dead stop: a young woman named Aomame (it means “green peas”) is stuck in a taxi, in a traffic jam, on one of the elevated highways that circle the outskirts of Tokyo. A song comes over the taxi’s radio: a classical piece called the “Sinfonietta,” by the Czechoslovakian composer Leos Janacek — “probably not the ideal music,” Murakami writes, “to hear in a taxi caught in traffic.” And yet it resonates with her on some mysterious level. As the “Sinfonietta” plays and the taxi idles, the driver finally suggests to Aomame an unusual escape route. The elevated highways, he tells her, are studded with emergency pullouts; in fact, there happens to be one just ahead. These pullouts, he says, have secret stairways to the street that most people aren’t aware of. If she is truly desperate she could probably manage to climb down one of these. As Aomame considers this, the driver suddenly issues a very Murakami warning. “Please remember,” he says, “things are not what they seem.” If she goes down, he warns, her world might suddenly change forever.

She does, and it does. The world Aomame descends into has a subtly different history, and there are also — less subtly — two moons. (The appointment she’s late for, by the way, turns out to be an assassination.) There is also a tribe of magical beings called the Little People who emerge, one evening, from the mouth of a dead, blind goat (long story), expand themselves from the size of a tadpole to the size of a prairie dog and then, while chanting “ho ho” in unison, start plucking white translucent threads out of the air in order to weave a big peanut-shaped orb called an “air chrysalis.” This is pretty much the baseline of craziness in “1Q84.” About halfway through, the book launches itself to such rarefied supernatural heights (a levitating clock, mystical sex-paralysis) that I found myself drawing exclamation points all over the margins.

For decades now, Murakami has been talking about working himself up to write what he calls a “comprehensive novel” — something on the scale of “The Brothers Karamazov,” one of his artistic touchstones. (He has read the book four times.) This seems to be what he has attempted with “1Q84”: a grand, third-person, all-encompassing meganovel. It is a book full of anger and violence and disaster and weird sex and strange new realities, a book that seems to want to hold all of Japan inside of it — a book that, even despite its occasional awkwardness (or maybe even because of that awkwardness), makes you marvel, reading it, at all the strange folds a single human brain can hold.

I told Murakami that I was surprised to discover, after so many surprising books, that he managed to surprise me again. As usual, he took no credit, claiming to be just a boring old vessel for his imagination.

“The Little People came suddenly,” he said. “I don’t know who they are. I don’t know what it means. I was a prisoner of the story. I had no choice. They came, and I described it. That is my work.”

I asked Murakami, whose work is so often dreamlike, if he himself has vivid dreams. He said he could never remember them — he wakes up and there’s just nothing. The only dream he remembers from the last couple of years, he said, is a recurring nightmare that sounds a lot like a Haruki Murakami story. In the dream, a shadowy, unknown figure is cooking him what he calls “weird food”: snake-meat tempura, caterpillar pie and (an instant classic of Japanese dream-cuisine) rice with tiny pandas in it. He doesn’t want to eat it, but in the dream world he feels compelled to. He wakes up just before he takes a bite.

On our second day together, Murakami and I climbed into the backseat of his car and took a ride to his seaside home. One of his assistants, a stylish woman slightly younger than Aomame, drove us over Tokyo on the actual elevated highway from which Aomame makes her fateful descent in “1Q84.” The car stereo was playing Bruce Springsteen’s version of “Old Dan Tucker,” a classic piece of darkly surrealist Americana. (“Old Dan Tucker was a fine old man/Washed his face in a frying pan/Combed his hair with a wagon wheel/And died with a toothache in his heel.”)

As we drove, Murakami pointed out the emergency pullouts he had in mind when he wrote that opening scene. (He was stuck here in traffic, he said, just like Aomame, when the idea struck him.) Then he undertook an existentially complicated task: he tried to pinpoint, very precisely, on the actual highway, the spot where the fictional Aomame would have climbed down into a new world. “She was going from Yoga to Shibuya,” he said, looking out the car window. “So it was probably right here.” Then he turned to me and added, as if to remind us both: “But it’s not real.” Still, he looked back through the window and continued as if he were describing something that had actually happened. “Yes,” he said, pointing. “This is where she went down.” We were passing a building called the Carrot Tower, not far from a skyscraper that looked as if it had giant screws sticking into it. Then Murakami turned back to me and added, as if the thought had just occurred to him again: “But it’s not real.”

Murakami’s fiction has a special way of leaking into reality. During my five days in Japan, I found that I was less comfortable in actual Tokyo than I was in Murakami’s Tokyo — the real city filtered through the imaginative lens of his books. I spent as much time in that world as possible. I went to a baseball game at Jingu Stadium — the site of Murakami’s epiphany — and stood high up in the frenzy of the bleachers, paying special attention every time someone hit a double. (The closest I got to my own epiphany was when I shot an edamame bean straight down my throat and almost choked.) I went for a long run on Murakami’s favorite Tokyo running route, the Jingu-Gaien, while listening to his favorite running music, the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” and Eric Clapton’s 2001 album “Reptile.” My hotel was near Shinjuku Station, the transportation hub around which “1Q84” pivots, and I drank coffee and ate curry at its characters’ favorite meeting place, the Nakamuraya cafe. I went to a Denny’s at midnight — the scene of the opening of Murakami’s novel “After Dark” — and eavesdropped on Tokyoites over French toast and bubble tea. I became hyperaware, as I wandered around, of the things Murakami novels are hyperaware of: incidental music, ascents and descents, the shapes of people’s ears.

In doing all of this I was joining a long line of Murakami pilgrims. People have published cookbooks based on the meals described in his novels and assembled endless online playlists of the music his characters listen to. Murakami told me, with obvious delight, that a company in Korea has organized “Kafka on the Shore” tour groups in Western Japan, and that his Polish translator is putting together a “1Q84”-themed travel guide to Tokyo.

Sometimes the tourism even crosses metaphysical boundaries. Murakami often hears from readers who have “discovered” his inventions in the real world: a restaurant or a shop that he thought he made up, they report, actually exists in Tokyo. In Sapporo, there are now apparently multiple Dolphin Hotels — an establishment Murakami invented in “A Wild Sheep Chase.” After publishing “1Q84,” Murakami received a letter from a family with the surname “Aomame,” a name so improbable (remember: “green peas”) he thought he invented it. He sent them a signed copy of the book. The kicker is that all of this — fiction leaking into reality, reality leaking into fiction — is what most of Murakami’s fiction (including, especially, “1Q84”) is all about. He is always shuttling us back and forth between worlds.

This calls to mind the act of translation — shuttling from one world to another — which is in many ways the key to understanding Murakami’s work. He has consistently denied being influenced by Japanese writers; he even spoke, early in his career, about escaping “the curse of Japanese.” Instead, he formed his literary sensibilities as a teenager by obsessively reading Western novelists: the classic Europeans (Dostoyevsky, Stendhal, Dickens) but especially a cluster of 20th-century Americans whom he has read over and over throughout his life — Raymond Chandler, Truman Capote, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Richard Brautigan, Kurt Vonnegut. When Murakami sat down to write his first novel, he struggled until he came up with an unorthodox solution: he wrote the book’s opening in English, then translated it back into Japanese. This, he says, is how he found his voice. Murakami’s longstanding translator, Jay Rubin, told me that a distinctive feature of Murakami’s Japanese is that it often reads, in the original, as if it has been translated from English.

You could even say that translation is the organizing principle of Murakami’s work: that his stories are not only translated but about translation. The signature pleasure of a Murakami plot is watching a very ordinary situation (riding an elevator, boiling spaghetti, ironing a shirt) turn suddenly extraordinary (a mysterious phone call, a trip down a magical well, a conversation with a Sheep Man) — watching a character, in other words, being dropped from a position of existential fluency into something completely foreign and then being forced to mediate, awkwardly, between those two realities. A Murakami character is always, in a sense, translating between radically different worlds: mundane and bizarre, natural and supernatural, country and city, male and female, overground and underground. His entire oeuvre, in other words, is the act of translation dramatized.

Back in the backseat of Murakami’s car, we left Tokyo and entered its exurbs. We passed numerous corporate headquarters, as well as a love hotel shaped like a giant boat. After an hour or so, the landscape thickened and rose, and we arrived at Murakami’s house, a nice but ordinary-looking two-story structure in a leafy, hilly neighborhood halfway between the mountains and the sea.

I exchanged my shoes for slippers, and Murakami took me upstairs to his office — the voluntary cell in which he wrote most of “1Q84.” This is also, not coincidentally, the home of his vast record collection. (He guesses that he has around 10,000 but says he’s too scared to count.) The office’s two long walls were covered from floor to ceiling with albums, all neatly shelved in plastic sleeves. Presiding over the end of the room, under a high bank of windows that looked out onto the mountains, were two huge stereo speakers. The room’s other shelves held mementos of Murakami’s life and work: a mug featuring Johnnie Walker, the whisky icon whom he re-imagined as a murderous villain in “Kafka on the Shore”; a photo of himself looking miserable while finishing his fastest marathon ever (1991, New York City, 3:31:27). On the walls were a photo of Raymond Carver, a poster of Glenn Gould and some small paintings of important jazz figures, including Murakami’s favorite musician of all time, the tenor saxophonist Stan Getz.

I asked if we could listen to a record, and Murakami put on Janacek’s “Sinfonietta,” the song that kicks off, and then periodically haunts, the narrative of “1Q84.” It is, as the book suggests, truly the worst possible music for a traffic jam: busy, upbeat, dramatic — like five normal songs fighting for supremacy inside an empty paint can. This makes it the perfect theme for the frantic, lumpy, violent adventure of “1Q84.” Shouting over the music, Murakami told me that he chose the “Sinfonietta” precisely for its weirdness. “Just once I heard that music in a concert hall,” he said. “There were 15 trumpeters behind the orchestra. Strange. Very strange. . . . And that weirdness fits very well in this book. I cannot imagine what other kind of music is fitting so well in this story.” He said he listened to the song, over and over, as he wrote the opening scene. “I chose the ‘Sinfonietta’ because that is not a popular music at all. But after I published this book, the music became popular in this country. . . . Mr. Seiji Ozawa thanked me. His record has sold well.”

When the “Sinfonietta” ended, I asked him if he could remember the first record he ever bought. He stood up, rummaged around one of his shelves and produced, for my inspection, “The Many Sides of Gene Pitney.” Its cover featured a glamour shot of Pitney, an early-’60s American crooner, wearing a spotted ascot and a lush red jacket. His hair looked like a cresting wave frozen into shape. Murakami said he bought the record in Kobe when he was 13. (This was a replacement copy; he wore the original out decades ago.) He dropped the needle and played Pitney’s first big hit, “Town Without Pity,” a dramatic, horn-filled vamp in which Pitney voices a young lover crooning an apocalyptic cry for help: “The young have problems, many problems/We need an understanding heart/Why don’t they help us, try to help us/Before this clay and granite planet falls apart?”

Murakami lifted the needle as soon as it was over. “A silly song,” he said.

The title of “1Q84” is a joke: an Orwell reference that hinges on a multilingual pun. (In Japanese, the number 9 is pronounced like the English letter Q.)

I asked Murakami if he reread “1984” while writing “1Q84.” He said he did, and it was boring. (Not that this is necessarily bad; at one point I asked him why he liked baseball. “Because it’s boring,” he said.)

“Most near-future fictions are boring,” he told me. “It’s always dark and always raining, and people are so unhappy. I like what Cormac McCarthy wrote, ‘The Road’ — it’s very well written. . . . But still it’s boring. It’s dark, and the people are eating people. . . . George Orwell’s ‘1984’ is near-future fiction, but this is near-past fiction,” he said of “1Q84.” “We are looking at the same year from the opposite side. If it’s near past, it’s not boring.”

I asked him if he felt any kinship with Orwell.

“I guess we have a common feeling against the system,” Murakami said. “George Orwell is half journalist, half fiction writer. I’m 100 percent fiction writer. . . . I don’t want to write messages. I want to write good stories. I think of myself as a political person, but I don’t state my political messages to anybody.”

And yet Murakami has, uncharacteristically, stated his political messages very loudly over the last couple of years. In 2009, he made a controversial visit to Israel to accept the prestigious Jerusalem Prize and used the occasion to speak out about Israel and Palestine. This summer, he used an awards ceremony in Barcelona as a platform to criticize Japan’s nuclear industry. He called Fukushima Daiichi the second nuclear disaster in the history of Japan, but the first that was entirely self-inflicted.

When I asked him about his Barcelona speech, he modified his percentages slightly.

“I am 99 percent a fiction writer and 1 percent a citizen,” he said. “As a citizen I have things to say, and when I have to do it, I do it clearly. At that point, nobody said no against nuclear-power plants. So I think I should do it. It’s my responsibility.” He said that the response to his speech, in Japan, was mostly positive — that people hoped, as he did, that the horror of the tsunami could be a catalyst for reform. “I think many Japanese people think this is a turning point for our country,” he said. “It was a nightmare, but still it’s a good chance to change. After 1945, we have been working so hard and getting rich. But that kind of thing doesn’t continue anymore. We have to change our values. We have to think about how we can get happy. It’s not about money. It’s not about efficiency. It’s about discipline and purpose. What I wanted to say is what I’ve been saying since 1968: we have to change the system. I think this is a time when we have to be idealistic again.”

I asked him what that idealism looked like, if he perhaps saw the United States as a model.

“I don’t think people think of America as a model anymore,” he said. “We don’t have any model at this moment. We have to establish the new model.”

The defining disasters of modern Japan — the subway sarin-gas attack, the Kobe earthquake, the recent tsunami — are, to an amazing extent, Murakami disasters: spasms of underground violence, deep unseen trauma that manifests itself as massive destruction to daily life on the surface. He is notoriously obsessed with metaphors of depth: characters climbing down empty wells to enter secret worlds or encountering dark creatures underneath Tokyo’s subway tunnels. (He once told an interviewer that he had to stop himself from using well imagery, after his eighth novel, because the frequency of it was starting to embarrass him.) He imagines his own creativity in terms of depth as well. Every morning at his desk, during his trance of total focus, Murakami becomes a Murakami character: an ordinary man who spelunks the caverns of his creative unconscious and faithfully reports what he finds.

“I live in Tokyo,” he told me, “a kind of civilized world — like New York or Los Angeles or London or Paris. If you want to find a magical situation, magical things, you have to go deep inside yourself. So that is what I do. People say it’s magic realism — but in the depths of my soul, it’s just realism. Not magical. While I’m writing, it’s very natural, very logical, very realistic and reasonable.”

Murakami insists that, when he’s not writing, he is an absolutely ordinary man — his creativity, he says, is a “black box” to which he has no conscious access. He tends to shy away from the media and is always surprised when a reader wants to shake his hand on the street. He says he much prefers to listen to other people talk — and indeed, he is known as a kind of Studs Terkel in Japan. After the 1995 sarin-gas attacks, Murakami spent a year interviewing 65 victims and perpetrators; he published the results in an enormous two-volume book, which was translated into English, heavily abridged, as “Underground.”

At the end of our time together, Murakami took me for a run. (“Most of what I know about writing,” he has written, “I’ve learned through running every day.”) His running style is an extension of his personality: easy, steady, matter of fact. After a minute or two, after we found our mutual stride, Murakami asked if I would like to start with something he referred to only as the Hill. The way he said it sounded like a challenge, a warning. Soon I understood his tone, because we were suddenly climbing it, the Hill — not exactly running anymore but stumbling in place at a serious tilt, the earth an angled treadmill underneath us. As we inched our way toward the end of the road, I turned to Murakami and said, “That was a big hill.” At which point he gestured to indicate that we had only reached the first of many switchbacks. After awhile, as our breathing turned more and more ragged, I started to wonder, pessimistically, if the switchbacks would never end, if we had entered some Murakami world of endless elevation: ascent, ascent, ascent. But then, finally, we reached the top. We could see the sea far below us: the vast secret water world, fully mapped but uninhabitable, stretching between Japan and America. Its surface looked calm, from where we stood, that day.

And then we started running down. Murakami led me through his village, past the surf shop on the main street, past a row of fishermen’s houses (he pointed out a traditional “fishermen’s shrine” in one of the yards). For a while the air was moist and salty as we ran parallel to the beach. We talked about John Irving, with whom Murakami once went jogging in Central Park as a young, unknown translator. We talked about cicadas: how strange it would be to live for so many years underground only to emerge, screaming, for a couple of fatal months up in the trees. Mainly I remember the steady rhythm of Murakami’s feet.

Back at the house, after our run, I showered and changed in Murakami’s guest bathroom. As I waited for him to come back downstairs, I stood in the breeze of the dining-room air-conditioner and looked out a picture window that framed a little backyard garden of herbs and small trees.

After a few minutes, a strange creature fluttered into my view of the garden. At first it seemed like some kind of bird — a strange hairy hummingbird, maybe, based on the way it was hovering. But then it started to look more like two birds stuck together: it wobbled more than it flew, and it had all kinds of flaps and extra parts hanging off it. I decided, in the end, that it was a big, black butterfly, the strangest butterfly I had ever seen. It floated there, wiggling like an alien fish, just long enough for me to be confused — to try to resolve it, never quite successfully, into some familiar category of thing. And then it flew away, wiggling, off down the mountain toward the ocean, retracing, roughly, the route Murakami and I had taken on our run.

Moments after the butterfly left, Murakami came down the stairs and sat, quietly, at his dining-room table. I told him I had just seen the weirdest butterfly I had ever seen in my entire life. He took a drink from his plastic water bottle, then looked up at me. “There are many butterflies in Japan,” he said. “It is not strange to see a butterfly.”

David

USA

Calling him a "global imaginative force" is a nice way of saying he writes superficial American literature in Japanese. His writing is like fast food that makes you happy: nicely packaged, nicely advertised, in a flashy wrapper, a lot people like it, not a lot of care went into it, nor much thought, and it is not nutritious. His work is not in the Japanese tradition, and it is an embarrassment compared to Yasunari Kawabata, Soseki Natsume, Oe Kenzaburo. His work is a sign of Japan's descent into comic book characters ("Superfrog Saves Tokyo") and overall cultural failure. Murakami is not really a writer, and his answers to life's problems are sounding more and more fatuous. That tsunami story right after the disaster looked more like a marketing ploy than anything else. And about the tsunami he says, "we discovered hope." That is the comic book mentality, the weakness and the pandering that Murakami's work exudes. It is fast food for the mind, and good business.

Mark

Tucson

@David. That's ridiculous and you know it. Murakami had masterly--deftly--captured that intersection between two worlds that include the cultural worlds of Japan and the West. His work is not supposed to be "in the Japanese tradition": he has explicitly, on more occasions than one, explained this. His influence was more Chandler and Carver (what about them--are they "fast food for the mind"?). As a translator, I also admire the sheer accomplishment of his translators; the stories, even in English, are riveting and entertaining--and like Isak Dinesen's work, they require readers to surrender to them and to the worlds their author constructs. Murakami deserves the Nobel Prize.

Axel

AK

Reflecting on Murakami’s writing, it strikes me that he may share more than a name with painter Takashi Murakami and his “superflat” paintings. Both employ tools and textures to create imagery that on the surface appears accessible to those not familiar with Japan’s cultural traditions (and, as some here have argued, lacks heft). Nevertheless, both seem to be looking inward rather than out, reinterpreting Buddhist perspectives as much reflecting on how Japanese society got to be where it is today. As pointed out in several posts, in the lesser work, texture can get in the way of content and superflat is just that. However, in their better work (such as Murakami’s short stories – A Shinagawa Monkey comes to mind) they are able to project the human, animal and inanimate world into a single plane in the best of Japanese Shinto and folk traditions. Without at least some insight into the latter (and despite all the references to western culture highlighted in this article), it may be as easy to get lost in their world as it is getting lost in Tokyo if all you have to go by is English signage.

Observer from the North

Montreal, Canada

I think the inner force moving Murakami to write may be compared the way of music is expressed in the absolute apparent dissonance and chaos which is Jazz. So it's not surprising that in his beginnings he was a truly amateur of jazz music. Whether musical jazz, that goes directly to our inner souls without distortions and sizes us with the pure joy of listening, can be translated in literature is a point not clear for me. The risk of becoming manga or (comics) is real. Time will tell us. It reminds me the beginning of the «magic realism» in Latin-america with Miguel Angel Asturias, García Márquez and also the poet Pablo Neruda, all of them Literature Nobel Prizes. But never in Latin America this literature would be compared to «comics», superficial writing void of content or pure fantasy.

While I liked the fine writing of Sam Anderson I cannot not smile at the pure american ingenuity expressed in his self description of something everybody outside U.S. knows about he typical American getting totally lost in any foreign country they go: not only they usually look like they do not to have the basis of the languages of those countries but any clue about their cultures.

Alex

Ithaca, NY

The comments display a concatenation of voices that are reminiscent of a Stravinsky symphony played after Mozart or Haydn. There are many problems with the review. The presentation of the Marakami phenomenon for American-Americans does seem directly compatible with the long-held Asian otherness that was initially derived from colonial gazetteers and memoirs of colonial officials and elites that became entrenched into the new field of anthropology. Post-colonial scholars would enjoy skewering the premises of this article. But aside from the alien otherness,Sam Anderson's ignorance of Japan and the Japanese language does seem congruent with an unsophisticated sense of infatuation and wonderment at the whimsical, bizarre and phantasmagoric worlds and mixed genres and playful weaving of themes “western” sprinkled with Buddhist and Japanese cultural references that are easily lost in even the best English translations. Over the years I think Murakami has developed an infatuation with high modernism (especially Proust) whose serious pretensions are deflated by an appreciation of Cheever and Carver and even Philip K. Dick in some places.

Part of the issue that the fictional works of Murakami that are raised by his immense global popularity that appears rather cultish when compared with say Bernhard Schlink (author “The Reader”) or Michael Ondaatje(author of “The English Patient”). This is because Murakami’s novels don’t directly confront the ethical dilemmas of self-identity and moral obligation, cosmopolitanism and hybridity as much as creative layered transcendental/mystical worlds that blur the boundaries between what we may call “dream-time” and the plurality of and near-simultaneity of worlds where boundaries of persons and objects, time and narrative become blended in a way that captures our current historical moment? Will Murakami and graphic novels and fantasy works supplant high-brow novels that can also be entertaining? That is a question we need to ask.

|

| Takashi Murakami |

"Don't think too hard about this stuff. This is the magnificent world of a picaresque novel"

By Shashank Singh

The above is a quote from this book, and well worth taking to heart. I take Jung's advice on dream images when reading a Murakami novel: don't try to unravel the underlying/hidden meaning, just stay with the images and let them move you and revel their meaning/feeling slowly.

There are images in this novel that will stay with me for years.

I'm a big fan and this is certainly one of his best novels, right there with works like The Wind Up Bird Chronicle, Norwegian Wood, and Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. Like all those works, reading the novel felt like slowly sinking into a well of dreams, and being enveloped in a mood of curiosity and off hand beauty/absurdity.

Some of the early reviews seem to be complaining about the book being repetitious, and the characters being too passive. All I can say is, this must be the first Murakami books you've read. This describes many of his books.

The passivity of the characters is actually essential to this book which deals with a world bereft of meaningful stories, and people susceptible to meaning that gives the false impression of depth [cults in this case].

Repetition is a form of making real in Murakami. The meanings are in the images, the images often begin as shadows, the novel takes those shadows and through echoes like a jazz song it breaths life into them: sometimes quite literally as in his book Hard Boiled Wonderland. I love it, but someone not used to it might find it odd.

As far as the more fantastic elements, I'll let Murakami speak for himself:

"I don't want to persuade the reader that it's a real thing; I want to show it as it is. In a sense, I'm telling those readers that it's just a story--it's fake. But when you experience the fake as real, it can be real. It's not easy to explain.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, writers offered the real thing; that was their task. In War and Peace Tolstoy describes the battleground so closely that the readers believe it's the real thing. But I don't. I'm not pretending it's the real thing. We are living in a fake world; we are watching fake evening news. We are fighting a fake war. Our government is fake. But we find reality in this fake world. So our stories are the same; we are walking through fake scenes, but ourselves, as we walk through these scenes, are real. The situation is real, in the sense that it's a commitment, it's a true relationship. That's what I want to write about." - 2004

To me this captures what I resonate with in Murakami's fiction: finding reality in simple things[cooking, having a bear, off hand conversations, relationships, music, art, thinking] in a world that is surreal or hyperreal much of the time. Even the surreal when followed deeper always leads to more reality not less in Murakami, you just can't cop out along the way, like how so many other postmodern writers do, you got to go deep into the well to use a often repeated Murakami image.

So overall, if you enjoy his works like me, this is a must read and a good time : If you've never read him, you might want to start with something shorter[I'd recommend Hard boiled wonderland].

P.S. The initial review was based on the first two books[UK edition], and now just having finished the third part [US edition] I can honestly say I felt satisfied with the ending. Murakami is very hit and miss with endings in my book, but this one worked for me. Also there are some great secondary characters here, my favorite overall might well be the private detective who shows up more prominently in the third book.

concerned reader

A real disappointment. It's a very long book but the story in no way justifies its 900+ pages, particularly the last 200 which are a tedious slog. All the trademark Murakami strokes and tropes are here in spades--the overall shimmering/fata morgana weirdness that leaves the reader a little dizzy and gravity-less time and again. Mundane descriptions of people, places, and situations that from one moment to the next morph into things eerie, half-funny/half- ominous, sometimes miraculous. And as usual at the center is a slightly befuddled, directionless protagonist expertly cooking his lonely guy meals while listening to classical music. Predictably he is unwillingly swept up by a series of events that, like a tornado, throws his life and future into chaos. Also there's a mysterious woman with beautiful ears, a number of enigmatic dream sequences that are sometimes resolved but usually aren't... All familiar, frequently delightful stuff for Murakami readers. In small doses. But the novel is simply too long for the tale it tells; it should have been cut by many pages. I started reading with enthusiasm and high expectations because it's this sui generis author and his purported magnum opus. But after turning the last page I felt relieved, exhausted and shrug'y. A friend and rabid Murakami fan who read 1Q84 at the same time I did said, `I'm going to need drugs to finish this damned book.'

FredrickJohnson

Santa Clara, CA

I think this "discussion" is fantastic. I am on the side of viewing Murakami's work as "as superficial as it is entertaining." I enjoyed The Wind-Up Bird, etc. quite a bit, but it struck me as a little flat - creative, colorful, with great moments - but with no real soul behind it.

On a separate topic, I disagree that he is NOT consistent with the Japanese tradition. In many ways, his work has the rhythm of the older Murakami. This comparison lends some support to my "superficial" critique as the older Murakami has all the grace and rhythm with the additional dimensions of music and poetry. In terms of the younger's congruence with contemporary Japanese culture, he fits perfectly with Japanese manga and film.

If you want depth, look to Korean film and working class Chinese writers.

Early in Haruki Murakami’s new novel, a character describes to an editor at a Japanese publishing house a manuscript of a novel that has come to his attention, and what he says sounds like a preview of the book we are about to read:

You could pick it apart completely if you wanted to. But the story itself has real power: it draws you in. The overall plot is a fantasy, but the descriptive detail is incredibly real. The balance between the two is excellent. I don’t know if words like “originality” or “inevitability” fit here, and I suppose I might agree if someone insisted it’s not at that level, but finally, after you work your way through the thing, with all its faults, it leaves a real impression—it gets to you in some strange, inexplicable way that may be a little disturbing.

After arriving at page 925 of 1Q84, the reader is likely to see an analogue. In this book, Murakami, who is nothing if not ambitious, has created a kind of alternative world, a mirror of ours, reversed. Even the book’s design emphasizes that mirroring: as you turn the pages, the page numbers climb or drop in succession along the margins, with the sequential numerals on one side in normal display type but mirror-reversed on the facing page. At one point, a character argues against the existence of a parallel world, but the two main characters in 1Q84 (Q=”a world that bears a question”) are absolutely convinced that they live not in a parallel world but in a replica one, where they do not want to be. The world we had is gone, and all we have now is a simulacrum, a fake, of the world we once had. “At some point in time,” a character muses, “the world I knew either vanished or withdrew, and another world came to take its place.”

This idea, which used to be the province of science fiction and French critical theory, is now in the mainstream, and it has created a new mode of fiction—Jonathan Lethem’s Chronic City is another recent example—that I would call “Unrealism.” Unrealism reflects an entire generation’s conviction that the world they have inherited is a crummy second-rate duplicate.

The word “realism” is a key descriptive term that readers often apply to certain works of literature without any general agreement about what it actually means. After all, if we cannot agree about what reality is, then why should we agree about what realism is, either? The entire topic dissolves quickly because its scope becomes too large and its outlines too indefinable to be particularly useful. Much of the time, we can talk about fiction without having to take a stand on what is real and what isn’t, although we do sometimes say that this or that event or character is “implausible” or “fantastical,” thereby rescuing truth-value for the plausible and the everyday.

Murakami’s novels, stories, and nonfiction refuse to make such distinctions, or, rather, they display, often very bravely and beautifully, the pull of the unreal and the fantastical on ordinary citizens who, unable to bear the world they have been given, desperately wish to go somewhere else. The resulting narratives conform to what I have called Unrealism. In Unrealism, characters join cults. They believe in the apocalypse and Armageddon, or they go down various rabbit holes and arrive in what Murakami himself, in a bow to Lewis Carroll, calls Wonderland. They long for the end times. Magical thinking dominates. Not everyone wants to be in such a dislocated locale, and the novels are often about heroic efforts to get out of Wonderland, but it is a primary destination site, like Las Vegas. As one character in 1Q84 says, “Everybody needs some kind of fantasy to go on living, don’t you think?”

1Q84 is a vast narrative inquiry into the fantasies that bind its dramatis personae to this world and the ones that loosen them from it. At its center are two characters—a young man, Tengo, a would-be novelist who by day teaches mathematics at a Tokyo cram school; and a young woman, Aomame (“green peas” in Japanese), a physical trainer and specialist in deep-tissue massage who is also a part-time assassin. We learn that at the age of ten the two of them met in grade school and joined hands and fell in love, and though they were separated soon after, they have somehow managed to continue to love each other, at a distance and sight unseen, over the course of two decades. The novel tracks their gradual coming together through a maze of trials in which monsters and devils figure prominently. This romance is at the core of the novel, as if Murakami had somehow hybridized The Magic Flute and Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, with a touch of Rosemary’s Baby thrown in for good measure.

The other really inescapable presence behind 1Q84 is George Orwell’s dystopia. The novel’s events occur in 1984, but instead of a Stalinist police state where the clocks strike thirteen, Murakami conjures up a cult, Sakigake (or “Forerunner”), with a charismatic leader, Tamotsu Fukada, along with a legion of mesmerized followers. Tengo and Aomame fall out of the ordinary world into a counterworld, 1Q84, shadowed everywhere by Sakigake and its goons. Although religious cultism has taken the place of political cultism, the effects here are remarkably similar. Within the Sakigake organization are thuggish enforcers and various forms of thought control. As if that weren’t enough, Sakigake has uncanny dark powers under its command that threaten the novel’s heroes and keep them in hiding, allowing the author to deploy various elements of the demonic. Just when you thought demons had been banished from serious fiction, Murakami has figured out a way to get them back in again.

“Their world,” one character notes, speaking of the Takashima Academy where the young Fukada, also known simply as “Leader,” went after having dropped out of a university, “is like the one that George Orwell depicted in his novel.”

I’m sure you realize that there are plenty of people who are looking for exactly that kind of brain death. It makes life a lot easier. You don’t have to think about difficult things, just shut up and do what your superiors tell you to do.

The landscape of 1Q84 is made even more complicated by the details of the alternative reality into which its two main characters have stumbled, mostly by accident. In this particular Wonderland, surveillance is everywhere; the innocent must hide; torture goes on in secret places; thugs rule. Who is to say that this unrealism isn’t true-to-life? Creating such Wonderlands is almost a thematic tic with Murakami: the protagonist of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, for example, finds his at the bottom of a dry well. Murakami himself is quite conscious of this habitual turn of his imagination. In his book on the gas attack in the Tokyo subway he writes:

Underground settings play particularly major roles in two of my novels,Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World and The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Characters go into the World Below in search of something and down there different adventures unfold. They head underground, of course, both in the physical and spiritual sense.1

The geography of 1Q84‘s Wonderland comprises Tokyo and its outskirts, along with recognizable cultural artifacts from the present and the past. The two main characters are ushered into it to the strains of Janáček’s Sinfonietta. But the locale also includes two moons, miniature angels or demons (it is hard to tell which they are) referred to as “Little People,” ghosts knocking on the door demanding payment, insemination-by-proxy, and air chrysalises: cocoons created by the Little People in which pod-like human replicas, referred to as dohta, are hatched. 1Q84is a marathon novel. (Murakami himself is a marathon runner and has said that “most of what I know about writing I’ve learned through running every day.”2) The experience of reading this book is anything but a long-distance trial, however. For most of its length, 1Q84 is a weirdly gripping page-turner, and its tonal register—as if serving as an antidote to the unsettling world it presents—is consistently warmhearted, secretly romantic, and really quite genial.

In 1Q84 the point of view alternates between Aomame and Tengo until a pathetic monster, Ushikawa, enters the book and, two thirds of the way through, gets his own narrative. The chapters from his point of view are both creepy and haunting.

In the first chapter of the book, on her way to an assassination, Aomame finds herself in a taxi trapped in a Tokyo traffic jam on an elevated freeway. Getting out of the cab, she walks over to an exit underneath an Esso gasoline billboard. Having been warned by the cab driver that “things are not what they seem,” she takes an emergency stairway from the exit downward to ground level where she slips through an opening in a fence. Any experienced reader of Murakami’s novels knows that from here on out, she’s in for it. Soon enough she recognizes that “the world itself has already changed into something else.”

The men Aomame periodically assassinates with an icepick are sadistically abusive, and we are to understand that in some sense she serves as an agent of divine justice. Sexual assaults recur throughout the novel, shadowing both the male and female characters; these assaults serve as the novel’s base line of depravity. Such depravity is countered by true love, which both Aomame and the novel believe in, or at least remember—in her case, with Tengo. By various twists and turns enabled by a patron usually referred to as “the dowager” and the dowager’s murderous gay bodyguard—a very lively character, by the way—Aomame eventually gains entry to the Leader’s presence, under the pretext of giving him a therapeutic session of stretching exercises to relax his musculature. The dowager has previously informed Aomame that the Leader has been having intercourse with preadolescent girls and is therefore worthy of execution, and her actual mission is to kill him. Here at the dead center of his novel, in a dialogue between Aomame and the Leader, Murakami gives us, for several chapters, a twenty-first century updated version of Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor scene—a debate, that is, on the nature of the sacred.

Meanwhile, the other hero of the novel, Tengo, has taken on the task of anonymously revising a novel, Air Chrysalis, dictated by a young woman, Eriko Fukada, called “Fuka-Eri” throughout. Her novel at first seems to be a farrago of Jungian archetypes and fairy tales, but once you get to the bottom of it, you find doubles, mazas and dohtas as they are called, “receivers” and “perceivers,” in a veiled allegory of her upbringing. The novel becomes a huge best seller, and Tengo finds himself in trouble for having collaborated with Fuka-Eri in giving away the esoteric truths and holy mysteries of Sagikake that make up the core of her tale.

Fuka-Eri, it turns out, is the Leader’s daughter, or the daughter’s replicant or near double, and as a replicant she has several zombie features, including affectlessness, the inability to use rising inflections for questions, and the capacity to quote long passages of literature (which she may not comprehend) from memory. So: at the same time that Aomame is putting herself in jeopardy with her mission to kill the Leader, Tengo is finding himself equally endangered, simply for having ghostwritten a book. They both go into hiding, at which point the hideously repulsive hired gumshoe Ushikawa, who is working for Sagikake, begins to track them down.

If my summary seems to suggest that some elements in 1Q84 are trashy, so be it. Murakami is a great democrat when it comes to subject matter and plot development. Digressions on the St. Matthew Passion, The Brothers Karamazov, and Chekhov’s book on Sakhalin vie for air time with observations on, and citations from, Sonny and Cher and Harold Arlen. Despite its various digressions, however, all roads in 1Q84 lead back to the Leader’s cult. The cult serves as the source, the electrical generator, of Wonderland and its spectacles, and cultism has the book’s imagination tightly in its grip. Sagikake in effect converts the world Tengo and Aomame live in from 1984 to 1Q84. Cultism rules this world. Only love can defeat it. In this sense the book’s redemptive structure could not be more traditional.

The shadow of the Aum Shinrikyo cult’s attack using sarin gas on the Tokyo subway on March 20, 1995, floats over the entire enterprise the way the apocalyptic violence of September 11 has floated over much recent American fiction. Murakami conducted extensive interviews with the victims and perpetrators of the Tokyo sarin attack and has published their comments along with his own thoughts on the matter in his nonfiction book Underground, published in the US in 2000.

In the afterword to that book, he argues that the Aum cult arose for several reasons: “in Aum they found a purity of purpose they could not find in ordinary society,” and, more tellingly, the cultists lacked “a broad world vision,” with the consequence that they experienced “the alienation between language and action that results from this.” In effect, they suffered from Unrealism and from the dark powers that arise from it: “language and logic cut off from reality have a far greater power than the language and logic of reality—with all that extraneous matter weighing down like a rock on any actions we take.” The “logic of reality”? We must acknowledge that Murakami accepts the existence of such logic and of a reality that cannot be altered by someone’s hallucinatory denial of it. But he doesn’t just accept it; he believes in it.

In case anyone thought that the psychic extremity leading to Aum was strictly Japanese, Murakami reminds us that Aum’s ambitions were similar to Ted Kaczynski’s. He also argues that “the argument Kaczynski puts forward is fundamentally quite right.”3

What’s fascinating about 1Q84 is its ambivalence about “the logic of reality” and its wish to plunge the reader into the “far greater power” of Unreality’s unlogic, which has the advantage of revolutionary fervor and reformism. Unrealism rejects what we have, or what the newspapers say we have, as uncongenial and loathsome and unsustainable, and offers up its own alternative. Within the subcultures it creates, almost all questions are answered. Fantasies are enacted. Beauty is reinstalled as a category. Everyday objects take on magical properties and serve as fetishes. Fiction, as Murakami knows perfectly well, can and does serve as a mirror world itself. It can both evoke Unrealism and collaborate with it, or it may deny it entirely. Fiction, then, can serve as both the poison and its antidote, though it is not scrupulously clear in 1Q84 whether Fuka-Eri’s novel Air Chrysalis has functioned as a cultural antitoxin or a hallucinogenic. Are novels good or bad for us? Tengo himself is not sure. Perhaps it is the wrong question.

The rogue power of Unrealism finds itself evoked in the chapters devoted to the dialogues between Aomame and the Leader, who sometimes sounds like Sarastro in The Magic Flute—a sorcerer who is suffering and wise and extremely dangerous. He can cause objects to levitate. He hears voices and transmits them to others. He is capable of causing paralysis in those close to him. He can read thoughts. He has read The Brothers Karamazov and The Golden Bough and can provide learned commentary on both. In short, he is not a monster; monsters work for him. As a figure of ambiguous purpose, he also promises Aomame that he will save Tengo’s life if only she carries out her assigned task. The Leader says that he himself must be killed. Speaking to his personal assassin in order to persuade her to do her job, the Leader launches into a lecture on anthropology out of Sir James Frazer:

Now, why did the king have to be killed? It was because in those days the king was the one who listened to the voices, as the representative of the people. Such a person would take it upon himself to become the circuit connecting “us” with “them.” And slaughtering the one who listened to the voices was the indispensible task of the community in order to maintain a balance between the minds of those who lived on the earth and the power manifested by the Little People.

The reader will note that the Leader’s explanation lets himself off the hook ethically for who he is and what he does. He isn’t quite responsible for his actions, nor are his followers. He is simply listening to the voices and passing on what the voices say to those who believe in him. He serves as a transmitting station of mythic patterns and extrasensory truth. If he dies, the “Little People would lose one who listens to their voices.”

And who are the Little People? The Little People, it appears, are unsignified signifiers. Almost everything in 1Q84, the book and the mirror world it creates, depends on their identity and their actions. If there is anything wrong with Murakami’s novel, it has to do with these figures, on whom the meanings of the counterworld absolutely depend and who are absolutely mystifying. It is as if the Seven Dwarfs had gradually made their presence known and their powers understood in a novel by James T. Farrell. What are we to make of them? Or of the hybrid novel in which they appear? Such are the perplexities, pleasures, and revelations of Unrealism.

The author himself seems somewhat undecided about who these creatures are—that is, what his imagination has created. Artists don’t need fully to understand their own art, but as the reader proceeds through Murakami’s novel, the suspicion grows that the author is riding a horse so powerful that it is occasionally not under his command and control. The horse is world-class and beautiful and fast, and the ride is thrilling. But the core meaning of what’s happening on the darker side of the spectrum has intermittently slipped away. The creation of the mirror world is essentially the doing of the Little People, but the Little People are accountable to nobody, and no one knows who or what they are.

Here is Murakami in an interview:

The Little People came suddenly. I don’t know who they are. I don’t know what it means. I was a prisoner of the story. I had no choice. They came, and I described it. That is my work.4

Fair enough. We have seen characters like this before in Murakami. They reminded me of the “TV People” in a story of that name in his collection The Elephant Vanishes, little goblin-like figures who look “as if they were reduced by photocopy, everything mechanically calibrated.”5 They come into your house without ringing the doorbell and they plant a TV in your living room. It’s just the sort of thing monsters do. “They just sneak right in. I don’t even hear a footstep. One opens the door, the other two carry in a TV.” Horror in Murakami’s fiction is often close to laughter, and both the TV People and the Little People possess a kind of comic unreadability.

As if to compensate for the Little People’s enigmatic existence and behavior, we are given in the last third of 1Q84 a recognizable monster, Ushikawa, the appallingly ugly outcast who listens to the Sibelius Violin Concerto while soaking in the bathtub. People cringe at his approach. Even his children avoid him. An entertainingly satanic figure, he sees it all; nothing escapes him, especially his own repulsiveness. “He felt like a twisted, ugly person. So what? he thought. I really am twisted and ugly.” He serves as the novel’s diabolical antagonist, the enemy of love between Tengo and Aomame, and he is quite wonderful to contemplate, up to and including the unforgettable scene in which he meets his nemesis, the dowager’s murderous gay bodyguard.

The whole of 1Q84 is closer to comedy than to tragedy, but it is a deeply obsessive book, and one of its obsessions is Macbeth and the problem of undoings. After saying that Banquo is dead and cannot come out of his grave, Lady Macbeth in Act Five observes that “what’s done cannot be undone.” Then she leaves the stage for the last time. What the two major characters in 1Q84desire above all else is to undo Wonderland and to get out of it and back to each other, but “gears that have turned forward never turn back,” a phrase that is repeated with variations three times in the novel, as if the problem of a snowball narrative had to do with how to melt the snowball and escape the glittering and thrilling world that Unrealism has created. 1Q84 seems to be about the undoing of a curse, so that the characters who believe that “the original world no longer exists” can somehow get back to that original world they no longer believe in. In a somewhat startling form of humanism and faith, Tengo and Aomame come to believe that what has been done can be undone.

That they do so by means of loyalty, prayers, and love is the most touching element of this book, and for some readers it will be the most questionable. Aomame, the novel’s assassin, repeats to herself a prayer that Murakami quotes several times. This prayer is the novel’s purest article of faith:

O Lord in Heaven, may Thy name be praised in utmost purity for ever and ever, and may Thy kingdom come to us. Please forgive our many sins, and bestow Thy blessings upon our humble pathways. Amen.

I finished 1Q84 feeling that its spiritual project was heroic and beautiful, that its central conflict involved a pitched battle between realism and unrealism (while being scrupulously fair to both sides), and that, in our own somewhat unreal times, younger readers, unlike me, would have no trouble at all believing in the existence of Little People and replicants. What they may have trouble with is the novel’s absolute faith in the transformative power of love.

- 1Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche , translated by Alfred Birnbaum and Philip Gabriel (Vintage, 2000), p. 240. ↩

- 2What I Talk About When I Talk About Running: A Memoir , translated by Philip Gabriel (Knopf, 2008), pp. 81–82. ↩

- 3In America, Chuck Klosterman's essay "Fail" in Eating the Dinosaur (Scribner, 2009) offers sympathy for Kaczynski on similar grounds ↩

- 4Sam Anderson, "The Fierce Imagination of Haruki Murakami," The New York Times Magazine , October 21, 2011. ↩

- 5The Elephant Vanishes , translated by Alfred Birnbaum and Jay Rubin (Knopf, 1993), p. 197. ↩

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu